ARKANSAS BLACK HISTORY // Building

Thomas C. McRae Sanatorium

Arkansas' First Treatment Facility for Black Victims of Tuberculosis

by Dianna Donahue - Jun.01.2021

Thomas C. McRae Sanatorium -- source: Historical Research Center, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

Thomas C. McRae Sanatorium -- source: Historical Research Center, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

Arkansas’ history tells of many practices used to uphold racial segregation in public facilities. Medical facilities were no exception to this neglectful discrimination. Depending on the town, Black medical facilities were not created with the same quality, accessibility, or efficiency compared to those created for white people – if they were created at all.

As tuberculosis spread throughout the United States towards the end of the 19th century, hundreds contracted or died from the disease daily. It was the second-leading cause of death in America, with a rate three times higher among Black people than white people. Similar stats posed true for Arkansas because its medical facilities were segregated, with only a few resources available to care for Black Arkansans.

The void of medical resources to Black tuberculosis victims was significantly due to a racially discriminatory theory that the biology of Black people made them more susceptible to contracting and inevitably dying from the disease. However, as the disease spread, white communities grew concerned for their health, being that many Black people worked in white communities. As the concern grew, decision-makers created measures to combat the disease in the form of segregated sanatoriums.

As tuberculosis spread throughout the United States towards the end of the 19th century, hundreds contracted or died from the disease daily. It was the second-leading cause of death in America, with a rate three times higher among Black people than white people. Similar stats posed true for Arkansas because its medical facilities were segregated, with only a few resources available to care for Black Arkansans.

The void of medical resources to Black tuberculosis victims was significantly due to a racially discriminatory theory that the biology of Black people made them more susceptible to contracting and inevitably dying from the disease. However, as the disease spread, white communities grew concerned for their health, being that many Black people worked in white communities. As the concern grew, decision-makers created measures to combat the disease in the form of segregated sanatoriums.

BLACK BIOLOGY

Dr. Edward Osgood Otis, a leading national authority on tuberculosis(1), believed the disease did not afflict all races the same. He argued that Black people contracted and died from tuberculosis at a higher rate because they weren’t slaves anymore. He believed “the colored race in the United States has at the present time at least four times mortality as the white race, whereas before the Civil War the disease was rare among the colored population” (Otis 19). In his opinion, because Black people were living as free citizens in a modern and civilized society, this made them more prone to contract tuberculosis. He believed that if Black people were still slaves, their consumption rate would not be so high.

It was a standard medical practice to perceive the body of a Black person as less developed and inherently degenerative than that of a white person. Many white physicians believed Black people’s biology – the size of the chest and the broadness of nostrils, for example – were defects and made them more vulnerable to contracting and dying from tuberculosis than white people.

These theories, and others like them, permeated the medical disposition of the South and affected how white physicians treated Black patients. Often time, white physicians blamed their racial irresponsibility on the biological design of Black people. Black cases of tuberculosis were often automatically given a prognosis of death with no attempt to offer aid. It was the blanketed opinion of many policymakers that it would be wasteful to create financial, medical, and educational resources for Black people with tuberculosis because they were unavoidably going to die from the disease anyway. The opinion of wasted resources also affected the urgency to create healthcare facilities.

Many of these opinions and theories were manipulative tactics for segregation and the entitlement nature of many white people to preserve Jim Crow. Nonetheless, the disease was a threat in Arkansas, so legislatures positioned the state to use quarantining to combat the disease – especially in favor of protecting white communities.

Dr. Edward Osgood Otis, a leading national authority on tuberculosis(1), believed the disease did not afflict all races the same. He argued that Black people contracted and died from tuberculosis at a higher rate because they weren’t slaves anymore. He believed “the colored race in the United States has at the present time at least four times mortality as the white race, whereas before the Civil War the disease was rare among the colored population” (Otis 19). In his opinion, because Black people were living as free citizens in a modern and civilized society, this made them more prone to contract tuberculosis. He believed that if Black people were still slaves, their consumption rate would not be so high.

It was a standard medical practice to perceive the body of a Black person as less developed and inherently degenerative than that of a white person. Many white physicians believed Black people’s biology – the size of the chest and the broadness of nostrils, for example – were defects and made them more vulnerable to contracting and dying from tuberculosis than white people.

These theories, and others like them, permeated the medical disposition of the South and affected how white physicians treated Black patients. Often time, white physicians blamed their racial irresponsibility on the biological design of Black people. Black cases of tuberculosis were often automatically given a prognosis of death with no attempt to offer aid. It was the blanketed opinion of many policymakers that it would be wasteful to create financial, medical, and educational resources for Black people with tuberculosis because they were unavoidably going to die from the disease anyway. The opinion of wasted resources also affected the urgency to create healthcare facilities.

Many of these opinions and theories were manipulative tactics for segregation and the entitlement nature of many white people to preserve Jim Crow. Nonetheless, the disease was a threat in Arkansas, so legislatures positioned the state to use quarantining to combat the disease – especially in favor of protecting white communities.

SANATORIUM

The National Tuberculosis Association was established in 1904, and the Arkansas Tuberculosis Association was founded in 1908 in Little Rock. The first facility for tuberculosis treatment was the Arkansas State Tuberculosis Sanatorium, founded in Booneville, Arkansas, in 1908. It was a ‘whites only’ facility, and its first patient was admitted in August of 1910.

During this time, the only resource available to Black tuberculosis-infected people was the ten beds offered at the Colored Cottage of the County Hospital. Governor Thomas C. McRae, a member of the Arkansas Tuberculosis Association, stated it was the “poorest of facilities.” It faced obstacles of funding, staffing, and resources – all needed to be an adequate facility. So, the association’s first objective became creating Black sanatoriums(2).

Miss Erle Chambers served as the Executive Secretary of the Arkansas Tuberculosis Association. Although she was a white woman, she had a great concern for the health of people, particularly the growing rate of deaths among Black people. In 1919, she took her concerns to the General Assembly, and Governor McRae passed a legislature to create a Black sanatorium in 1923. Although funding had not been allocated for a facility, McRae pressed forward establishing a board of trustees for it: Elizabeth Jordan of Brinkley, Mrs. S.T. Boyd of Prescott, and Dr. George William Stanley Ish, a noted Little Rock physician – all Black, and Miss Erle Chambers and State Senator Peter Deisch of Helena—both white.

Funding would not be allocated for the actual facility for another decade, but the board proceeded to locate a site in Alexander, Arkansas. While purchasing options were being discussed, Governor Tom Terrell dissolved the trustees’ board, causing the project to be delayed. However, Chicot County’s Harvey Parnell resurrected the project after he won the governorship in 1928. He established a new board of trustees, including Dr. Ish and Mrs. W. T. Dorough – a white woman (both of Little Rock) and several other Black members. Under their leadership, the legislature allocated $26,000 to construct a sanatorium, and the facility became operational by 1931. It was called the Thomas C. McRae Sanatorium for Negroes and had only twenty-six beds.

The National Tuberculosis Association was established in 1904, and the Arkansas Tuberculosis Association was founded in 1908 in Little Rock. The first facility for tuberculosis treatment was the Arkansas State Tuberculosis Sanatorium, founded in Booneville, Arkansas, in 1908. It was a ‘whites only’ facility, and its first patient was admitted in August of 1910.

During this time, the only resource available to Black tuberculosis-infected people was the ten beds offered at the Colored Cottage of the County Hospital. Governor Thomas C. McRae, a member of the Arkansas Tuberculosis Association, stated it was the “poorest of facilities.” It faced obstacles of funding, staffing, and resources – all needed to be an adequate facility. So, the association’s first objective became creating Black sanatoriums(2).

Miss Erle Chambers served as the Executive Secretary of the Arkansas Tuberculosis Association. Although she was a white woman, she had a great concern for the health of people, particularly the growing rate of deaths among Black people. In 1919, she took her concerns to the General Assembly, and Governor McRae passed a legislature to create a Black sanatorium in 1923. Although funding had not been allocated for a facility, McRae pressed forward establishing a board of trustees for it: Elizabeth Jordan of Brinkley, Mrs. S.T. Boyd of Prescott, and Dr. George William Stanley Ish, a noted Little Rock physician – all Black, and Miss Erle Chambers and State Senator Peter Deisch of Helena—both white.

Funding would not be allocated for the actual facility for another decade, but the board proceeded to locate a site in Alexander, Arkansas. While purchasing options were being discussed, Governor Tom Terrell dissolved the trustees’ board, causing the project to be delayed. However, Chicot County’s Harvey Parnell resurrected the project after he won the governorship in 1928. He established a new board of trustees, including Dr. Ish and Mrs. W. T. Dorough – a white woman (both of Little Rock) and several other Black members. Under their leadership, the legislature allocated $26,000 to construct a sanatorium, and the facility became operational by 1931. It was called the Thomas C. McRae Sanatorium for Negroes and had only twenty-six beds.

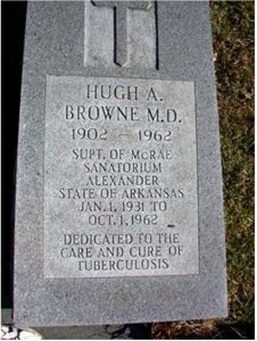

DR. HUGH A. BROWNE

With the facility complete, it needed a director for it to be operational. The board of trustees did not want to hire a white physician to oversee the ‘Blacks only’ facility, so it sought a Black physician. The board strongly considered Dr. Hugh A. Brown of Kansas City, Kansas. He was the son of a physician, a graduate of Howard University’s Medical Department, and a Kansas City physician with a lucrative practice. He was also the Chief Resident Doctor of the Wheatley-Provident Hospital and specialized in pulmonary diseases with emphasis on tuberculosis.

Dr. Browne developed an interest in tuberculosis after discovering that he had the disease during a routine high school physical examination. The white physician suggested Browne enjoyed the rest of his life with consumption, but Browne decided to learn everything he could about the disease. He spent much of his time resting and learning, and his lungs cleared after two years.

A $200 per month offer was made to Dr. Browne by the board, who made $1,500 monthly through his practice in Kansas. Dr. Browne promptly rejected the offer. However, in a turn of events, he had to stay in Little Rock overnight because of a travel delay. The Black Little Rock physician, Dr. Ish, seized the opportunity to have a one-on-one conversation with Dr. Browne. He accepted the offer the following day.

Dr. Browne developed an interest in tuberculosis after discovering that he had the disease during a routine high school physical examination. The white physician suggested Browne enjoyed the rest of his life with consumption, but Browne decided to learn everything he could about the disease. He spent much of his time resting and learning, and his lungs cleared after two years.

A $200 per month offer was made to Dr. Browne by the board, who made $1,500 monthly through his practice in Kansas. Dr. Browne promptly rejected the offer. However, in a turn of events, he had to stay in Little Rock overnight because of a travel delay. The Black Little Rock physician, Dr. Ish, seized the opportunity to have a one-on-one conversation with Dr. Browne. He accepted the offer the following day.

Dr. Browne moved his entire family into the facility for a time and received help from his wife, Norma J. Browne. She was his personal secretary, the Personnel Director, the Chief Administrative Assistant, and the Purchasing Agent. With the assistance of his two nurses, Dr. Browne worked diligently to help Black Arkansans with tuberculosis. His own experience and studies of tuberculosis enabled him to understand the disease and how to provide aid.

The facility’s waiting list grew into the hundreds within days of opening and stayed that way regularly. The workload often proved greater than his wife and staff could handle, so he constantly worked to find private funding and advocates from private auxiliaries, such as women of Black state medical societies and medical volunteers.

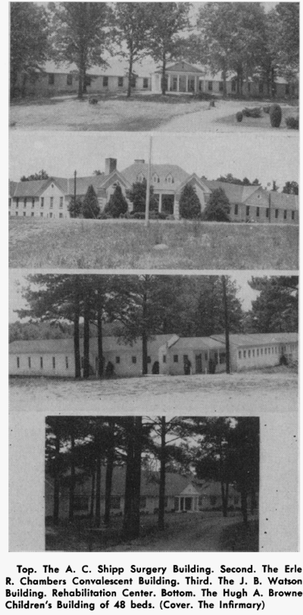

Dr. Browne wanted to expand the available services to his patients as he believed they should be treated for more than just tuberculosis. He wanted to offer extensive care services and educate them while they healed. He managed to attain funding from the Federal Works Progress Administration to build a new multipurpose building named for Miss Erle Chambers in 1935. It housed a modern surgical unit, dining facilities, and a crafting area. It was only one of several buildings erected through Dr. Browne’s leadership, including a children’s wing. He also created educational programs and vocational rehabilitation. These resources helped keep the hospital’s doors open when the legislature stopped contributing.

The facility’s waiting list grew into the hundreds within days of opening and stayed that way regularly. The workload often proved greater than his wife and staff could handle, so he constantly worked to find private funding and advocates from private auxiliaries, such as women of Black state medical societies and medical volunteers.

Dr. Browne wanted to expand the available services to his patients as he believed they should be treated for more than just tuberculosis. He wanted to offer extensive care services and educate them while they healed. He managed to attain funding from the Federal Works Progress Administration to build a new multipurpose building named for Miss Erle Chambers in 1935. It housed a modern surgical unit, dining facilities, and a crafting area. It was only one of several buildings erected through Dr. Browne’s leadership, including a children’s wing. He also created educational programs and vocational rehabilitation. These resources helped keep the hospital’s doors open when the legislature stopped contributing.

ACHIEVEMENTS

Thomas C. McRae Sanatorium was created with intentions to keep contagious Black people contained to preserve white communities. This intent was based on false medical theories of the Black biology created by white physicians to dismiss themselves from providing Blacks with adequate aid, perpetuating Jim Crow segregation preferences. Black patients fell victim to tuberculosis by the hundreds due to this neglect, leaving hundreds more to suffer and grieve.

In contrast to the intent, Dr. Browne achieved many successes for the sanatorium under his leadership, even with the lack of continued support from legislation. During his leadership, he was chosen to be the superintendent of the sanatorium - a rare position for a Black doctor. He had become a member of the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Thoracic Society, and the National Medical Association when he ended his career in medicine.

His commitment to the sanatorium culminated after 31 years, and he retired in 1962. Dr. Ish presented him with a certificate of recognition that included a growth of 411 beds from the original twenty-six, 390 patients, 146 employees, and more than 7,000 treated patients in the Thomas C. McRae Sanatorium for Negros.

In contrast to the intent, Dr. Browne achieved many successes for the sanatorium under his leadership, even with the lack of continued support from legislation. During his leadership, he was chosen to be the superintendent of the sanatorium - a rare position for a Black doctor. He had become a member of the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Thoracic Society, and the National Medical Association when he ended his career in medicine.

His commitment to the sanatorium culminated after 31 years, and he retired in 1962. Dr. Ish presented him with a certificate of recognition that included a growth of 411 beds from the original twenty-six, 390 patients, 146 employees, and more than 7,000 treated patients in the Thomas C. McRae Sanatorium for Negros.

A group of Thomas C. McRae Sanatorium nurse with Br. Browne (far right on second row)

A group of Thomas C. McRae Sanatorium nurse with Br. Browne (far right on second row)

The sanatorium became the Alexander Human Development Center in 1968 after the segregated facilities in the state merged. Under its new title, the facility offered: mentally disabled psychological assessments, rehabilitation services, general medical care, and three forms of therapy (occupational, speech, and physical) inclusive of the tuberculosis services it provided initially.

PRESENT DAY

The new facility operated for over forty years under the direction of the Arkansas Department of Human Services. Numerous complaints and allegations of neglect and rape of its patients began to surface, getting the attention of Governor Mike Beebe. Compounded by multiple failed inspections and the loss of its Medicaid certification, investigations resulted in the facility ceasing operations and closing its doors in 2011. As many as 109 men were residing at the facility at the time that it closed.

The Alexander Police Department eventually purchased the building in 2018 from a private owner. In March 2020, a fire broke out that required 17 surrounding fire departments to extinguish. Fire officials warned the community to stay away from the building because of the presence of asbestos. Today, the latest version of the facility sits abandoned, severely damaged, and gated up.

The new facility operated for over forty years under the direction of the Arkansas Department of Human Services. Numerous complaints and allegations of neglect and rape of its patients began to surface, getting the attention of Governor Mike Beebe. Compounded by multiple failed inspections and the loss of its Medicaid certification, investigations resulted in the facility ceasing operations and closing its doors in 2011. As many as 109 men were residing at the facility at the time that it closed.

The Alexander Police Department eventually purchased the building in 2018 from a private owner. In March 2020, a fire broke out that required 17 surrounding fire departments to extinguish. Fire officials warned the community to stay away from the building because of the presence of asbestos. Today, the latest version of the facility sits abandoned, severely damaged, and gated up.