ARKANSAS BLACK HISTORY // Entrepreneur

John H. Johnson

The Forbes 400 List's First Black Entrepreneur & Businessman

by Dianna Donahue - Nov.01.2021

If you grew up during the 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s, chances are you are familiar with publications such as Negro Digest, Ebony Magazine, or Jet Magazine. These publications were staples in most of our lives and primary sources of exposure to the multifaceted Black culture across the country. Although these publications have made decades of impact across the world, many of their readers are unaware that these are just a few publishing efforts successfully executed by Arkansas City’s own John Harold Johnson. He is the grandson of slaves and the founder of the Johnson Publishing Company – the United States’ largest Black-owned publishing business – which is still generationally empowering Black people worldwide.

On January 19, 1918, Johnny Johnson was born in Arkansas City – the Arkansas Delta – to Leroy and Gertrude Jenkins Johnson. His father was killed in a sawmill accident in 1924 when Johnny was six years old. He had a half-sister 14 years older than him named Beulah, his mother’s child from her previous marriage to Richard Lewis. After Johnny’s father died, his mother married James Williams, who helped raise Johnny in Arkansas City. The Great Flood of 1927 forced the three to live on the Mississippi River levee for six weeks before they were able to return to their home.

Johnny attended the town’s segregated elementary school through the eighth grade at the Arkansas City Colored School. His mother was very aware of the unlikelihood that her son would be educated beyond eighth grade in the Delta since there was no high school available to Black students. So she internally decided to move to Chicago, Illinois, immediately after his graduation. Unfortunately, she had not saved enough money by that time, so she made him repeat the 8th grade until she did.

The neighborhood, as well as her husband, were unsupportive of her decision. And although she loved her husband, she courageously acted upon her desire for her son to have freedom, education, and better opportunities. She left Arkansas City in 1933 with no intention of returning as a resident with her son in tow. Johnny was 15 years old.

Johnny attended the town’s segregated elementary school through the eighth grade at the Arkansas City Colored School. His mother was very aware of the unlikelihood that her son would be educated beyond eighth grade in the Delta since there was no high school available to Black students. So she internally decided to move to Chicago, Illinois, immediately after his graduation. Unfortunately, she had not saved enough money by that time, so she made him repeat the 8th grade until she did.

The neighborhood, as well as her husband, were unsupportive of her decision. And although she loved her husband, she courageously acted upon her desire for her son to have freedom, education, and better opportunities. She left Arkansas City in 1933 with no intention of returning as a resident with her son in tow. Johnny was 15 years old.

“ I was impressed by the steam heat and the inside toilet. ”

Gertrude Jenkins Johnson, Johnson's mother

Gertrude Jenkins Johnson, Johnson's mother

CHICAGO

Once he and his mother arrived in Chicago at the Illinois Central Station, Johnny stood transfixed on the street by the traffic, tall buildings, and sea of Black people. The mother and son took a taxi to 422 East Forty-fourth Street, where his mother’s friend, and immigrant from Arkansas City, Mamie Jonson, greeted them into a three-story building. She made a bedroom out of the third-floor attic for them – Mrs. Gertrude slept in the bed, and Johnny slept on a rollaway bed.

In the months that followed, Johnny was introduced to city life, academic opportunities, Black politics, Black politicians, Black businessmen, and Black middle-class. He was amazed and had no desire to return to the Delta, referring to Chicago as “my kind of town.”

Johnny’s half-sister moved to Chicago before he and Mrs. Gertrude, and the three moved into an apartment together shortly after the mother-son duo arrived with Johnny’s stepfather, eventually making the migration, as well. Unfortunately, the residuals of the Great Depression in Black America went from bad to worse on the heels of Mr. Williams’ arrival, and the family had to receive welfare from 1934 until 1936. Johnny was not proud of this and used it as a constant motivation to progress for the rest of his life.

He attended the New Wendell Phillips High School – a virtually all-Black school named after a white abolitionist – with a student population larger than the total population of Arkansas City. The name was later changed in 1936 to Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable High School after Chicago’s first permanent non-native settler.

Once he and his mother arrived in Chicago at the Illinois Central Station, Johnny stood transfixed on the street by the traffic, tall buildings, and sea of Black people. The mother and son took a taxi to 422 East Forty-fourth Street, where his mother’s friend, and immigrant from Arkansas City, Mamie Jonson, greeted them into a three-story building. She made a bedroom out of the third-floor attic for them – Mrs. Gertrude slept in the bed, and Johnny slept on a rollaway bed.

In the months that followed, Johnny was introduced to city life, academic opportunities, Black politics, Black politicians, Black businessmen, and Black middle-class. He was amazed and had no desire to return to the Delta, referring to Chicago as “my kind of town.”

Johnny’s half-sister moved to Chicago before he and Mrs. Gertrude, and the three moved into an apartment together shortly after the mother-son duo arrived with Johnny’s stepfather, eventually making the migration, as well. Unfortunately, the residuals of the Great Depression in Black America went from bad to worse on the heels of Mr. Williams’ arrival, and the family had to receive welfare from 1934 until 1936. Johnny was not proud of this and used it as a constant motivation to progress for the rest of his life.

He attended the New Wendell Phillips High School – a virtually all-Black school named after a white abolitionist – with a student population larger than the total population of Arkansas City. The name was later changed in 1936 to Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable High School after Chicago’s first permanent non-native settler.

Harry H. Pace

Harry H. Pace

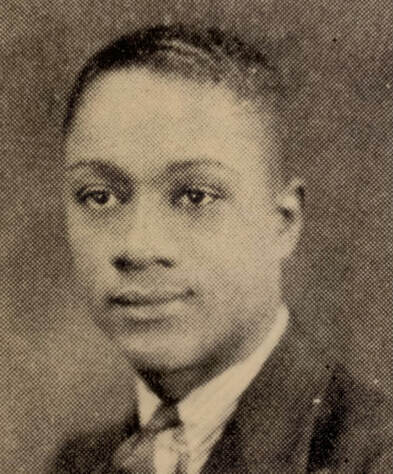

Johnny entered as a sophomore (skipping the ninth grade) and took a journalism course upon entry. He also worked on the school newspaper, eventually became the Editor in Chief, the Sales Manager of the school yearbook, was the class president, organized forums, mimeographed a magazine for the National Youth Administration called the Afri-American Youth, and became a young professional leader. At his 1936 high school graduation ceremony, a teacher suggested to Johnny that he adopt a more adult-sounding name. So Johnny Johnson shortened his first name, gave himself a middle name, and became John Harold Johnson.

Johnson graduated with honors, several recognitions, and even a small scholarship. Unsure how he would come up with additional money to pay the difference for a college education, Johnny decided to do nothing. He just kept going with his regular day-to-day life. One day he attended a routine Urban League Luncheon for outstanding high school students. The main speaker was Harry Herbert Pace – president of the Supreme Liberty Life Insurance Company, the largest Black business in the North, and one of John H. Johnson’s heroes.

After Pace finished, Johnson introduced himself and complimented Pace’s speech. Pace returned the compliment regarding the great things he’d heard about Johnson and asked him what he planned on doing with himself. Johnson expressed that he wanted to go to college but didn’t know how to pay for it. Pace told him that he might have part-time work for him that would allow him to work and go to college and to contact him on the first working day of September. Unbeknownst to Johnson, his future was sealed at that moment.

Johnson graduated with honors, several recognitions, and even a small scholarship. Unsure how he would come up with additional money to pay the difference for a college education, Johnny decided to do nothing. He just kept going with his regular day-to-day life. One day he attended a routine Urban League Luncheon for outstanding high school students. The main speaker was Harry Herbert Pace – president of the Supreme Liberty Life Insurance Company, the largest Black business in the North, and one of John H. Johnson’s heroes.

After Pace finished, Johnson introduced himself and complimented Pace’s speech. Pace returned the compliment regarding the great things he’d heard about Johnson and asked him what he planned on doing with himself. Johnson expressed that he wanted to go to college but didn’t know how to pay for it. Pace told him that he might have part-time work for him that would allow him to work and go to college and to contact him on the first working day of September. Unbeknownst to Johnson, his future was sealed at that moment.

REPOSITIONING

“ The president is expecting me. ”

Eighteen-year-old John H. Johnson walked into the Supreme Liberty Life Headquarters on September 1, 1936, and asked to see the company’s president, Harry H. Pace. Pace greeted Johnson, and although he really didn’t have anything for Johnson to do, he assigned him to an empty desk outside his door. After about four months of just sitting at the desk, never being called on, Johnson decided to sneak away and get a soda – the precise moment that Pace called on him.

When Johnson returned, Pace told him, “Young man, one thing you’ve got to learn. I’m paying you to sit at your desk, and you should stay there, even if I never call you.” Johnson was being paid twenty-five dollars a month and was able to attend the University of Chicago simultaneously. Considering the times, he could not afford to be fired, so he stayed put from that day on.

His position became more relevant to him as he became a student of Pace and the company. Preferring the on-the-job education he gained at Supreme Life, Johnson dropped out of school became devoted to Supreme Life full-time. He could not resist the value of entrepreneurship and the private enterprise-based curriculum he had daily access to.

“ The president is expecting me. ”

Eighteen-year-old John H. Johnson walked into the Supreme Liberty Life Headquarters on September 1, 1936, and asked to see the company’s president, Harry H. Pace. Pace greeted Johnson, and although he really didn’t have anything for Johnson to do, he assigned him to an empty desk outside his door. After about four months of just sitting at the desk, never being called on, Johnson decided to sneak away and get a soda – the precise moment that Pace called on him.

When Johnson returned, Pace told him, “Young man, one thing you’ve got to learn. I’m paying you to sit at your desk, and you should stay there, even if I never call you.” Johnson was being paid twenty-five dollars a month and was able to attend the University of Chicago simultaneously. Considering the times, he could not afford to be fired, so he stayed put from that day on.

His position became more relevant to him as he became a student of Pace and the company. Preferring the on-the-job education he gained at Supreme Life, Johnson dropped out of school became devoted to Supreme Life full-time. He could not resist the value of entrepreneurship and the private enterprise-based curriculum he had daily access to.

Johnson was assigned to the company’s monthly newspaper, The Guardian, first as the assistant to the editor, then assistant editor, and then the editor in 1939. Pace eventually connected Johnson to General Counsel Earl B. Dickerson – a significant component of change in the political identity of Black America. Johnson helped Dickerson campaign and win the race for alderman of Chicago’s second ward and was named his Political Secretary at twenty-one years old. Johnson was making approximately $100 a week between the two jobs by the end of the thirties.

In 1940, a friend of Johnson’s introduced him to Eunice Walker – a Talladega College student and a member of one of the first and respected Black families in the South. They dated for a year against the wishes of many close to Eunice. There were multiple attempts to convince her that she was wasting her time with Johnson because of his background. Nevertheless, the two married in Selma, Alabama, on June 21, 1941. They later adopted two children: a son, John Harold, Jr., and a daughter, Linda.

The world, including America, Black America, and Black Chicago, had changed around this time due to war, civil rights protests, racial tensions, fear, uncertainty, and disgruntled opinions of economic inequality vocalized across the country. The effects were felt at Supreme Life as the loyalty and regard towards Harry H. Pace from the staff was fading. Many Black Chicagoans thought it unfair that Pace made his wealth on Black dollars, but his life resided in white environments protected from racial discrimination because he was passing as a white man.

It was rumored that the staff planned to follow him home to his white neighborhood and make it known to his white neighbors that he was passing. The disheartened Pace became secretive and withdrawn from his company and positioned Johnson to be a liaison between him and Black news for the company’s digest. Johnson was becoming so inundated with information that he was regarded as the most knowledgeable person in Black Chicago.

Johnson soon realized he was sitting on a Black gold mine that he could develop into a Reader’s Digest for Black people. He believed many Black communities across the country needed information to be disseminated to them – news, thoughts, and recognition of Black Americans by Black Americans that could restore some element of hope and calm within Black communities. With all his experience with publications, his answer to this void was a magazine.

In 1940, a friend of Johnson’s introduced him to Eunice Walker – a Talladega College student and a member of one of the first and respected Black families in the South. They dated for a year against the wishes of many close to Eunice. There were multiple attempts to convince her that she was wasting her time with Johnson because of his background. Nevertheless, the two married in Selma, Alabama, on June 21, 1941. They later adopted two children: a son, John Harold, Jr., and a daughter, Linda.

The world, including America, Black America, and Black Chicago, had changed around this time due to war, civil rights protests, racial tensions, fear, uncertainty, and disgruntled opinions of economic inequality vocalized across the country. The effects were felt at Supreme Life as the loyalty and regard towards Harry H. Pace from the staff was fading. Many Black Chicagoans thought it unfair that Pace made his wealth on Black dollars, but his life resided in white environments protected from racial discrimination because he was passing as a white man.

It was rumored that the staff planned to follow him home to his white neighborhood and make it known to his white neighbors that he was passing. The disheartened Pace became secretive and withdrawn from his company and positioned Johnson to be a liaison between him and Black news for the company’s digest. Johnson was becoming so inundated with information that he was regarded as the most knowledgeable person in Black Chicago.

Johnson soon realized he was sitting on a Black gold mine that he could develop into a Reader’s Digest for Black people. He believed many Black communities across the country needed information to be disseminated to them – news, thoughts, and recognition of Black Americans by Black Americans that could restore some element of hope and calm within Black communities. With all his experience with publications, his answer to this void was a magazine.

“ When I had exhausted every avenue of support, I returned to Johnson Rule No. 1 – What can you do by yourself with what you have to get what you want? ”

SHIT DETAIL

Johnson’s job duties at Supreme Life included “shit detail.” These duties were those that were petty and menial and usually assigned to low-ranking, entry-level employees. For example, one of Johnson’s “shit detail” duties was running the Speedaumat machine, which kept track of insurance policy buyers’ names and addresses. Naturally, he did not like this duty; however, he did it, and he did it well. Then came the day that he saw a personal benefit for it – these insurance policy buyers could be the first subscribers of his magazine.

Johnson presented his idea to Pace and asked for permission to use the contacts from the machine. Pace granted permission stating, “Since you are running the machine anyway, there’s no reason why you can’t use it to mail the letters.” Johnson immediately had access to 20,000 potential customers, and he prepared his letter requesting their help – buy a $2 prepaid subscription for a new Black magazine that didn’t exist yet. His next obstacle was figuring out where he would get $500 to pay for postage to mail the letters.

He went to the First National Bank of Chicago for a $500 loan and was laughed at to his face – “Boy, we don’t make any loans to colored people.” Standing up within himself, Johnson swallowed his anger and asked the white man, “Who in this town will loan money to a colored person?” The man responded, “The only place I know is the Citizens Loan Corporation at Sixty-third and Cottage Grove.” Johnson then asked

could he tell that bank that the man had referred him there, and the man said “Of course” in a more respectful and mindful tone than his initial disrespectful response.

Citizens Loan Corporation affirmed what the previous bank told Johnson but missed the part that Johnson would need collateral on the $500 loan. He did not have anything that he could use, but his mother did – her new furniture. He asked her, and she was not supportive of his plans for the first time in his life.

Mrs. Gertrude had worked a long time to pay for her furniture and had no intentions of losing it. She did, however, want to be supportive of her son, so she told him, “I’ll just have to consult the Lord about this. It’s not a decision I can make by myself.” After about four days of praying and crying together, she believed the Lord wanted her to make the sacrifice, so she turned over the receipts on her furniture, and Johnson had a $500 check shortly after that. He sent out his letters that June, and as a result, approximately 3,000 people mailed in $2 towards Johnson’s vision. The next step was to make the magazine exist.

Johnson made many connections working for Supreme Life, three of which were vital to the magazine’s creation: Jay Jackson, an artist and cartoonist who provided the graphics; Ben Burns, a freelance writer who helped Johnson with writing content; and Earl Dickerson, who gave him an office space to work and his new company a place to exist. With these three things in place, along with him and his wife, Eunice, to make up the slack, everything was set except a printer and money to print.

For this, Johnson reached back to one of his “shit detail” job duties as the Multilith operator, which required Johnson to work closely with the Progress Printing Company to print Supreme Life’s printed materials. So when he went to Progress to make his print request on the basis of credit, he referred to it as a “we (him as an employee of Supreme Life)” effort. The printer assumed the magazine would be backed or was owned by Supreme Life and agreed with no apprehension of repayment. Thus, due to multiple “shit detail” job duties, the Negro Digest was published on November 1, 1942, under the Negro Digest Publishing Company.

Johnson worked for Supreme Life Insurance Company until he could no longer do as the demand of his new venture became his focus. He eventually acquired most of Supreme Life Insurance Company’s interest in 1974 and became its CEO shortly after.

Johnson’s job duties at Supreme Life included “shit detail.” These duties were those that were petty and menial and usually assigned to low-ranking, entry-level employees. For example, one of Johnson’s “shit detail” duties was running the Speedaumat machine, which kept track of insurance policy buyers’ names and addresses. Naturally, he did not like this duty; however, he did it, and he did it well. Then came the day that he saw a personal benefit for it – these insurance policy buyers could be the first subscribers of his magazine.

Johnson presented his idea to Pace and asked for permission to use the contacts from the machine. Pace granted permission stating, “Since you are running the machine anyway, there’s no reason why you can’t use it to mail the letters.” Johnson immediately had access to 20,000 potential customers, and he prepared his letter requesting their help – buy a $2 prepaid subscription for a new Black magazine that didn’t exist yet. His next obstacle was figuring out where he would get $500 to pay for postage to mail the letters.

He went to the First National Bank of Chicago for a $500 loan and was laughed at to his face – “Boy, we don’t make any loans to colored people.” Standing up within himself, Johnson swallowed his anger and asked the white man, “Who in this town will loan money to a colored person?” The man responded, “The only place I know is the Citizens Loan Corporation at Sixty-third and Cottage Grove.” Johnson then asked

could he tell that bank that the man had referred him there, and the man said “Of course” in a more respectful and mindful tone than his initial disrespectful response.

Citizens Loan Corporation affirmed what the previous bank told Johnson but missed the part that Johnson would need collateral on the $500 loan. He did not have anything that he could use, but his mother did – her new furniture. He asked her, and she was not supportive of his plans for the first time in his life.

Mrs. Gertrude had worked a long time to pay for her furniture and had no intentions of losing it. She did, however, want to be supportive of her son, so she told him, “I’ll just have to consult the Lord about this. It’s not a decision I can make by myself.” After about four days of praying and crying together, she believed the Lord wanted her to make the sacrifice, so she turned over the receipts on her furniture, and Johnson had a $500 check shortly after that. He sent out his letters that June, and as a result, approximately 3,000 people mailed in $2 towards Johnson’s vision. The next step was to make the magazine exist.

Johnson made many connections working for Supreme Life, three of which were vital to the magazine’s creation: Jay Jackson, an artist and cartoonist who provided the graphics; Ben Burns, a freelance writer who helped Johnson with writing content; and Earl Dickerson, who gave him an office space to work and his new company a place to exist. With these three things in place, along with him and his wife, Eunice, to make up the slack, everything was set except a printer and money to print.

For this, Johnson reached back to one of his “shit detail” job duties as the Multilith operator, which required Johnson to work closely with the Progress Printing Company to print Supreme Life’s printed materials. So when he went to Progress to make his print request on the basis of credit, he referred to it as a “we (him as an employee of Supreme Life)” effort. The printer assumed the magazine would be backed or was owned by Supreme Life and agreed with no apprehension of repayment. Thus, due to multiple “shit detail” job duties, the Negro Digest was published on November 1, 1942, under the Negro Digest Publishing Company.

Johnson worked for Supreme Life Insurance Company until he could no longer do as the demand of his new venture became his focus. He eventually acquired most of Supreme Life Insurance Company’s interest in 1974 and became its CEO shortly after.

NEGRO DIGEST

“For my mother, Gertrude Johnson Williams, without whom this story would not have been possible. ”

Negro Digest (later “Black World”) was an instant hit with notable contributing names in the first issue, including Langston Hughes. Buzz started to build, and Johnson had to figure out where to sell the remaining 2,000 of 5,000 printed issues to pay his debt to the printer. He reached out to the Levy Circulating Company and asked the director to allow Negro Digest to be sold on its newsstands. The owner informed Johnson that Black publications didn’t sell, and so he was not going to take a chance on Negro Digest, ensuring him it was not because he was prejudice as he was a Jewish man.

Johnson left the Levy office and asked thirty friends at Supreme Life to go to the newsstands and ask for Negro Digest specifically throughout the course of a week. Not only did the method work, but Johnson resold the magazines after his friends bought them from the Levy newsstands.

Negro Digest reached 50,000 copies in monthly circulation nationally by the summer of 1943, as Johnson used the same newsstand strategy across the country. Circulation jumped to 100,000 almost over when former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt contributed a piece to the magazine, entitled “If I Were a Negro” in the October 1943 issue propelling the publication to the top.

With so much success generated since the first issue of Negro Digest’s debut, Johnson began planning a Black version of Life Magazine. It would include fancy pictures of Black people getting married, being in beauty contests, having parties, as successful businesswomen and men, and other positive things Black people were doing every day. Johnson’s underlined effort was to counter the unspoken rule that Black pictures could not be published in print unless it was for a crime.

His wife named it EBONY Magazine, and it debuted on November 1, 1945. Its focus is to showcase Black people in achievement, religion, education, music, beauty, medicine, fashion, and everyday life. Its advertisements promoted general products that any race would purchase and those specifically designed for the Black consumer, such as hair straighteners. Many Black readers appreciated this approach and the magazine, and it accumulated over 2.5 million readers, becoming Johnson’s most successful monthly publication.

“For my mother, Gertrude Johnson Williams, without whom this story would not have been possible. ”

Negro Digest (later “Black World”) was an instant hit with notable contributing names in the first issue, including Langston Hughes. Buzz started to build, and Johnson had to figure out where to sell the remaining 2,000 of 5,000 printed issues to pay his debt to the printer. He reached out to the Levy Circulating Company and asked the director to allow Negro Digest to be sold on its newsstands. The owner informed Johnson that Black publications didn’t sell, and so he was not going to take a chance on Negro Digest, ensuring him it was not because he was prejudice as he was a Jewish man.

Johnson left the Levy office and asked thirty friends at Supreme Life to go to the newsstands and ask for Negro Digest specifically throughout the course of a week. Not only did the method work, but Johnson resold the magazines after his friends bought them from the Levy newsstands.

Negro Digest reached 50,000 copies in monthly circulation nationally by the summer of 1943, as Johnson used the same newsstand strategy across the country. Circulation jumped to 100,000 almost over when former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt contributed a piece to the magazine, entitled “If I Were a Negro” in the October 1943 issue propelling the publication to the top.

With so much success generated since the first issue of Negro Digest’s debut, Johnson began planning a Black version of Life Magazine. It would include fancy pictures of Black people getting married, being in beauty contests, having parties, as successful businesswomen and men, and other positive things Black people were doing every day. Johnson’s underlined effort was to counter the unspoken rule that Black pictures could not be published in print unless it was for a crime.

His wife named it EBONY Magazine, and it debuted on November 1, 1945. Its focus is to showcase Black people in achievement, religion, education, music, beauty, medicine, fashion, and everyday life. Its advertisements promoted general products that any race would purchase and those specifically designed for the Black consumer, such as hair straighteners. Many Black readers appreciated this approach and the magazine, and it accumulated over 2.5 million readers, becoming Johnson’s most successful monthly publication.

JOHNSON PUBLISHING COMPANY

“The reason I succeeded was because I didn’t know it was impossible to succeed.”

Johnson’s new company was a privately held, family-owned, and -operated enterprise. When it celebrated the first anniversary of EBONY in November 1946, its financial future was still uncertain. Circulations were great, but the publications had no advertisings. So Johnson decided to create multiple businesses that would produce revenue to pay for the advertising he needed but couldn’t get.

Beauty Star Cosmetics was of those businesses, which marketed hair care products such as “Sateen.” There was also Supreme Beauty products (a spinoff of Beauty Star), Linda Fashions - a mail-order company that sold dresses and clothes, a wig line called “Star Glow,” businesses that sold vitamins and books, and a Negro Digest bookshop.

These businesses gave Johnson room to financially maneuver through each issue until he could secure advertising accounts with significant corporations. In addition to this, Johnson managed to get Lena Horne on the November 1947 cover, which sold 333,445 copies and positioned the company for a physical need for more space. As a result, it relocated to 1820 South Michigan Avenue in a prestigious part of Chicago.

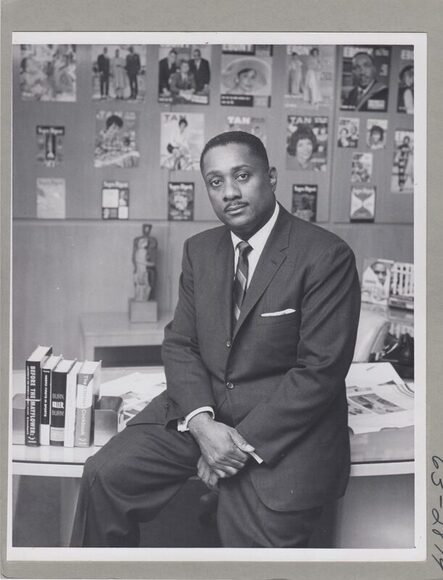

As EBONY’s success increased, Negro Digest decreased, and Johnson discontinued it in 1951. JET Magazine soon followed with its debut on November 1, 1951, and became the company’s number-one newsweekly magazine with more than nine million subscribers. Its purpose is to do the same as EBONY but to highlight current news on Blacks in the social limelight, events, politics, entertainment, business, and sports.

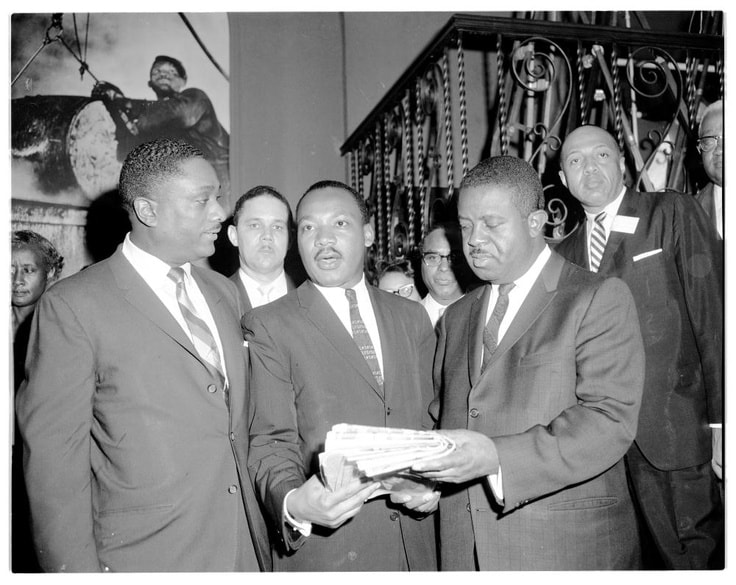

Together EBONY and JET covered Black culture, demanded equality for Blacks in American life, and were forms of Black protest, advocacy, and activism. Johnson used both platforms to answer the call of media leadership to attend and report the voices of the unrest throughout the nation. Three of its noted news coverages were the March on Washington with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and several other civil rights activists, the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, and the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

EBONY was selling 900,000 copies per month by its 20th anniversary in 1965 and took on a greater leadership role as interest in Black History grew in Black communities. Simultaneously, and throughout its existence, political leaders held EBONY in high regard, including Richard Nixon, John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Ronald Reagan, and Bill Clinton. In addition, Johnson was asked to serve as an Ambassador on behalf of the United States, making appearances in countries worldwide.

Johnson Publishing Company eventually expanded into radio after Johnson bought the WGRT radio station and converted it into the WJPC AM, the first black-owned radio station in Chicago. He then acquired the suburban WLNR FM radio station and changed the format. Shortly after that, Johnson broke into television as a sponsor for several shows, including the American Black Achievement Awards Show, Ebony and Jet Showcase, and the Ebony Music Awards show.

Other magazines birthed from the Johnson Publishing Company (formally the Negro Digest Publishing Company) included Ebony Jr., Tan (or Tan Confessions), Hue, Cooper (or Cooper Romance), EM (or Ebony Man), and Black Stars Magazine. All the publications were designed to provide information and inspiration to Black people from Black people by Black people—Johnson’s constant form of Black representation.

Another venture that the Johnson Publishing Company undertook was the Ebony Fashion Fair in 1958, with Eunice Walker Johnson leading as director. It was the world’s largest traveling fashion show and has raised over $50 million for charities to date, most of which went toward college scholarships. In recent years, it has attracted an average of 300,000 patrons annually.

After the constant difficulties of finding makeup that matched the complexion of the Fashion Fair’s Black, Latina, and dark-skinned white touring models, Johnson expanded his brand again by starting the Fashion Fair Cosmetics line in 1973. This branch of Johnson’s company is among the top, high-quality makeup and skin-care companies for women with darker skin. It was also the largest Black-owned cosmetics operation globally and ranked in the top ten cosmetics lines sold in department stores.

“The reason I succeeded was because I didn’t know it was impossible to succeed.”

Johnson’s new company was a privately held, family-owned, and -operated enterprise. When it celebrated the first anniversary of EBONY in November 1946, its financial future was still uncertain. Circulations were great, but the publications had no advertisings. So Johnson decided to create multiple businesses that would produce revenue to pay for the advertising he needed but couldn’t get.

Beauty Star Cosmetics was of those businesses, which marketed hair care products such as “Sateen.” There was also Supreme Beauty products (a spinoff of Beauty Star), Linda Fashions - a mail-order company that sold dresses and clothes, a wig line called “Star Glow,” businesses that sold vitamins and books, and a Negro Digest bookshop.

These businesses gave Johnson room to financially maneuver through each issue until he could secure advertising accounts with significant corporations. In addition to this, Johnson managed to get Lena Horne on the November 1947 cover, which sold 333,445 copies and positioned the company for a physical need for more space. As a result, it relocated to 1820 South Michigan Avenue in a prestigious part of Chicago.

As EBONY’s success increased, Negro Digest decreased, and Johnson discontinued it in 1951. JET Magazine soon followed with its debut on November 1, 1951, and became the company’s number-one newsweekly magazine with more than nine million subscribers. Its purpose is to do the same as EBONY but to highlight current news on Blacks in the social limelight, events, politics, entertainment, business, and sports.

Together EBONY and JET covered Black culture, demanded equality for Blacks in American life, and were forms of Black protest, advocacy, and activism. Johnson used both platforms to answer the call of media leadership to attend and report the voices of the unrest throughout the nation. Three of its noted news coverages were the March on Washington with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and several other civil rights activists, the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, and the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

EBONY was selling 900,000 copies per month by its 20th anniversary in 1965 and took on a greater leadership role as interest in Black History grew in Black communities. Simultaneously, and throughout its existence, political leaders held EBONY in high regard, including Richard Nixon, John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Ronald Reagan, and Bill Clinton. In addition, Johnson was asked to serve as an Ambassador on behalf of the United States, making appearances in countries worldwide.

Johnson Publishing Company eventually expanded into radio after Johnson bought the WGRT radio station and converted it into the WJPC AM, the first black-owned radio station in Chicago. He then acquired the suburban WLNR FM radio station and changed the format. Shortly after that, Johnson broke into television as a sponsor for several shows, including the American Black Achievement Awards Show, Ebony and Jet Showcase, and the Ebony Music Awards show.

Other magazines birthed from the Johnson Publishing Company (formally the Negro Digest Publishing Company) included Ebony Jr., Tan (or Tan Confessions), Hue, Cooper (or Cooper Romance), EM (or Ebony Man), and Black Stars Magazine. All the publications were designed to provide information and inspiration to Black people from Black people by Black people—Johnson’s constant form of Black representation.

Another venture that the Johnson Publishing Company undertook was the Ebony Fashion Fair in 1958, with Eunice Walker Johnson leading as director. It was the world’s largest traveling fashion show and has raised over $50 million for charities to date, most of which went toward college scholarships. In recent years, it has attracted an average of 300,000 patrons annually.

After the constant difficulties of finding makeup that matched the complexion of the Fashion Fair’s Black, Latina, and dark-skinned white touring models, Johnson expanded his brand again by starting the Fashion Fair Cosmetics line in 1973. This branch of Johnson’s company is among the top, high-quality makeup and skin-care companies for women with darker skin. It was also the largest Black-owned cosmetics operation globally and ranked in the top ten cosmetics lines sold in department stores.

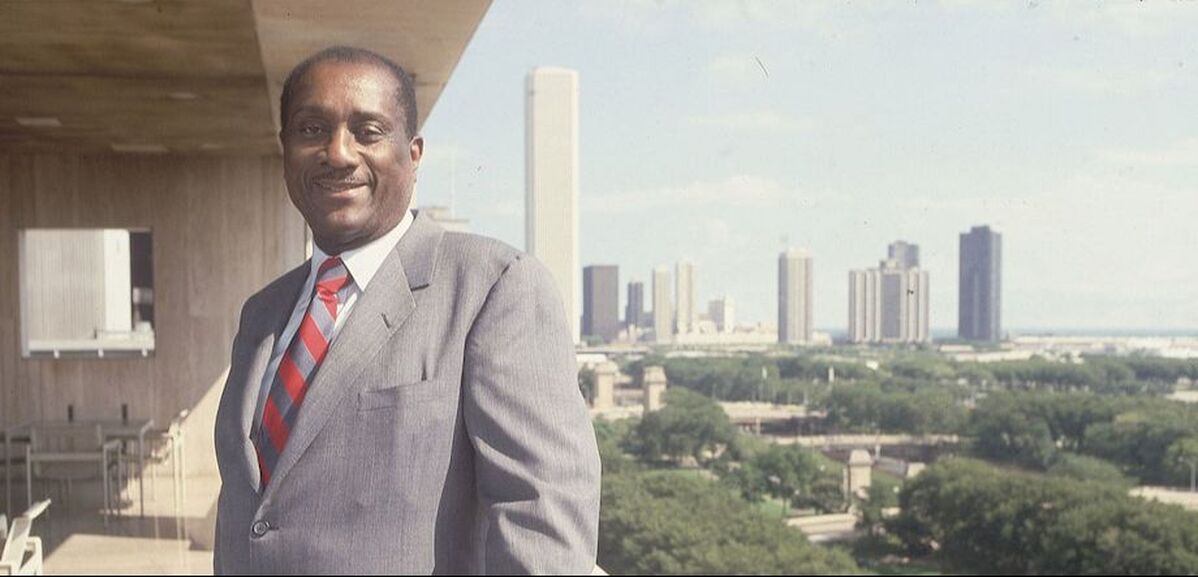

LANDMARK BUILDING

The Johnson Publishing Company’s physical headquarters was built in 1971 and represented Johnson’s pride and support of the Black culture. It was designed by a Black man, John Moutoussamy, who became the first Black architect to design a high-rise building in Chicago, which remains the only Chicago high-rise designed by a Black person to date.

The City of Chicago designated the Johnson Publishing Company Building as a city landmark in the fall of 2017, and it has been repurposed for rental apartments by the 3L Real Estate company who specializes in classic real estate. The intentionally maintains and preserves original features of the building, including the décor of the iconic, psychedelic Ebony Test Kitchen, the original Ebony/Jet sign that sits atop the building, and the large swaths of original wood wall paneling.

The Johnson Publishing Company’s physical headquarters was built in 1971 and represented Johnson’s pride and support of the Black culture. It was designed by a Black man, John Moutoussamy, who became the first Black architect to design a high-rise building in Chicago, which remains the only Chicago high-rise designed by a Black person to date.

The City of Chicago designated the Johnson Publishing Company Building as a city landmark in the fall of 2017, and it has been repurposed for rental apartments by the 3L Real Estate company who specializes in classic real estate. The intentionally maintains and preserves original features of the building, including the décor of the iconic, psychedelic Ebony Test Kitchen, the original Ebony/Jet sign that sits atop the building, and the large swaths of original wood wall paneling.

TORCH PASSED

Johnson broke down and overcame racial barriers and discrimination for Black people in banking, real estate, and advertisement in Chicago and across the United States. He achieved an abundance of success in his life and beat many odds set against him, systemic and otherwise. His impact helped shape multiple generations of Black culture and the world’s perception of it by giving them a voice and a platform to be heard.

Through the successes acquired by this company, thousands of opportunities were created for Black skillsets and talents who may have not otherwise had one, including models, photographers, writers, advertising specialists, creatives, entrepreneurs, accountants, and other professionals. Even for Johnson’s daughter, Linda, who became the CEO of Johnson Publishing Company in 2002 while he remained the chairman and publisher.

Johnson Publishing Company sold EBONY and Jet Magazines to a private equity firm to oversee operations, creating the Ebony Media company in 2016. Recently, Ulysses Bridgeman, a former NBA Basketball player, successfully won his $14 million ownership bid for the assets of Ebony Media by a Houston bankruptcy court and hired Michele (Thornton) Ghee as the new CEO of Ebony and Jet. Unfortunately, Johnson Publishing Company filed for bankruptcy on April 9, 2019.

Johnson broke down and overcame racial barriers and discrimination for Black people in banking, real estate, and advertisement in Chicago and across the United States. He achieved an abundance of success in his life and beat many odds set against him, systemic and otherwise. His impact helped shape multiple generations of Black culture and the world’s perception of it by giving them a voice and a platform to be heard.

Through the successes acquired by this company, thousands of opportunities were created for Black skillsets and talents who may have not otherwise had one, including models, photographers, writers, advertising specialists, creatives, entrepreneurs, accountants, and other professionals. Even for Johnson’s daughter, Linda, who became the CEO of Johnson Publishing Company in 2002 while he remained the chairman and publisher.

Johnson Publishing Company sold EBONY and Jet Magazines to a private equity firm to oversee operations, creating the Ebony Media company in 2016. Recently, Ulysses Bridgeman, a former NBA Basketball player, successfully won his $14 million ownership bid for the assets of Ebony Media by a Houston bankruptcy court and hired Michele (Thornton) Ghee as the new CEO of Ebony and Jet. Unfortunately, Johnson Publishing Company filed for bankruptcy on April 9, 2019.

RECOGNITION

John H. Johnson has acquired a myriad of awards, recognitions, and honors. He has been inducted into the Arkansas Business Hall of Fame, the Junior Achievement National Business Hall of Fame, the Advertising Hall of Fame, the Chicago Journalism Hall of Fame, the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame, and the National Business Hall of Fame.

Johnson has also received over thirty honorary doctorate degrees from universities such as the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff, the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, Harvard University, and Howard University. Howard University also named its school of communication the John H. Johnson School of Communication.

He has received the Spingarn Medal and “Publisher of the Year” award from the NAACP in 1972. He was also awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1996 by former U.S. President Bill Clinton on the 50th anniversary of EBONY Magazine. This is the highest civilian honor in America.

The John H. Johnson Museum and Educational Center opened its doors to the public in Arkansas City in 2005. It is a replica of his childhood home that commemorates the story of Johnson’s life along the Mississippi River levee to his title of the founder of Johnson Publishing Company.

As a part of the U.S. Postal Service’s Black Heritage series, a first-class stamp was released honoring Johnson in January 2012.

SEASONS OF SORROW

Inclusive of all the successes that the company acquired, there were losses as well. Some of business matters and others of natural occurrence referred to in Johnson’s autobiography, Succeeding Against the Odds, as “Seasons of Sorrows.” A few of those seasons were the passing of Mr. James Williams in 1961, Mrs. Gertrude Johnson Williams' passing on Sunday, May 1, 1977, and the passing of John, Jr. on Sunday, December 20, 1981, after a long battle against sickle cell anemia. His wife, Eunice, died on January 3, 2010. She remained the producer and director of the Ebony Fashion Fair until her death.

John H. Johnson has acquired a myriad of awards, recognitions, and honors. He has been inducted into the Arkansas Business Hall of Fame, the Junior Achievement National Business Hall of Fame, the Advertising Hall of Fame, the Chicago Journalism Hall of Fame, the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame, and the National Business Hall of Fame.

Johnson has also received over thirty honorary doctorate degrees from universities such as the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff, the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, Harvard University, and Howard University. Howard University also named its school of communication the John H. Johnson School of Communication.

He has received the Spingarn Medal and “Publisher of the Year” award from the NAACP in 1972. He was also awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1996 by former U.S. President Bill Clinton on the 50th anniversary of EBONY Magazine. This is the highest civilian honor in America.

The John H. Johnson Museum and Educational Center opened its doors to the public in Arkansas City in 2005. It is a replica of his childhood home that commemorates the story of Johnson’s life along the Mississippi River levee to his title of the founder of Johnson Publishing Company.

As a part of the U.S. Postal Service’s Black Heritage series, a first-class stamp was released honoring Johnson in January 2012.

SEASONS OF SORROW

Inclusive of all the successes that the company acquired, there were losses as well. Some of business matters and others of natural occurrence referred to in Johnson’s autobiography, Succeeding Against the Odds, as “Seasons of Sorrows.” A few of those seasons were the passing of Mr. James Williams in 1961, Mrs. Gertrude Johnson Williams' passing on Sunday, May 1, 1977, and the passing of John, Jr. on Sunday, December 20, 1981, after a long battle against sickle cell anemia. His wife, Eunice, died on January 3, 2010. She remained the producer and director of the Ebony Fashion Fair until her death.