ARKANSAS BLACK HISTORY // Location

The Line

West 9th Street & Dreamland

by Dianna Donahue - Feb.01.2021

There is a 3-story, brick building that sits along I-630 West on West 9th Street adorned in patriotic American bunting. There are not many other buildings on the street or a significant amount of consistent traffic, but that has not always been the case. It may be difficult to imagine it today, but this building – and the street it sits on – were once the heart of the Black business district for the city of Little Rock. Born from Arkansas’ emancipation of slaves, West 9th Street thrived economically from Black dollars circulated through Black-owned businesses spanning six blocks long.

The lone building, Taborian Hall, helped continue this momentum throughout those years. It catered to Black soldiers of World War I & II, hosted social events, boxing matches, dances, and basketball games. It was one of the Chitlin’ Circuit’s prime stops making West 9th Street Little Rock’s Beale Street attracting well-noted Black entertainers, such as Cab Calloway, Etta James, Red Foxx, Duke Ellington, Sammie Davis, Jr., Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Louis Armstrong, B.B. King, Sam Cooke, and Ray Charles.

The story and legacy of the building and the street does not get the consistent notoriety that it deserves, but its relevance to Black Arkansas remains the same. To fully appreciate that relevance, you must – at the very least – understand the history of West 9th Street. An ideal place to start is November 6, 1860.

The lone building, Taborian Hall, helped continue this momentum throughout those years. It catered to Black soldiers of World War I & II, hosted social events, boxing matches, dances, and basketball games. It was one of the Chitlin’ Circuit’s prime stops making West 9th Street Little Rock’s Beale Street attracting well-noted Black entertainers, such as Cab Calloway, Etta James, Red Foxx, Duke Ellington, Sammie Davis, Jr., Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Louis Armstrong, B.B. King, Sam Cooke, and Ray Charles.

The story and legacy of the building and the street does not get the consistent notoriety that it deserves, but its relevance to Black Arkansas remains the same. To fully appreciate that relevance, you must – at the very least – understand the history of West 9th Street. An ideal place to start is November 6, 1860.

A COUNTRY DIVIDED

Abraham Lincoln was elected president of the United States in 1860 amid decade-long tensions over slavery. Several southern state governments disapproved of President Lincoln's election and his goals, thus positioned themselves to secede from the United States of America – also called the Union. By February 1, 1861, seven states proceeded with their secession, dividing the United States of America into the Union and the Confederate States of America – better known as the Confederacy.

Arkansas’ government rejected seceding with the Confederacy out of concern of its image. However, opposing influences initiated reconsideration, and Arkansas voters elected for a Secession Convention to determine its official stance on February 18, 1861. The convention began in early March after President Lincoln was sworn into office. On April 12, he ordered troops from Arkansas (Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee) to recapture Fort Sumter in Charleston, North Carolina from the Confederacy. Arkansas did not want to fight against its neighboring states, so the Secession Convention adjourned with Arkansas joining the Confederacy on May 6th, 1861.

These occurrences, and other long-lived discrepancies before them, incited the beginning of the Civil War on April 12, 1861. Since the primary cause of it all was the right to own slaves, President Lincoln issued an executive order called the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. It stated that "all persons held as slaves…are, and henceforward shall be free". Unfortunately, the Confederacy would not conform, and the war continued state by state.

On September 10, 1863, the Engagement at Bayou Fourche, or the Battle of Little Rock, took place along the Arkansas River east of Willow Beach Lake, just east of Bill & Hillary Clinton National Airport. It resulted in a Union victory and the first time that the Union had complete control of the Arkansas River since the war began.

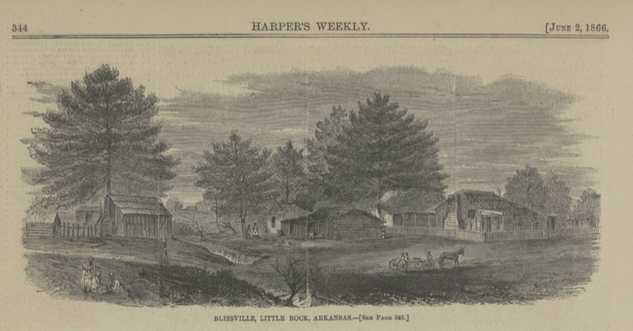

Arkansas did not emancipate slaves until April 14, 1865, but the Bayou Fourche victory set it in motion, and slave owners had to release their slaves. The emancipated slaves migrated by foot or were brought to a federal, Union-occupied encampment in Little Rock, just west of Mount Holly Cemetery, not too far from what will be known as West 9th Street. There were so many of them that military commanders had to create housing for them hastily, which consisted of tents and shacks. The area would be called Blissville.

Abraham Lincoln was elected president of the United States in 1860 amid decade-long tensions over slavery. Several southern state governments disapproved of President Lincoln's election and his goals, thus positioned themselves to secede from the United States of America – also called the Union. By February 1, 1861, seven states proceeded with their secession, dividing the United States of America into the Union and the Confederate States of America – better known as the Confederacy.

Arkansas’ government rejected seceding with the Confederacy out of concern of its image. However, opposing influences initiated reconsideration, and Arkansas voters elected for a Secession Convention to determine its official stance on February 18, 1861. The convention began in early March after President Lincoln was sworn into office. On April 12, he ordered troops from Arkansas (Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee) to recapture Fort Sumter in Charleston, North Carolina from the Confederacy. Arkansas did not want to fight against its neighboring states, so the Secession Convention adjourned with Arkansas joining the Confederacy on May 6th, 1861.

These occurrences, and other long-lived discrepancies before them, incited the beginning of the Civil War on April 12, 1861. Since the primary cause of it all was the right to own slaves, President Lincoln issued an executive order called the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. It stated that "all persons held as slaves…are, and henceforward shall be free". Unfortunately, the Confederacy would not conform, and the war continued state by state.

On September 10, 1863, the Engagement at Bayou Fourche, or the Battle of Little Rock, took place along the Arkansas River east of Willow Beach Lake, just east of Bill & Hillary Clinton National Airport. It resulted in a Union victory and the first time that the Union had complete control of the Arkansas River since the war began.

Arkansas did not emancipate slaves until April 14, 1865, but the Bayou Fourche victory set it in motion, and slave owners had to release their slaves. The emancipated slaves migrated by foot or were brought to a federal, Union-occupied encampment in Little Rock, just west of Mount Holly Cemetery, not too far from what will be known as West 9th Street. There were so many of them that military commanders had to create housing for them hastily, which consisted of tents and shacks. The area would be called Blissville.

PROSPEROUS RACE

As Arkansas entered 1870, Reconstruction allowed for more race-tolerant and progressive practices than most other southern states despite the fog of Jim Crow. There were integrated housing patterns, and with the new state constitution, Black men could vote; there were twenty Black men in the Arkansas General Assembly by 1873, and, for the first time, there was a Black urban middle class in Blissville. Since many of the area were skilled and well-educated, Blissville was able to thrive and become the core of the Black commercial district in Arkansas. The tents and shacks that once made up the shantytown were replaced with homes and Black-owned businesses from Broadway to Ringo Street. Of those businesses was the National Grand Temple Headquarters by the Temple Mosaic Templars of America, founded by John E. Bush and Chester W. Keatts, two former slaves; and the Taborian Temple by the International Order of the Twelve Knights and Daughters of Tabor, founded by Rev. Moses Dixon. Both entities established to assist and aid in the progression of Black people.

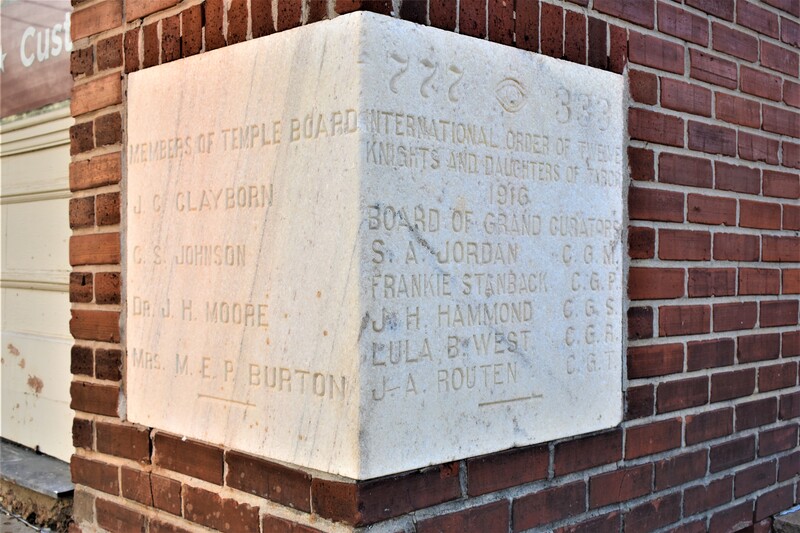

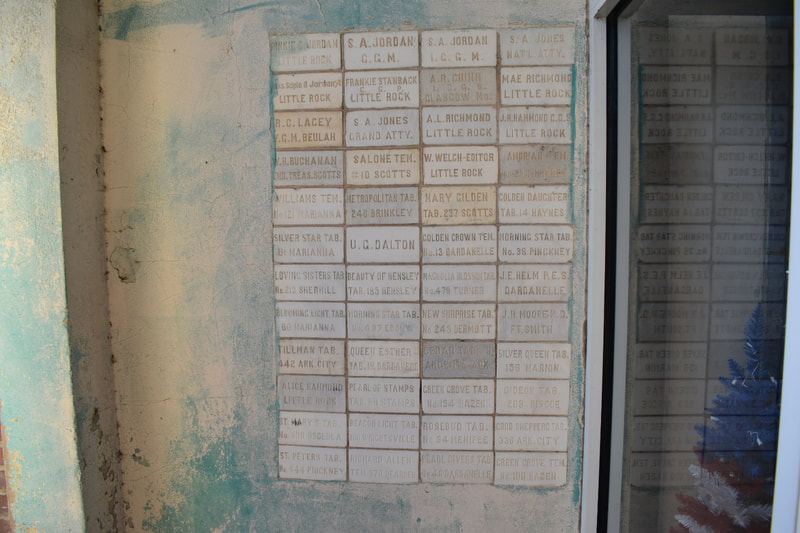

As Arkansas entered 1870, Reconstruction allowed for more race-tolerant and progressive practices than most other southern states despite the fog of Jim Crow. There were integrated housing patterns, and with the new state constitution, Black men could vote; there were twenty Black men in the Arkansas General Assembly by 1873, and, for the first time, there was a Black urban middle class in Blissville. Since many of the area were skilled and well-educated, Blissville was able to thrive and become the core of the Black commercial district in Arkansas. The tents and shacks that once made up the shantytown were replaced with homes and Black-owned businesses from Broadway to Ringo Street. Of those businesses was the National Grand Temple Headquarters by the Temple Mosaic Templars of America, founded by John E. Bush and Chester W. Keatts, two former slaves; and the Taborian Temple by the International Order of the Twelve Knights and Daughters of Tabor, founded by Rev. Moses Dixon. Both entities established to assist and aid in the progression of Black people.

The construction of Taborian Temple (later named Taborian Hall) began in 1916 at 800 West 9th Street under Scipio Africanus Jordan's leadership after Rev. Dixon died in 1901. The building was constructed by Black contractors and was paid for with Black dollars donated from Black fraternal organizations from across the state. The total cost of its construction was $65,000 (approximately $1,621,680.58 at today's value). Construction was completed in 1918 and served as the Grand Temple and Tabernacle of the Knights and Daughters of Tabor conducting local, state, and international service. It also housed several commercial and professional businesses, including a dentist and a doctor's office, a bar, a restaurant, and a recreational space in the basement for Black soldiers who were stationed at Camp Pike.

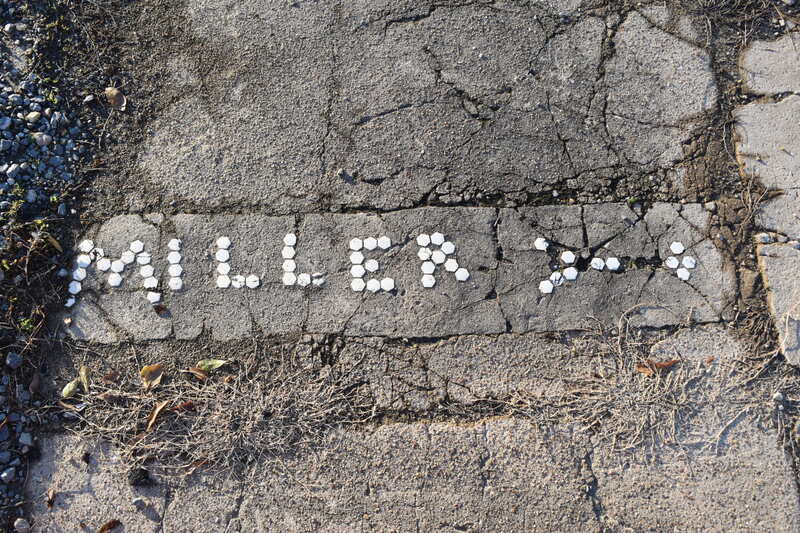

Taborian Temple helped attract many Black people to West 9th Street during its Golden Era of development. In turn, Black-owned businesses permeated the street, including beauty- and barbershops, grocery stores, offices for professionals, confectioners, bakers, and more. Black Arkansans would be deemed the "Prosperous Race" but still viewed as second-class to whites. West 9th Street would be considered a "city-within-a-city," but it was yet known as "The Line" to mark the Black community's physical limit into white society. Although opportunities were attainable and allowed in Arkansas, Jim Crow still existed. And it was growing.

Black Arkansans still simultaneously encountered racism despite the racial tolerance after emancipation. It spiked when Black World War I soldiers demanded respect at home for fighting for the United States across the ocean. By this time, the Confederacy reinvented their notions to appear moral and just under the Ku Klux Klan organization. These notions spread across the south, and many adopted murderous fear tactics to reinforce their option of racial hierarchy. Arkansas was no exception to this notion.

Taborian Temple helped attract many Black people to West 9th Street during its Golden Era of development. In turn, Black-owned businesses permeated the street, including beauty- and barbershops, grocery stores, offices for professionals, confectioners, bakers, and more. Black Arkansans would be deemed the "Prosperous Race" but still viewed as second-class to whites. West 9th Street would be considered a "city-within-a-city," but it was yet known as "The Line" to mark the Black community's physical limit into white society. Although opportunities were attainable and allowed in Arkansas, Jim Crow still existed. And it was growing.

Black Arkansans still simultaneously encountered racism despite the racial tolerance after emancipation. It spiked when Black World War I soldiers demanded respect at home for fighting for the United States across the ocean. By this time, the Confederacy reinvented their notions to appear moral and just under the Ku Klux Klan organization. These notions spread across the south, and many adopted murderous fear tactics to reinforce their option of racial hierarchy. Arkansas was no exception to this notion.

9th & BROADWAY

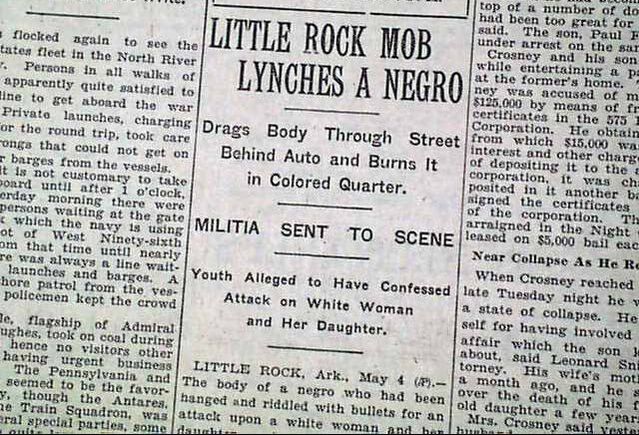

On May 27, 1927, thirty-eight-year-old John Carter was murdered by a white mob for a crime he did not commit. According to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, an "angry mob hanged him from a telephone pole and shot him. A caravan of cars then dragged Carter's mangled corpse through the streets of Little Rock, stopping at the intersection of 9th and Broadway, which at the time was the heart of the city's African-American community." The mob then broke into Bethel church (among other businesses), stole doors and pews, made a bonfire in the intersection, and set John Carter's remains on fire. Towards the end of the event, one of the thugs directed traffic with Carter's dismembered arm. Racial tolerance in Arkansas was no more.

DREAMLAND BALLROOM

West 9th Street pressed forward and continued to flourish until the residual effects of the Great Depression rested on the state towards the end of the 1920s. Unfortunately, many businesses on "The Line" could no longer afford to operate and closed their doors. The Knights and Daughters of Tabor were included in the cessation, and they lost ownership of Taborian Temple. From that point until around 1933, West 9th Street slowly revamped.

S.W. Tucker became the new owner of the Taborian Temple, and he created the Dreamland Ballroom on the third floor of the building under his ownership. It was a beautiful venue where many Black social events and parties happened and was the center of "The Line's" appeal. The Chicago Defender describes Dreamland as "beautiful and spacious" in 1936. The writer recounts the success of the Les Quatre Roses Club's first annual dance held there: "Approximately two hundred and fifty guests enjoyed the music of Billy Holloway and tripped the light fantastic until the wee hours of the morning." It went on to say Dreamland would be a music epicenter. This proved true as Tucker positioned it to be an imperative spot on the Chitlin' Circuit for Black musical performers.

West 9th Street pressed forward and continued to flourish until the residual effects of the Great Depression rested on the state towards the end of the 1920s. Unfortunately, many businesses on "The Line" could no longer afford to operate and closed their doors. The Knights and Daughters of Tabor were included in the cessation, and they lost ownership of Taborian Temple. From that point until around 1933, West 9th Street slowly revamped.

S.W. Tucker became the new owner of the Taborian Temple, and he created the Dreamland Ballroom on the third floor of the building under his ownership. It was a beautiful venue where many Black social events and parties happened and was the center of "The Line's" appeal. The Chicago Defender describes Dreamland as "beautiful and spacious" in 1936. The writer recounts the success of the Les Quatre Roses Club's first annual dance held there: "Approximately two hundred and fifty guests enjoyed the music of Billy Holloway and tripped the light fantastic until the wee hours of the morning." It went on to say Dreamland would be a music epicenter. This proved true as Tucker positioned it to be an imperative spot on the Chitlin' Circuit for Black musical performers.

West 9th Street was a musicians' hangout because there were so many places to perform. Just about, if not every week, Dreamland itself hosted an entertainer. Fats Waller, W.C. Handy, Otis Redding, Dinah Washington, Clarence Carter, Howling Wolf, Count Basie, Lionel Hampton, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, and, Brinkley, Arkansas's own, Louis Jordan are just a few of the internationally known names that performed there. The Black culture was vibrant on "The Line." In most instances, the entertainers performed at the Robinson Auditorium for the white audience then headed straight to West 9th Street to Dreamland for "the real party."

The United States' Officer's Club, or the USO, eventually purchased Taborian Temple in 1942 and renovated it, adding a vaulted ceiling to the third floor, an additional balcony, a chimney, a fresh coat of paint, and turning the basement into a nightclub. As the soldiers returned home or were stationed at Camp Robinson or Stuttgart Air Base during World War II, they flocked to West 9th Street to unwind and breathe. And as soldiers' dollars came to the street, Black businesses began opening along the street again. Unfortunately, West 9th Street's history did repeat itself in the form of the murder of another Black man under the notion of white superiority.

The United States' Officer's Club, or the USO, eventually purchased Taborian Temple in 1942 and renovated it, adding a vaulted ceiling to the third floor, an additional balcony, a chimney, a fresh coat of paint, and turning the basement into a nightclub. As the soldiers returned home or were stationed at Camp Robinson or Stuttgart Air Base during World War II, they flocked to West 9th Street to unwind and breathe. And as soldiers' dollars came to the street, Black businesses began opening along the street again. Unfortunately, West 9th Street's history did repeat itself in the form of the murder of another Black man under the notion of white superiority.

DEMAND RESPECT

On March 22, 1942, Sergeant Thomas P. Foster, a native of North Carolina, was shot and killed on West 9th Street for questioning Officer Abner J. Hay's – a white man – his reason for beating and arresting one of his company's soldiers – a Black man. He also asked the MPs – white men – why did they not stop the assault. Even though Sergeant Foster outranked them, the MPs still tried to arrest him but were unsuccessful as the sergeant made a run for it. The chase ended in a nook on the front side of a Black Presbyterian church where he was beaten with a nightstick by the LRPD officer as MPs watched "brandishing guns to hold the crowd back." Seeming to have the upper hand over Hay, he shot Sergeant Foster five times while he lay unarmed on the ground.

Racial injustices made the 1940s through the 1960s an extremely tense time in Little Rock, but West 9th Street was thriving economically. Taborian Temple's name changed to Taborian Hall by 1954, and the floor assignment converted into three nightclubs: Dreamland still occupied the third floor (now call Club Morocco), the Waiters Club was on the second floor, and the Twin City Club was in the basement. These club spots drew people nightly as it offered refuge for Black people to breathe, relax, and escape the world outside.

On March 22, 1942, Sergeant Thomas P. Foster, a native of North Carolina, was shot and killed on West 9th Street for questioning Officer Abner J. Hay's – a white man – his reason for beating and arresting one of his company's soldiers – a Black man. He also asked the MPs – white men – why did they not stop the assault. Even though Sergeant Foster outranked them, the MPs still tried to arrest him but were unsuccessful as the sergeant made a run for it. The chase ended in a nook on the front side of a Black Presbyterian church where he was beaten with a nightstick by the LRPD officer as MPs watched "brandishing guns to hold the crowd back." Seeming to have the upper hand over Hay, he shot Sergeant Foster five times while he lay unarmed on the ground.

Racial injustices made the 1940s through the 1960s an extremely tense time in Little Rock, but West 9th Street was thriving economically. Taborian Temple's name changed to Taborian Hall by 1954, and the floor assignment converted into three nightclubs: Dreamland still occupied the third floor (now call Club Morocco), the Waiters Club was on the second floor, and the Twin City Club was in the basement. These club spots drew people nightly as it offered refuge for Black people to breathe, relax, and escape the world outside.

MANIPULATIVE SEGRERGATION

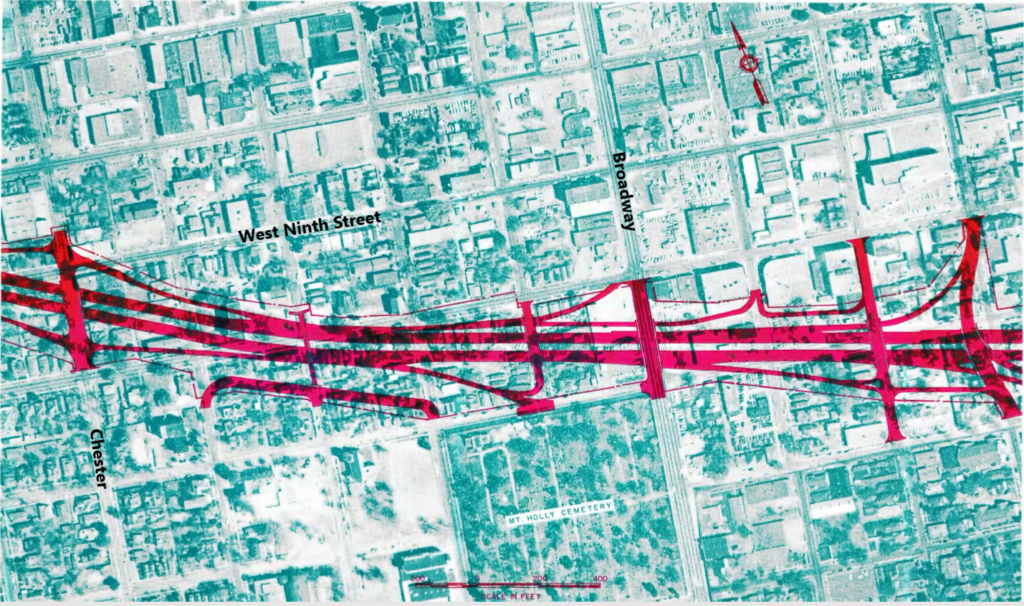

As Jim Crow slowly breaks down in Little Rock by way of new desegregation laws, geographical segregation methods from the early 1930s are revisited, specifically constructing the 8th street or East-to-West Expressway (today known as the I-630 freeway). This expressway would disband Little Rock's Black areas on and around West 9th Street and move them south, east, and southeast of downtown. Two high schools were built to proactively accommodate the intent: Horace Mann High School for the Black neighborhood built in 1955, and Hall High School for the white neighborhood built in 1957. This development left the newly integrated Central High School available for all races to attend.

The Little Rock Housing Authority proceeded with building housing projects in areas far from downtown, manipulatively relocating Blacks from their neighborhoods, including West 9th Street, established in the Reconstruction. The procedure was called "Urban Renewal," but it was eventually known as the "Negro Removal" as the intent became plain and repetitive across the country. Relocated patrons stopped visiting West 9th Street as frequently, and businesses struggled to stay open as revenue turnover started to dwindle.

Dreamland Ballroom closed in 1959, opened again under different ownership, but closed again in 1965. Many businesses followed suit, and buildings often became vacant and rundown. The Little Rock Urban Renewal seized this strategized outcome to level the area. A 1959 Urban Development promotional video denotes: "Alarmed at the threat of a decaying downtown area, the city board of directors authorized the housing authority to prepare and file an application with the Urban Renewal Administration for federal participation in the renewal of the entire downtown." Simultaneously, the tentative plan to execute the 8th Street Expressway was officially established in 1958, a year after Central High School was desegregated. Later in 1970, the Little Rock Housing Authority would grant the construction of I-630, allowing it to run through West 9th Street, undoubtedly separating Black neighborhoods from downtown Little Rock. Black entrepreneurs still conducting business on West 9th Street were made to leave by choice or eminent domain, and, one-by-one, buildings were demolished by the end of the 1980s.

As Jim Crow slowly breaks down in Little Rock by way of new desegregation laws, geographical segregation methods from the early 1930s are revisited, specifically constructing the 8th street or East-to-West Expressway (today known as the I-630 freeway). This expressway would disband Little Rock's Black areas on and around West 9th Street and move them south, east, and southeast of downtown. Two high schools were built to proactively accommodate the intent: Horace Mann High School for the Black neighborhood built in 1955, and Hall High School for the white neighborhood built in 1957. This development left the newly integrated Central High School available for all races to attend.

The Little Rock Housing Authority proceeded with building housing projects in areas far from downtown, manipulatively relocating Blacks from their neighborhoods, including West 9th Street, established in the Reconstruction. The procedure was called "Urban Renewal," but it was eventually known as the "Negro Removal" as the intent became plain and repetitive across the country. Relocated patrons stopped visiting West 9th Street as frequently, and businesses struggled to stay open as revenue turnover started to dwindle.

Dreamland Ballroom closed in 1959, opened again under different ownership, but closed again in 1965. Many businesses followed suit, and buildings often became vacant and rundown. The Little Rock Urban Renewal seized this strategized outcome to level the area. A 1959 Urban Development promotional video denotes: "Alarmed at the threat of a decaying downtown area, the city board of directors authorized the housing authority to prepare and file an application with the Urban Renewal Administration for federal participation in the renewal of the entire downtown." Simultaneously, the tentative plan to execute the 8th Street Expressway was officially established in 1958, a year after Central High School was desegregated. Later in 1970, the Little Rock Housing Authority would grant the construction of I-630, allowing it to run through West 9th Street, undoubtedly separating Black neighborhoods from downtown Little Rock. Black entrepreneurs still conducting business on West 9th Street were made to leave by choice or eminent domain, and, one-by-one, buildings were demolished by the end of the 1980s.

A FRACTURE

Today, Taborian Hall is the only remaining original building of West 9th Street. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 29, 1982, but was left vacant for years, becoming an impromptu shelter for the homeless and squatters. In 1988, the City of Little Rock planned to demolish it, but the Arkansas Historic Preservation intervened and saved the building. Kerry McCoy bought it in 1991 and renovated it for her store, Arkansas Flag and Banner. She continues to renovate the building to make it more attractive for the public to view and visit. Affixed at 9th & State Street, Taborian Hall serves as an anchor opposite of the recently built Mosaic Templars Cultural Center that sits at 9th & Broadway Street. Together they remind Black Arkansas of what was, as well as what could be.

West 9th Street itself is a symbol of Black interdependency, communal bonds, and Black power in Little Rock. It provided opportunity to Black, educated, talented, skilled, professional, and progressive-minded emancipated slaves in its infancy and continued to do so for over a century. Residency to Black-owned hotels, restaurants and cafe, night clubs, barber and beauty shops, medical offices, churches, liquor stores, grocery stores, a cab company, a pawn shop, a stable yard, bakeries, and confectionaries, funeral homes, a theatre, pharmacies, alterations shops, pool halls, an insurance company, and a shoemaking service...West 9th Street's legacy is rich and worth sharing frequently. Musician Billy Sparks, Jr. declares it to be "the Mecca of the Black economy, and Dreamland Ballroom was the vehicle that carried [it]."

These types of historic Black treasures are prominent across the county. Do you know where your town’s West 9th Street is?

Today, Taborian Hall is the only remaining original building of West 9th Street. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 29, 1982, but was left vacant for years, becoming an impromptu shelter for the homeless and squatters. In 1988, the City of Little Rock planned to demolish it, but the Arkansas Historic Preservation intervened and saved the building. Kerry McCoy bought it in 1991 and renovated it for her store, Arkansas Flag and Banner. She continues to renovate the building to make it more attractive for the public to view and visit. Affixed at 9th & State Street, Taborian Hall serves as an anchor opposite of the recently built Mosaic Templars Cultural Center that sits at 9th & Broadway Street. Together they remind Black Arkansas of what was, as well as what could be.

West 9th Street itself is a symbol of Black interdependency, communal bonds, and Black power in Little Rock. It provided opportunity to Black, educated, talented, skilled, professional, and progressive-minded emancipated slaves in its infancy and continued to do so for over a century. Residency to Black-owned hotels, restaurants and cafe, night clubs, barber and beauty shops, medical offices, churches, liquor stores, grocery stores, a cab company, a pawn shop, a stable yard, bakeries, and confectionaries, funeral homes, a theatre, pharmacies, alterations shops, pool halls, an insurance company, and a shoemaking service...West 9th Street's legacy is rich and worth sharing frequently. Musician Billy Sparks, Jr. declares it to be "the Mecca of the Black economy, and Dreamland Ballroom was the vehicle that carried [it]."

These types of historic Black treasures are prominent across the county. Do you know where your town’s West 9th Street is?