ARKANSAS BLACK HISTORY // Location

Red Summer in Elaine

An Extreme Response

by Dianna Donahue - Feb.01.2022

The end of the Civil War in 1865 began a new era in American history called the Reconstruction Era, where the country processed through reinstating seceding states in the Union and establishing a legal status for all Black people.

The Gilded Age began around 1870, and there was a boom in industrialization, causing economic growth for parts of America. Political corruption, vast inequality, and poverty for all races grew, and the country struggled with – among other things – the fair treatment of Black people due to a general disposition of white supremacy. Civil disobedience and race riots in the name of white superiority increased across America in 1919, especially in the South. It was coined the “Red Summer.”

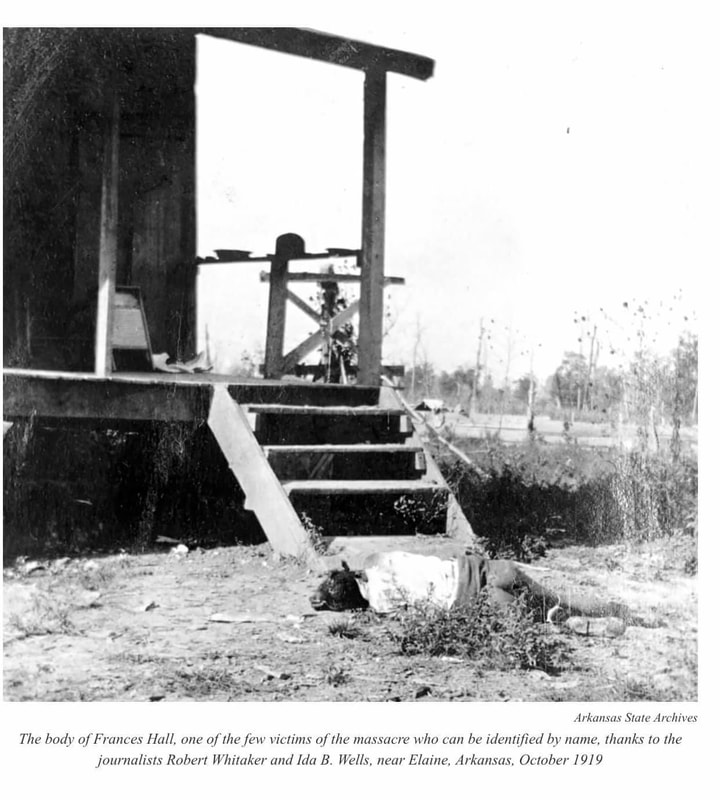

Many white Arkansans interpreted the Black gains and liberties after the Civil War as a form of inferiority to a biased racial hierarchy, triggering regularly displayed, racially motivated acts of violence against Black people to intimidate and preserve a racial disposition of social order. This included Black expulsion and unjustified race riots (often based on fabrications) used as a disciplinary effort in highly concentrated Black populations. In addition, lynchings, beatings, and murders were inclusive patterns – with the remains of the deceased still visible to serve as a warning to other Black people. Arkansas was no exception.

The state experienced a consistent surge in violence, and the authority of Jim Crow grew with every account of terrorism committed. One of those accounts happened in 1919 in rural Arkansas, before the Rosewood Race Riot in Florida or Oklahoma's Black Wall Street Massacre. It is commonly referred to as the Elaine Massacre.

The Gilded Age began around 1870, and there was a boom in industrialization, causing economic growth for parts of America. Political corruption, vast inequality, and poverty for all races grew, and the country struggled with – among other things – the fair treatment of Black people due to a general disposition of white supremacy. Civil disobedience and race riots in the name of white superiority increased across America in 1919, especially in the South. It was coined the “Red Summer.”

Many white Arkansans interpreted the Black gains and liberties after the Civil War as a form of inferiority to a biased racial hierarchy, triggering regularly displayed, racially motivated acts of violence against Black people to intimidate and preserve a racial disposition of social order. This included Black expulsion and unjustified race riots (often based on fabrications) used as a disciplinary effort in highly concentrated Black populations. In addition, lynchings, beatings, and murders were inclusive patterns – with the remains of the deceased still visible to serve as a warning to other Black people. Arkansas was no exception.

The state experienced a consistent surge in violence, and the authority of Jim Crow grew with every account of terrorism committed. One of those accounts happened in 1919 in rural Arkansas, before the Rosewood Race Riot in Florida or Oklahoma's Black Wall Street Massacre. It is commonly referred to as the Elaine Massacre.

ELAINE, ARKANSAS

Harry Kelley received word that Phillips County’s swamplands would be the richest part of Arkansas because the silt from the Mississippi River flooding would create fertile farmland in that area. He began to purchase land across the county in 1892, eventually owning approximately 35,000 acres.

As the predominant landowner of the county, Kelley began to establish it as a town around 1911, naming it Elaine. He and his business partner developed the lots of the town with the calculated intention of keeping the races in separate neighborhoods dividing them with Main Street. The Black areas were often referred to as “Quarters” in reference to slave quarters. Some Black areas of Elaine were still referenced this way in the latter part of the 20th Century.

The town grew as wooded areas were cleared for Plantations, concrete sidewalks and paved streets were laid, electricity was brought in, brick stores and a schoolhouse were built, and a 1,600-feet-deep well was dug that provided water to all parts of Elaine. It was incorporated on April 23, 1919, to solidify its presence.

Harry Kelley received word that Phillips County’s swamplands would be the richest part of Arkansas because the silt from the Mississippi River flooding would create fertile farmland in that area. He began to purchase land across the county in 1892, eventually owning approximately 35,000 acres.

As the predominant landowner of the county, Kelley began to establish it as a town around 1911, naming it Elaine. He and his business partner developed the lots of the town with the calculated intention of keeping the races in separate neighborhoods dividing them with Main Street. The Black areas were often referred to as “Quarters” in reference to slave quarters. Some Black areas of Elaine were still referenced this way in the latter part of the 20th Century.

The town grew as wooded areas were cleared for Plantations, concrete sidewalks and paved streets were laid, electricity was brought in, brick stores and a schoolhouse were built, and a 1,600-feet-deep well was dug that provided water to all parts of Elaine. It was incorporated on April 23, 1919, to solidify its presence.

COTTON

Like many counties and states in the South before the Civil War, a great portion of Phillips County’s land was developed to grow cotton. Thousands of acres of farmland were created and grossly depended on the labor of enslaved Black people to maintain it with little to no rightful compensation. In contrast, their labor created generational wealth for major landowners and planters since cotton was a top commodity well into the 20th century.

Once the Civil War concluded, abolishing the institution of slavery in the United States, white landowners and planters could no longer legally enslave Black people to work their land. Cotton was still a leading economic commodity, and the newly freed enslaved needed to make a living for themselves. Many turned to the trade that they’d been forced to become familiar with – farming – typically as a sharecropper or a tenant farmer.

Although neither type of farmer possessed an actual farm, the tenant farmer was regarded as a higher-up on the farming food chain. Regardless of race, tenant farmers typically paid a landowner rent for a house and 40 acres of farmland, which included the right to grow crops on it of which they owned and controlled decision-making for. They used their own mules, plow, planter, and family to maintain it. Generally, the landowner received approximately one-fourth of the tenant’s crop and kept the remainder.

On the other hand, sharecroppers generally had fewer resources, including financial. Their situation postured them to make agreements to farm white landowners’ land in exchange for a portion of the crops that they raised. They did not have the equipment or capital and owed their landowner to utilize both. There was no control over the types of crops planted or how they were sold, and the sharecroppers generally only received fifty percent of the crop that they produced. Despite the unfair farming hierarchy, both types of farmers often found themselves in debt to their landowner.

Like many counties and states in the South before the Civil War, a great portion of Phillips County’s land was developed to grow cotton. Thousands of acres of farmland were created and grossly depended on the labor of enslaved Black people to maintain it with little to no rightful compensation. In contrast, their labor created generational wealth for major landowners and planters since cotton was a top commodity well into the 20th century.

Once the Civil War concluded, abolishing the institution of slavery in the United States, white landowners and planters could no longer legally enslave Black people to work their land. Cotton was still a leading economic commodity, and the newly freed enslaved needed to make a living for themselves. Many turned to the trade that they’d been forced to become familiar with – farming – typically as a sharecropper or a tenant farmer.

Although neither type of farmer possessed an actual farm, the tenant farmer was regarded as a higher-up on the farming food chain. Regardless of race, tenant farmers typically paid a landowner rent for a house and 40 acres of farmland, which included the right to grow crops on it of which they owned and controlled decision-making for. They used their own mules, plow, planter, and family to maintain it. Generally, the landowner received approximately one-fourth of the tenant’s crop and kept the remainder.

On the other hand, sharecroppers generally had fewer resources, including financial. Their situation postured them to make agreements to farm white landowners’ land in exchange for a portion of the crops that they raised. They did not have the equipment or capital and owed their landowner to utilize both. There was no control over the types of crops planted or how they were sold, and the sharecroppers generally only received fifty percent of the crop that they produced. Despite the unfair farming hierarchy, both types of farmers often found themselves in debt to their landowner.

PEONAGE

In 1867, Congress passed the Peonage Abolition Act of 1867 to end an employer’s ability to make a worker pay off a debt with work or the systematic indebtedness to employers. However, the practice was still implemented in the Arkansas Delta keeping Black sharecroppers in a continuous position of servitude to the white landowners after the Civil War.

Major landowners and planting companies required farmers to purchase their farming supplies and personal goods from plantation commissaries as a condition to farm on their land. They received doodlum books (or vouchers) to use as credit at the plantation commissaries, whose prices were usually excessively inflated compared to the lower pricing at the town stores. This made it difficult for many to afford the supplies they needed to work and kept them in a continued debt. Most Black sharecroppers had little money after paying their landowners their due if they could pay at all. As a result, many found themselves in debt to not only the landowner but the plantation commissaries, as well.

The abusive profit-sharing arrangements, practices, and prices were a regular cause for conflict between tenants and landowners because it made it impossible for them to get out of debt. As a result, Black tenants and sharecroppers began organizing unions to bargain with landowners for better treatment, pay, and accounting from landowners and were often met with resistance. The same would soon be said about Elaine, Arkansas.

In 1867, Congress passed the Peonage Abolition Act of 1867 to end an employer’s ability to make a worker pay off a debt with work or the systematic indebtedness to employers. However, the practice was still implemented in the Arkansas Delta keeping Black sharecroppers in a continuous position of servitude to the white landowners after the Civil War.

Major landowners and planting companies required farmers to purchase their farming supplies and personal goods from plantation commissaries as a condition to farm on their land. They received doodlum books (or vouchers) to use as credit at the plantation commissaries, whose prices were usually excessively inflated compared to the lower pricing at the town stores. This made it difficult for many to afford the supplies they needed to work and kept them in a continued debt. Most Black sharecroppers had little money after paying their landowners their due if they could pay at all. As a result, many found themselves in debt to not only the landowner but the plantation commissaries, as well.

The abusive profit-sharing arrangements, practices, and prices were a regular cause for conflict between tenants and landowners because it made it impossible for them to get out of debt. As a result, Black tenants and sharecroppers began organizing unions to bargain with landowners for better treatment, pay, and accounting from landowners and were often met with resistance. The same would soon be said about Elaine, Arkansas.

PFHUA

Robert Lee Hill resided in Winchester, Arkansas, in 1917, where he worked for the Valley Planting Company. Familiar with the peonage practices, he wanted to help Black sharecroppers in the Arkansas Delta with legal representation to get fair settlements on their cotton from white landlords. This logic would offer Black sharecroppers a way out of poverty and indebtment to white landowners and give them economic freedom from peonage practices to build and have their own prosperity.

Hill decided to develop an extension of the U.S. Congress’ Colored Union Benevolent Association established in 1865. He and a physician named V.E. Powell called it the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America (PFHUA). They organized and incorporated it in 1918 in Winchester with articles of incorporation drawn up by the law firm of Williamson and Williamson in Monticello, Arkansas of Drew County. Its objective was to “advance the interests of the Negro, morally and intellectually, and to make him a better citizen and a better farmer,” answering the question of why “laborers cannot control their just earnings which they work for.”

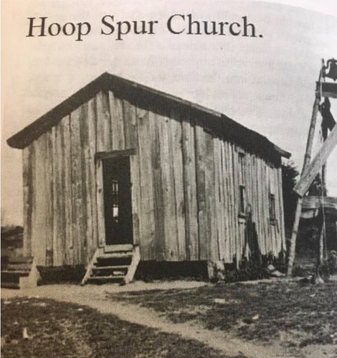

The PFHUA operated similarly to a fraternal and social order as it had passwords, handshakes, and signs that only members knew. It had three lodges – one in Ratio, Elaine, and Hoop Spur, Arkansas, and used “patriotic language” in its literature, including bylaws requiring its member to be upstanding, law-abiding citizens. It had one elected salaried deputy who held office for six months. Members were to purchase a one dollar-share of the organization, which resulted in a capital stock of $1,000 for the joint-stock company and would allow the organization to invest in real estate. Members also collected money to hire legal representation from Ulysses S. Bratton, a white lawyer from Little Rock who won peonage law violation cases, to bring legal charges against their landlords and fight for their share of the cotton crop of 1919.

Robert Lee Hill resided in Winchester, Arkansas, in 1917, where he worked for the Valley Planting Company. Familiar with the peonage practices, he wanted to help Black sharecroppers in the Arkansas Delta with legal representation to get fair settlements on their cotton from white landlords. This logic would offer Black sharecroppers a way out of poverty and indebtment to white landowners and give them economic freedom from peonage practices to build and have their own prosperity.

Hill decided to develop an extension of the U.S. Congress’ Colored Union Benevolent Association established in 1865. He and a physician named V.E. Powell called it the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America (PFHUA). They organized and incorporated it in 1918 in Winchester with articles of incorporation drawn up by the law firm of Williamson and Williamson in Monticello, Arkansas of Drew County. Its objective was to “advance the interests of the Negro, morally and intellectually, and to make him a better citizen and a better farmer,” answering the question of why “laborers cannot control their just earnings which they work for.”

The PFHUA operated similarly to a fraternal and social order as it had passwords, handshakes, and signs that only members knew. It had three lodges – one in Ratio, Elaine, and Hoop Spur, Arkansas, and used “patriotic language” in its literature, including bylaws requiring its member to be upstanding, law-abiding citizens. It had one elected salaried deputy who held office for six months. Members were to purchase a one dollar-share of the organization, which resulted in a capital stock of $1,000 for the joint-stock company and would allow the organization to invest in real estate. Members also collected money to hire legal representation from Ulysses S. Bratton, a white lawyer from Little Rock who won peonage law violation cases, to bring legal charges against their landlords and fight for their share of the cotton crop of 1919.

Progressive steps were underway, and the organization’s reach grew quickly as membership representation encompassed Modoc, Old Town, Ratio, Mellwood, Elaine, Ferguson, and Hoop Spur during the spring of 1919. A contributing factor to the growth was the sentiments of Black sharecroppers who returned from World War I less submissive to Jim Crow mentalities and manipulative practices. They believed that they deserved to and must profit from their cotton crop, not their landlords. This sentiment was shared throughout Arkansas’ Delta, and the organization gained momentum.

Simultaneous to the organization’s progressive efforts of 1919 were labor strikes happening across the nation, causing the government to grow increasingly concerned with the demands of labor in relation to the foundation of the American economy. This period in history is referred to as the Red Scare – a time after the Russian Revolution, Americans feared a labor rebellion, similar to Russia’s, would happen in the United States. As word spread about the PFHUA’s intent for the Delta, the organization became an in-state threat against white supremacy and capitalism for white landowners and white people in general.

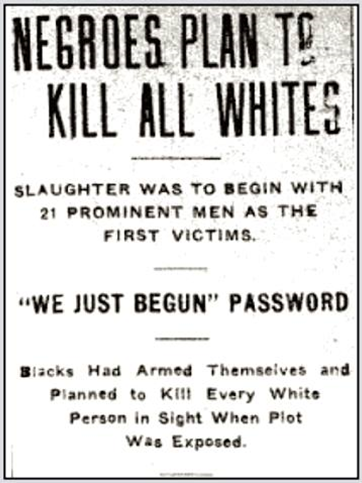

Rumors and lies began to circulate that the PHFUA represented a resistance, with significant backing, that would challenge the white economic and social dominance with violence. The spread of fraudulent information triggered preexisting racial hatreds. The tragedy unfolded in a barbaric method to reverse Black gains.

Simultaneous to the organization’s progressive efforts of 1919 were labor strikes happening across the nation, causing the government to grow increasingly concerned with the demands of labor in relation to the foundation of the American economy. This period in history is referred to as the Red Scare – a time after the Russian Revolution, Americans feared a labor rebellion, similar to Russia’s, would happen in the United States. As word spread about the PFHUA’s intent for the Delta, the organization became an in-state threat against white supremacy and capitalism for white landowners and white people in general.

Rumors and lies began to circulate that the PHFUA represented a resistance, with significant backing, that would challenge the white economic and social dominance with violence. The spread of fraudulent information triggered preexisting racial hatreds. The tragedy unfolded in a barbaric method to reverse Black gains.

Believed to be the church

Believed to be the church

MASSACRE

The PHFUA had held several meetings at their designated locations throughout 1919. On September 30, 1919, it held one at a church that served as a cotton house in Hoop Spur – three miles north of Elaine – where approximately 100 Black people attended. Armed guards surrounded the church to alleviate disruptions or the eavesdropping of white oppression. Suddenly, A shootout commenced between Black PHFUA guards and three white men in front of the church. It was never officially determined who shot first, but Will A. Adkins, a white security officer for the Missouri-Pacific Railroad, was dead, and Charles Pratt, the Phillips County deputy sheriff, was wounded once the gunshots stopped.

A Black, unarmed trustee of Adkins and Pratt named Kid Collins called authorities at a nearby store. The false allegations previously rumored that the PHFUA intended to uprise were contortedly proven true for white residents in the area, and news of the occurrence spread quickly. In the early hours of the morning on October 1, 1919, the Phillips County sheriff deputized white residents to arrest the suspects involved in the Hoop Spur shooting. Although the gang was not met with resistance from any Black residents, they terrorized and murdered several Black people.

Phillips County was saturated with Black people at this time for harvest season, so hundreds of Black sharecroppers were in the area to aid in the labor. They outnumbered whites by a ratio of ten to one. An underlined fear that the Black people would outnumber them encouraged the white rioters to seek help from an estimated 1,000-armed white people from Hoop Spur and surrounding counties in Arkansas and Mississippi, creating a terroristic mob to conspire against an “insurrection.” The gang grew into a mob, and the situation was declared a “race riot,” with Black residents initiating it.

The PHFUA had held several meetings at their designated locations throughout 1919. On September 30, 1919, it held one at a church that served as a cotton house in Hoop Spur – three miles north of Elaine – where approximately 100 Black people attended. Armed guards surrounded the church to alleviate disruptions or the eavesdropping of white oppression. Suddenly, A shootout commenced between Black PHFUA guards and three white men in front of the church. It was never officially determined who shot first, but Will A. Adkins, a white security officer for the Missouri-Pacific Railroad, was dead, and Charles Pratt, the Phillips County deputy sheriff, was wounded once the gunshots stopped.

A Black, unarmed trustee of Adkins and Pratt named Kid Collins called authorities at a nearby store. The false allegations previously rumored that the PHFUA intended to uprise were contortedly proven true for white residents in the area, and news of the occurrence spread quickly. In the early hours of the morning on October 1, 1919, the Phillips County sheriff deputized white residents to arrest the suspects involved in the Hoop Spur shooting. Although the gang was not met with resistance from any Black residents, they terrorized and murdered several Black people.

Phillips County was saturated with Black people at this time for harvest season, so hundreds of Black sharecroppers were in the area to aid in the labor. They outnumbered whites by a ratio of ten to one. An underlined fear that the Black people would outnumber them encouraged the white rioters to seek help from an estimated 1,000-armed white people from Hoop Spur and surrounding counties in Arkansas and Mississippi, creating a terroristic mob to conspire against an “insurrection.” The gang grew into a mob, and the situation was declared a “race riot,” with Black residents initiating it.

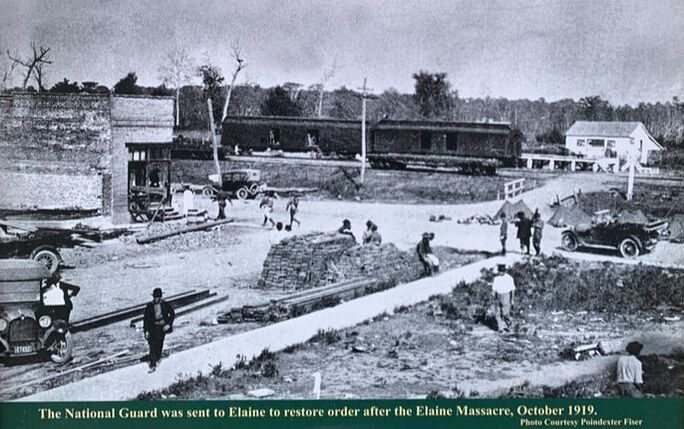

Amid the growing chaos, the Phillips County sheriff sent three telegrams to Governor Charles Hillman Brough – highly unsupportive of anything resembling the Red Scare – requesting he sends U.S. Troops to Elaine to set order. Brough was granted permission by the Department of War in Washington, and Elaine’s active white mob was reinforced with 550 battle-tested soldiers from Camp Pike of North Little Rock the next morning with Brough in tow.

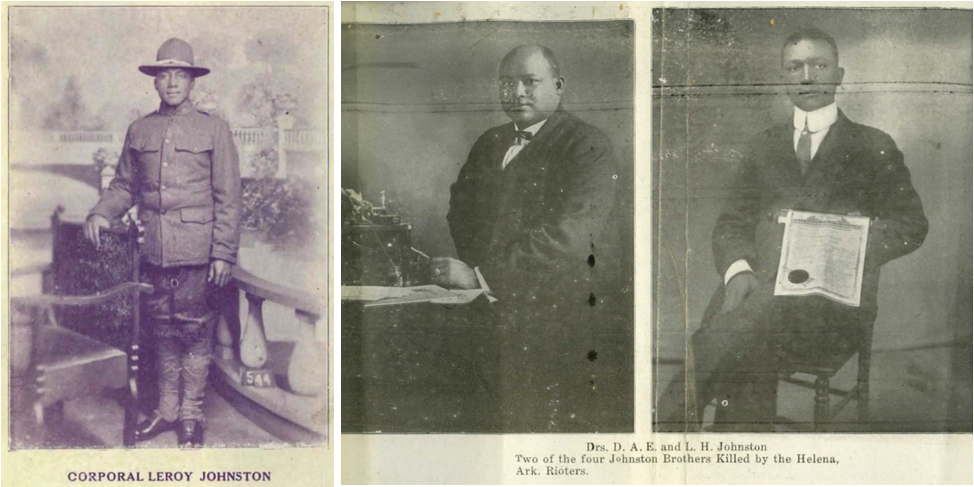

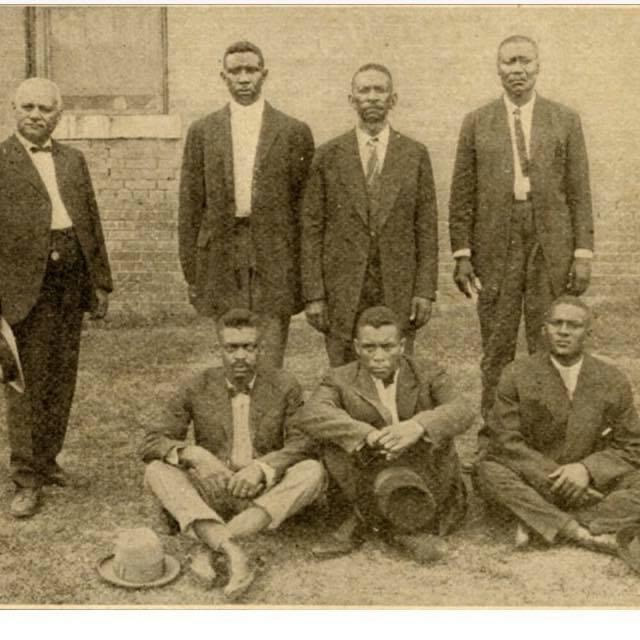

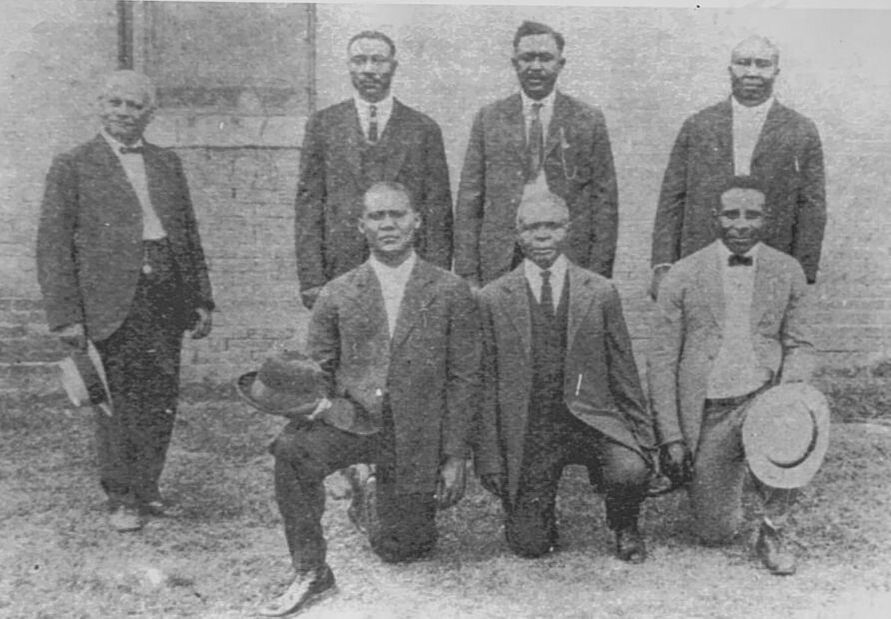

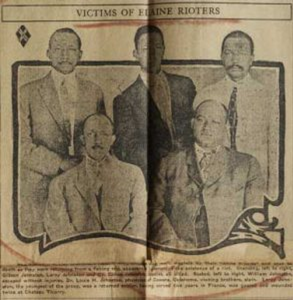

Violence escalated quickly as white terrorists and federal troops scoured and murdered Black men, women, and children in estimates of the hundreds. This number includes David Augustine Elihue (D.A.E.) Johnston, Gibson Allen Johnston, Dr. Lewis Harrison (L. H.) Johnston, and Corporal Leroy Johnston – four brothers of a prominent Black family of Helena who were returning home from a hunting trip. They were not affiliated with the PHFUA or Elaine but were forced from a train and murdered by a white gang member. It is reported that only five white people died from the whole ordeal – Will A. Adkins, Clinton Lee, O. R. Lilly, James A. Tappan, and Corporal Luther D. Earls. All five were seen as heroes that protected the status quo and white supremacy in the region.

Violence escalated quickly as white terrorists and federal troops scoured and murdered Black men, women, and children in estimates of the hundreds. This number includes David Augustine Elihue (D.A.E.) Johnston, Gibson Allen Johnston, Dr. Lewis Harrison (L. H.) Johnston, and Corporal Leroy Johnston – four brothers of a prominent Black family of Helena who were returning home from a hunting trip. They were not affiliated with the PHFUA or Elaine but were forced from a train and murdered by a white gang member. It is reported that only five white people died from the whole ordeal – Will A. Adkins, Clinton Lee, O. R. Lilly, James A. Tappan, and Corporal Luther D. Earls. All five were seen as heroes that protected the status quo and white supremacy in the region.

caption: “[first line unreadable] Standing (l to r): Gibson Johnston, Leroy, Dr. Elihue Johnston, dentist, all killed. Seated (l to r): William Johnson, escaped without injuries, Dr. Lewis H. Johnston, physician of Oklahoma, visiting brothers, slain/ Leroy Johnston, the youngest of the group, was a returned soldier, having served two years in France, was gassed and aoudad twice at Chateau-Thierry. “ Photo courtesy of the Arkansas State Archives.

The massacre did eventually reside on October 4th, and the white mobs returned to their homes leaving hundreds of Black bodies array across the land. Over two hundred surviving Black people were detained and imprisoned until they could be investigated and claimed by their white employers. In the end, the committee charged almost half of them for their alleged role in the riot, murder, and night-riding and accused Robert L. Hill of coercing the PHFUA’s members to stage an insurrection resulting in the subsequent occurrences.

ROBERT L. HILL

Hill and Ocier Bratton, son of Ulysses S. Bratton – unaware of the occurrence in Hoop Spur – took a train to Ratio the morning of October 1 to collect signed retainer agreements and legal fees from Black sharecroppers. When the violence reached them, Bratton was arrested, sent to Helena’s jail in chains for his safety as Phillips County Judge J. M. Jackson feared he would be lynched if he wasn’t. He was released a month later.

Thanks to some friends, Hill was hidden during the massacre and eventually escaped Arkansas completely with the help of a white family. His initial stop was an all-Black community in Boley, Oklahoma, and then South Dakota. His final stop was Topeka, Kansas.

While in Topeka, he sent a letter to a Black Masonic lodge member named Mr. Henderson asking him to bring his wife, Hattie Alexander Hill, and family to him. Mr. Henderson agreed to do so but informed a county sheriff about Hill’s request before he left. Once they arrived in Topeka on January 20, 1920, Robert and Hattie were arrested the same day. Hattie was eventually released from jail, but Hill remained.

Officials wanted to extradite Hill from Kansas for trial in Arkansas, but Henry Justin Allen, the governor of Kansas, refused because he feared Hill would not make it there alive. In October 1920, Hill’s federal charges were dropped, and he was released from jail. He spent the remainder of his life in Topeka, raising his grandson, Robert Lee Hill V, and working at Santa Fe Railway repairing freight cars for a living from 1922 to 1962 under the assumed name of George L. Smith. He died on May 11, 1963.

Hill and Ocier Bratton, son of Ulysses S. Bratton – unaware of the occurrence in Hoop Spur – took a train to Ratio the morning of October 1 to collect signed retainer agreements and legal fees from Black sharecroppers. When the violence reached them, Bratton was arrested, sent to Helena’s jail in chains for his safety as Phillips County Judge J. M. Jackson feared he would be lynched if he wasn’t. He was released a month later.

Thanks to some friends, Hill was hidden during the massacre and eventually escaped Arkansas completely with the help of a white family. His initial stop was an all-Black community in Boley, Oklahoma, and then South Dakota. His final stop was Topeka, Kansas.

While in Topeka, he sent a letter to a Black Masonic lodge member named Mr. Henderson asking him to bring his wife, Hattie Alexander Hill, and family to him. Mr. Henderson agreed to do so but informed a county sheriff about Hill’s request before he left. Once they arrived in Topeka on January 20, 1920, Robert and Hattie were arrested the same day. Hattie was eventually released from jail, but Hill remained.

Officials wanted to extradite Hill from Kansas for trial in Arkansas, but Henry Justin Allen, the governor of Kansas, refused because he feared Hill would not make it there alive. In October 1920, Hill’s federal charges were dropped, and he was released from jail. He spent the remainder of his life in Topeka, raising his grandson, Robert Lee Hill V, and working at Santa Fe Railway repairing freight cars for a living from 1922 to 1962 under the assumed name of George L. Smith. He died on May 11, 1963.

AFTERMATH

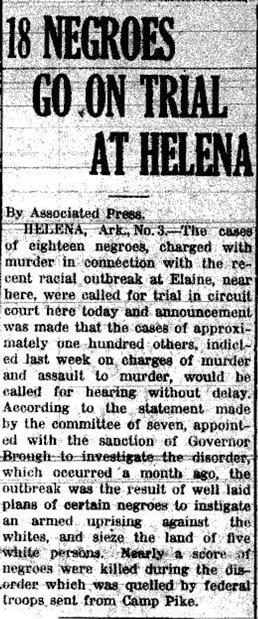

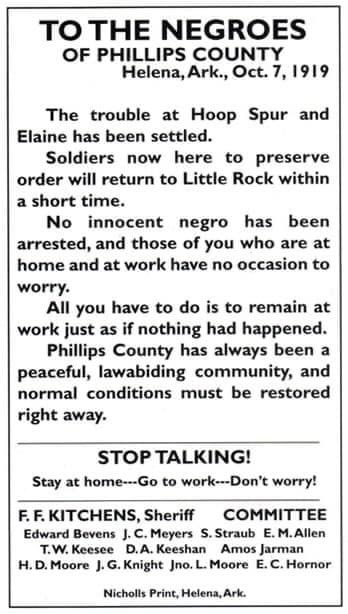

As the massacre was underway, the Phillips County white power structure formed the Committee of Seven to investigate the cause of the events. This committee consisted of white elected officials, businessmen, landowners, and planters. They met with Governor Brough on October 2, and he gave them authoritative clearance in return for agreeance that no lynchings would occur. Within days after September 30, 285 inmates – all Black people – were sent to jail in Helena – a facility only made for a maximum of 48 people.

Upon his return to Little Rock, Brough held a press conference, stating, “The situation at Elaine has been well handled and is absolutely under control. There is no danger of any lynching…. The white citizens of the county deserve unstinting praise for their actions in preventing mob violence.” In many ways, this solidified a biased assumption that Black residents of Elaine (and surrounding areas) were planning an insurrection, which was the cause of the Elaine Massacre. This was the recycled story even in Phillips County.

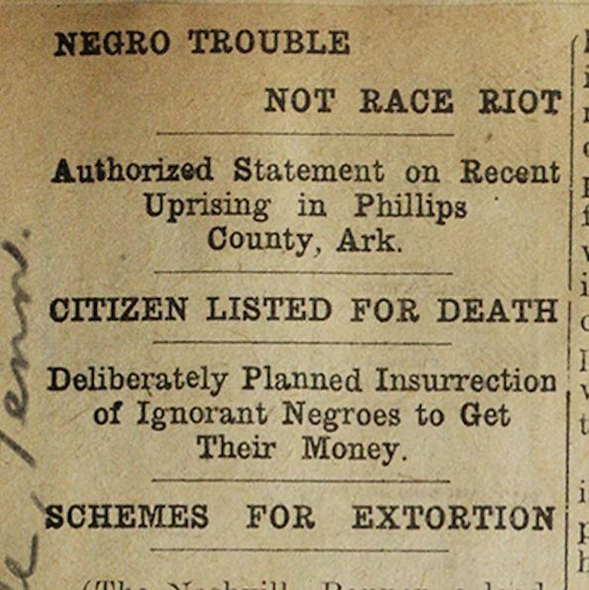

On October 7, E. M. Allen, a planter, real estate developer, and spokesman for the Committee of Seven told the Helena World newspaper that:

As the massacre was underway, the Phillips County white power structure formed the Committee of Seven to investigate the cause of the events. This committee consisted of white elected officials, businessmen, landowners, and planters. They met with Governor Brough on October 2, and he gave them authoritative clearance in return for agreeance that no lynchings would occur. Within days after September 30, 285 inmates – all Black people – were sent to jail in Helena – a facility only made for a maximum of 48 people.

Upon his return to Little Rock, Brough held a press conference, stating, “The situation at Elaine has been well handled and is absolutely under control. There is no danger of any lynching…. The white citizens of the county deserve unstinting praise for their actions in preventing mob violence.” In many ways, this solidified a biased assumption that Black residents of Elaine (and surrounding areas) were planning an insurrection, which was the cause of the Elaine Massacre. This was the recycled story even in Phillips County.

On October 7, E. M. Allen, a planter, real estate developer, and spokesman for the Committee of Seven told the Helena World newspaper that:

“The present trouble with the Negroes in Phillips County is not a race riot. It is a deliberately planned insurrection of the Negroes against the whites directed by an organization known as the ‘Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America,’ established for banding Negroes together for the killing of white people.”

This erroneous claim perpetuated over a century despite evidence that shows white mobs did, in fact, murder Black people in and around Elaine under a false pretense – intentional or otherwise. Many supported this claim back then. It germinated for generations that followed despite evidence and testimonies proving otherwise, including two of Phillips County sheriff’s gang members, T. K. Jones and H. F. Smiddy, admitting to the contrary with signed affidavits in 1921. Also, Ocier Bratton’s later report that Elaine was quiet, and he did not see armed Blacks attacking anyone during his time there.

In addition to these concerns were the operations of Colonel Isaac Jenks, the commander of the U.S. troops at Elaine. In one discrepancy, Jenks sent orders that every human is disarmed in Elaine; however, he and a company of men entered Hoop Spur with at least two machine guns. It is believed that a historically common militia-style method to cease Black revolts was used with several accounts to support this belief, including a Memphis Press correspondent article written on October 2, 1919, stating, “Many Negroes are reported killed by the soldiers….” His corporal, Luther D. Earls, was killed, but Jenks did not mention any shots being fired in his report. He also only reported two Black deaths when a military intelligence reported an estimated 20 black deaths.

In addition to these concerns were the operations of Colonel Isaac Jenks, the commander of the U.S. troops at Elaine. In one discrepancy, Jenks sent orders that every human is disarmed in Elaine; however, he and a company of men entered Hoop Spur with at least two machine guns. It is believed that a historically common militia-style method to cease Black revolts was used with several accounts to support this belief, including a Memphis Press correspondent article written on October 2, 1919, stating, “Many Negroes are reported killed by the soldiers….” His corporal, Luther D. Earls, was killed, but Jenks did not mention any shots being fired in his report. He also only reported two Black deaths when a military intelligence reported an estimated 20 black deaths.

[soldiers in Elaine had ] “committed one murder after another with all the calm deliberation in the world, either too heartless to realize the enormity of their crimes, or too drunk on moonshine to give a continental darn.”

- Sharpe Dunaway, 1925

an employee of the Arkansas Gazette

Another discrepancy that developed was Jenks’ failure to report prisoner torture. Although he sent a detachment company to guard the Helena jail to prevent lynchings, his soldiers still tortured the prisoners to make them confess to planning an insurrection. The military intelligence reports did not include the names of these Black prisoners but that the confessions were made by the imprisoned.

Contrasting these false narratives, biased perspectives of justification, and self-righteous innocence were those of the opposite side who believe that the violence was a response against Black unionization by white landowners. The New York branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) sent Field Secretary Walter White to investigate the incident of Elaine, and he contested the allegations against the Black of Elaine that were permeating America.

Contrasting these false narratives, biased perspectives of justification, and self-righteous innocence were those of the opposite side who believe that the violence was a response against Black unionization by white landowners. The New York branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) sent Field Secretary Walter White to investigate the incident of Elaine, and he contested the allegations against the Black of Elaine that were permeating America.

On October 19, 1919, White wrote the Chicago Daily News that the insurrection of Black people in Elaine was propaganda, “only a figment of the imagination of Arkansas whites and not based on fact. …White men in Helena told me that more than one hundred Negroes were killed.” Inclusive to this is anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s pamphlet entitled “The Arkansas Race Riot.” It is a collection of accounts of torture and desecration endured by the imprisoned that she acquired through secret interviews with them. It, too, serves to challenge all allegations of an insurrection.

Regardless of the false narratives spread from one side and the efforts to disparage them from the other side, hundreds of Black lives were shattered, with families and friends displaced and living in fear. It is believed that jailed sharecroppers were made to sign contingent agreements stating that they would not join any organization – other than church – without getting permission from the white landowner in exchange for their freedom from jail. Women were given the same proposition or an in-house peonage agreement in exchange for their men to be released from jail.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett mentions that many surviving women and children fled to Little Rock and were hidden in the Dunbar community. The community helped raise money to get many of the displaced to Illinois and other areas. They also helped raise money to assist with the legal fees of the massacre-related litigations that would soon follow.

Many Black residents moved out of Arkansas, and some went into hiding to protect loved ones from association with others. The PFHUA quickly dissolved at the conclusion of the massacre, and labor operations reverted to its original peonage practices. Acts of intimidation and white control over Black labor remained a constant in Elaine and surrounding towns. The number of Black lives lost during the Elaine Massacre is yet to be totaled. It is not known where all the Black bodies went, but it is believed that they were included in a mass grave.

Regardless of the false narratives spread from one side and the efforts to disparage them from the other side, hundreds of Black lives were shattered, with families and friends displaced and living in fear. It is believed that jailed sharecroppers were made to sign contingent agreements stating that they would not join any organization – other than church – without getting permission from the white landowner in exchange for their freedom from jail. Women were given the same proposition or an in-house peonage agreement in exchange for their men to be released from jail.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett mentions that many surviving women and children fled to Little Rock and were hidden in the Dunbar community. The community helped raise money to get many of the displaced to Illinois and other areas. They also helped raise money to assist with the legal fees of the massacre-related litigations that would soon follow.

Many Black residents moved out of Arkansas, and some went into hiding to protect loved ones from association with others. The PFHUA quickly dissolved at the conclusion of the massacre, and labor operations reverted to its original peonage practices. Acts of intimidation and white control over Black labor remained a constant in Elaine and surrounding towns. The number of Black lives lost during the Elaine Massacre is yet to be totaled. It is not known where all the Black bodies went, but it is believed that they were included in a mass grave.

TRIAL

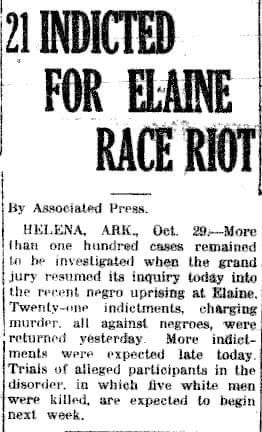

Of the 285 Black people sent to jail in Helena, Phillips County’s grand jury ultimately charged 122 with crimes on October 31, 1919. The initial trials began on November 3 at the Phillips County courthouse with Judge Jackson presiding. In a speedy process, the first twelve of the 285 received the death penalty by electric chair and collectively became known as the Elaine Twelve. They are Frank Moore, Frank and Ed Hicks, Joe Knox, Paul Hall, and Ed Coleman – known as the Moore defendants – and Alfred Banks, Ed Ware, William Wordlaw, Albert Giles, Joe Fox, and John Martin – known as the Ware defendants.

Judge Jackson appointed white attorneys from Helena to the Twelve but did not meet with their counsel prior to or granted permission by their counsel to

defend themselves on the stand. Frank Hicks’ attorney, Jacob Fink, admitted to the jury that he had not interviewed any witnesses, made any motion for a change of venue, or challenged a single prospective juror and just simply took the first twelve prisoners. These were violations of the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment that requires courts had to hear and examine evidence in state criminal cases to ensure that defendants had received due process.

Additional violations of this clause were the location of the trials, the length of time between the trials, and the speed of the trials, all denying the defendants a right to a fair trial. Nevertheless, all twelve men received death penalties on November 5, 1919. After this ruling, sixty-five other imprisoned Black people of the Elaine Massacre quickly entered plea-bargains, accepting 21-year sentences for second-degree murder.

Parallel to this time, the NAACP’s Field Secretary Walter White had returned to New York with reports, and the organization was preparing to help the Elaine Twelve. They hired Black Little Rock attorney Scipio Africanus Jones and white Little Rock attorney George C. Murphy to appeal the Moore defendants’ verdict and serve as the Twelve’s counsel under the recommendation of Ulysses S. Bratton. Murphy brought his junior partner, Edgar L. McHaney, onboard to assist. The Twelve were litigated in two separate groups for several years to come.

Of the 285 Black people sent to jail in Helena, Phillips County’s grand jury ultimately charged 122 with crimes on October 31, 1919. The initial trials began on November 3 at the Phillips County courthouse with Judge Jackson presiding. In a speedy process, the first twelve of the 285 received the death penalty by electric chair and collectively became known as the Elaine Twelve. They are Frank Moore, Frank and Ed Hicks, Joe Knox, Paul Hall, and Ed Coleman – known as the Moore defendants – and Alfred Banks, Ed Ware, William Wordlaw, Albert Giles, Joe Fox, and John Martin – known as the Ware defendants.

Judge Jackson appointed white attorneys from Helena to the Twelve but did not meet with their counsel prior to or granted permission by their counsel to

defend themselves on the stand. Frank Hicks’ attorney, Jacob Fink, admitted to the jury that he had not interviewed any witnesses, made any motion for a change of venue, or challenged a single prospective juror and just simply took the first twelve prisoners. These were violations of the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment that requires courts had to hear and examine evidence in state criminal cases to ensure that defendants had received due process.

Additional violations of this clause were the location of the trials, the length of time between the trials, and the speed of the trials, all denying the defendants a right to a fair trial. Nevertheless, all twelve men received death penalties on November 5, 1919. After this ruling, sixty-five other imprisoned Black people of the Elaine Massacre quickly entered plea-bargains, accepting 21-year sentences for second-degree murder.

Parallel to this time, the NAACP’s Field Secretary Walter White had returned to New York with reports, and the organization was preparing to help the Elaine Twelve. They hired Black Little Rock attorney Scipio Africanus Jones and white Little Rock attorney George C. Murphy to appeal the Moore defendants’ verdict and serve as the Twelve’s counsel under the recommendation of Ulysses S. Bratton. Murphy brought his junior partner, Edgar L. McHaney, onboard to assist. The Twelve were litigated in two separate groups for several years to come.

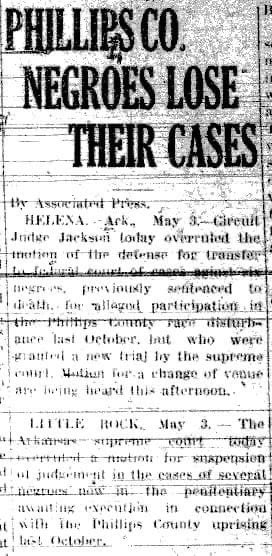

WARE DEFENDANTS

Jones and Murphy were able to secure new trials for the Ware defendants because the trial judge had not required jurors to indicate the degree of murder

on their ballot forms. The Arkansas Supreme Court denied Phillips County’s Judge Jackson of any wrongdoing and officially upheld his verdict on March 29, 1920. However, the charges against the Ware defendants were deemed technically flawed, and the Arkansas Supreme Court granted a new trial.

The retrials began on May 3, 1920, of which time, Murphy became ill, making Jones the lead counsel. He endures some hostility and has to sleep at a different Black family’s house every night out of fear for his life. Unfortunately, Governor Brough held to the six’s death sentences, and the retrial ended in the same verdict. Another appeal was submitted by McHaney.

The prosecution postponed this retrial several times, and it fell outside the legal time allotment stipulations, and in 1923, McHaney submitted an appeal for the Ware defendants to be released. The Arkansas Supreme Court made no move to re-try the men and granted the appeal, and the six were free.

Jones and Murphy were able to secure new trials for the Ware defendants because the trial judge had not required jurors to indicate the degree of murder

on their ballot forms. The Arkansas Supreme Court denied Phillips County’s Judge Jackson of any wrongdoing and officially upheld his verdict on March 29, 1920. However, the charges against the Ware defendants were deemed technically flawed, and the Arkansas Supreme Court granted a new trial.

The retrials began on May 3, 1920, of which time, Murphy became ill, making Jones the lead counsel. He endures some hostility and has to sleep at a different Black family’s house every night out of fear for his life. Unfortunately, Governor Brough held to the six’s death sentences, and the retrial ended in the same verdict. Another appeal was submitted by McHaney.

The prosecution postponed this retrial several times, and it fell outside the legal time allotment stipulations, and in 1923, McHaney submitted an appeal for the Ware defendants to be released. The Arkansas Supreme Court made no move to re-try the men and granted the appeal, and the six were free.

MOORE DEFENDANTS

Jones and Murphy submitted an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court and were denied October 11, 1920, and Governor Thomas McRae set June 10, 1921, as an execution day for the Moore defendants. Sadly, Murphy died of a heart attack on the same day that the appeal was denied. His junior assistant, McHaney, became Jones’ co-counsel.

The Moore defendants were tried for the murder of Clinton Lee. Frank Hicks was accused as the shooter, although the one witness could not identify Hicks as the shooter. The other five were accused of being accessories to the murder the following day. News reports state that the jury only took eight minutes to deliberate before they found Hicks guilty.

Freedom for the Moore defendants was not promising by the summer of 1921. Two days before the six’s execution was to take place, Jones and McHaney used their final option of filing petitions for writs of habeas corpus in the Pulaski County Chancery Court. Unfortunately, U.S. federal district judge Jacob Trieber was not available, so McHaney persuaded Judge John E. Martineau to issue an injunction against the defendants’ executions until a hearing could be held.

Attorney General J. S. Utley immediately dismissed Martineau’s injunction because he had no jurisdiction as he served Pulaski County. Nevertheless, Jones was able to persuade the Arkansas Supreme Court to a hearing for writ of prohibition, which postponed the six’s execution. The hearing was held on June 20, the U.S. Supreme Court denied it on August 4, and a new execution date was set.

The state received a breakthrough on August 30 when two massacre witnesses, T. K. Jones and H. F. Smiddy, changed their testimonies made in the original trial. One admitted to shooting an unarmed Black man, both admitted to torturing Black prisoners in the Helena jail to make them accuse other Black people, and both were also willing to identify other tortures by name.

Jones and Murphy submitted an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court and were denied October 11, 1920, and Governor Thomas McRae set June 10, 1921, as an execution day for the Moore defendants. Sadly, Murphy died of a heart attack on the same day that the appeal was denied. His junior assistant, McHaney, became Jones’ co-counsel.

The Moore defendants were tried for the murder of Clinton Lee. Frank Hicks was accused as the shooter, although the one witness could not identify Hicks as the shooter. The other five were accused of being accessories to the murder the following day. News reports state that the jury only took eight minutes to deliberate before they found Hicks guilty.

Freedom for the Moore defendants was not promising by the summer of 1921. Two days before the six’s execution was to take place, Jones and McHaney used their final option of filing petitions for writs of habeas corpus in the Pulaski County Chancery Court. Unfortunately, U.S. federal district judge Jacob Trieber was not available, so McHaney persuaded Judge John E. Martineau to issue an injunction against the defendants’ executions until a hearing could be held.

Attorney General J. S. Utley immediately dismissed Martineau’s injunction because he had no jurisdiction as he served Pulaski County. Nevertheless, Jones was able to persuade the Arkansas Supreme Court to a hearing for writ of prohibition, which postponed the six’s execution. The hearing was held on June 20, the U.S. Supreme Court denied it on August 4, and a new execution date was set.

The state received a breakthrough on August 30 when two massacre witnesses, T. K. Jones and H. F. Smiddy, changed their testimonies made in the original trial. One admitted to shooting an unarmed Black man, both admitted to torturing Black prisoners in the Helena jail to make them accuse other Black people, and both were also willing to identify other tortures by name.

This information shifted the perspective of all litigations produced from the Elaine Massacre. McHaney reported his findings to the NAACP, and Jones submitted another appeal, but this time with the U.S. Supreme Court. It would be known as Frank Moore et al. v. E. H. Dempsey, Keeper of Arkansas State Penitentiary, or simply Moore vs. Dempsey.

The case was held on September 26 before District Judge J. H. Cottrell. Surprisingly, he treated the alleged facts of the two witnesses as truth but still denied the writs of habeas corpus under the stance that the Arkansas Supreme Court had upheld the original trials as law-abiding and fair. He did, however, allow the NAACP to submit another appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. This time, the Jones and NAACP would not have to prove that the Moore defendants’ allegations were true, but rather the plaintiffs were denied due process and that the state had not corrected the failures from the initial trial.

On January 9, 1923, the President of the NAACP, Moorfield Storey, presented the U.S. Supreme Court new arguments, as well as those of Jones, Murphy, and McHaney in previous appeals; but this time, making sure to mention that a citizen mob dominated the Phillips County trials. The court handed down a 6–2 decision on February 19, 1923, in favor of the Moore defendants stating that the “corrective process afforded to the petitioners…does not seem sufficient” because of the mob dominance. Also, federal judges had jurisdiction to overturn state criminal verdicts to rectify the state's judicial failures, allowing the Moore defendants their constitutional right to due process of law on appeal.

Unfortunately, the case was not over as the court called for a re-hearing in the district court. Jones did not want to have a new hearing, so he entered negotiations in March 1923 so that the Moore defendants could be released from jail. The men had to plead guilty to second-degree murder with a twelve-year sentence. Since the men had already served a third of the sentence, they were eligible for parole. The men agreed, and Governor McRae commuted their death sentences. The Moore defendants were released from jail on January 13, 1925, with indefinite furloughs.

The case was held on September 26 before District Judge J. H. Cottrell. Surprisingly, he treated the alleged facts of the two witnesses as truth but still denied the writs of habeas corpus under the stance that the Arkansas Supreme Court had upheld the original trials as law-abiding and fair. He did, however, allow the NAACP to submit another appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. This time, the Jones and NAACP would not have to prove that the Moore defendants’ allegations were true, but rather the plaintiffs were denied due process and that the state had not corrected the failures from the initial trial.

On January 9, 1923, the President of the NAACP, Moorfield Storey, presented the U.S. Supreme Court new arguments, as well as those of Jones, Murphy, and McHaney in previous appeals; but this time, making sure to mention that a citizen mob dominated the Phillips County trials. The court handed down a 6–2 decision on February 19, 1923, in favor of the Moore defendants stating that the “corrective process afforded to the petitioners…does not seem sufficient” because of the mob dominance. Also, federal judges had jurisdiction to overturn state criminal verdicts to rectify the state's judicial failures, allowing the Moore defendants their constitutional right to due process of law on appeal.

Unfortunately, the case was not over as the court called for a re-hearing in the district court. Jones did not want to have a new hearing, so he entered negotiations in March 1923 so that the Moore defendants could be released from jail. The men had to plead guilty to second-degree murder with a twelve-year sentence. Since the men had already served a third of the sentence, they were eligible for parole. The men agreed, and Governor McRae commuted their death sentences. The Moore defendants were released from jail on January 13, 1925, with indefinite furloughs.

100 YEARS LATER

The massacre gained national attention by being one of the deadliest racial confrontations in Arkansas history. Although the town recently became known as the “Birdhouse Capital of America,” this attribute tends to be overshadowed by the town's history.

Today, there are varying dispositions about the Elaine Massacre from both races. Some prefer the past be left in the past, some want to address and rectify the matter, and some still contend that white residents of and around Phillips County acted appropriately to prevent an insurrection. However, the modern view of most historians – regardless of race – is that a white mob unjustifiably and unnecessarily murdered Black residents of Elaine, the military participated, and government officials in the initial trials allowed it.

A conference was held in 2000 on the matter but resulted in no closure for the people in Phillips County. Several have worked countless hours to ensure the history is not lost and certain narratives are not disregarded. Of those people are the Black and white descendants of the Elaine Massacre. One is Lisa Hicks-Gilbert, a descendant of Frank and Ed Hicks, who moved back to Elaine to do the work.

In 2019, she worked with Clarice and Kwami Abdul-Bey of the Arkansas Peace and Justice Memorial Movement to get Senate Bill 674 passed. This bill proposed the creation of the Unify Arkansas Commission, establishing an official observance of the national day of racial healing in the state, and creating a community remembrance committee in each county in the state. In addition, it requested that Arkansas’ history be a part of the high school and college curriculum, including that of the Elaine Massacre. It also requested the exoneration of 122 Black sharecroppers of the Elaine Massacre because, although it is on record that they were wrongfully charged, the charges have not been dropped.

The massacre gained national attention by being one of the deadliest racial confrontations in Arkansas history. Although the town recently became known as the “Birdhouse Capital of America,” this attribute tends to be overshadowed by the town's history.

Today, there are varying dispositions about the Elaine Massacre from both races. Some prefer the past be left in the past, some want to address and rectify the matter, and some still contend that white residents of and around Phillips County acted appropriately to prevent an insurrection. However, the modern view of most historians – regardless of race – is that a white mob unjustifiably and unnecessarily murdered Black residents of Elaine, the military participated, and government officials in the initial trials allowed it.

A conference was held in 2000 on the matter but resulted in no closure for the people in Phillips County. Several have worked countless hours to ensure the history is not lost and certain narratives are not disregarded. Of those people are the Black and white descendants of the Elaine Massacre. One is Lisa Hicks-Gilbert, a descendant of Frank and Ed Hicks, who moved back to Elaine to do the work.

In 2019, she worked with Clarice and Kwami Abdul-Bey of the Arkansas Peace and Justice Memorial Movement to get Senate Bill 674 passed. This bill proposed the creation of the Unify Arkansas Commission, establishing an official observance of the national day of racial healing in the state, and creating a community remembrance committee in each county in the state. In addition, it requested that Arkansas’ history be a part of the high school and college curriculum, including that of the Elaine Massacre. It also requested the exoneration of 122 Black sharecroppers of the Elaine Massacre because, although it is on record that they were wrongfully charged, the charges have not been dropped.

Awareness of the massacre continues to disseminate through the generations and will potentially be shared in film. In November 2021, Searchlight Pictures announced it acquired the script rights of the book “The Defender” by E. Nicholas Mariani to create a movie about Scipio A. Jones’ role in the Elaine Twelve trials. The movie is set to star Emmy Award-winning actor Sterling K. Brown as Jones.

Frank Moore is buried in the Little Rock’s National Cemetery for his service in WWI. There is an official marker outside the cemetery honoring him.

The centennial of the massacre drew national attention to Elaine. Several efforts have been made to mend the past, such as a dedication memorial in downtown Helena-West Helena erected on September 29, 2019. Also, the Arkansas Civil Rights Heritage Trail in Little Rock memorialized the Elaine Twelve with sidewalk plaques on November 5, 2019. They are located on the River Market’s 300-Block sidewalk, starting in front of the Rev Room. Unfortunately, the attention and mending efforts did not fully resolve the need for community resources such as healthcare services and clean drinking water. The town’s rusted water tower was included in a feature by USA Today in 2021 discussing water contamination in rural communities. Residents have complained about the taste and smell of tap water for years and still do today.

Frank Moore is buried in the Little Rock’s National Cemetery for his service in WWI. There is an official marker outside the cemetery honoring him.

The centennial of the massacre drew national attention to Elaine. Several efforts have been made to mend the past, such as a dedication memorial in downtown Helena-West Helena erected on September 29, 2019. Also, the Arkansas Civil Rights Heritage Trail in Little Rock memorialized the Elaine Twelve with sidewalk plaques on November 5, 2019. They are located on the River Market’s 300-Block sidewalk, starting in front of the Rev Room. Unfortunately, the attention and mending efforts did not fully resolve the need for community resources such as healthcare services and clean drinking water. The town’s rusted water tower was included in a feature by USA Today in 2021 discussing water contamination in rural communities. Residents have complained about the taste and smell of tap water for years and still do today.

TODAY

The city of Elaine continued to grow after the massacre. Even with the constant threats of natural occurrences, such as floods and tornados, the town still progressed. However, it would be the Great Depression that changed the agriculture and timber industries that sparked significant economic hardship and depopulation in Elaine.

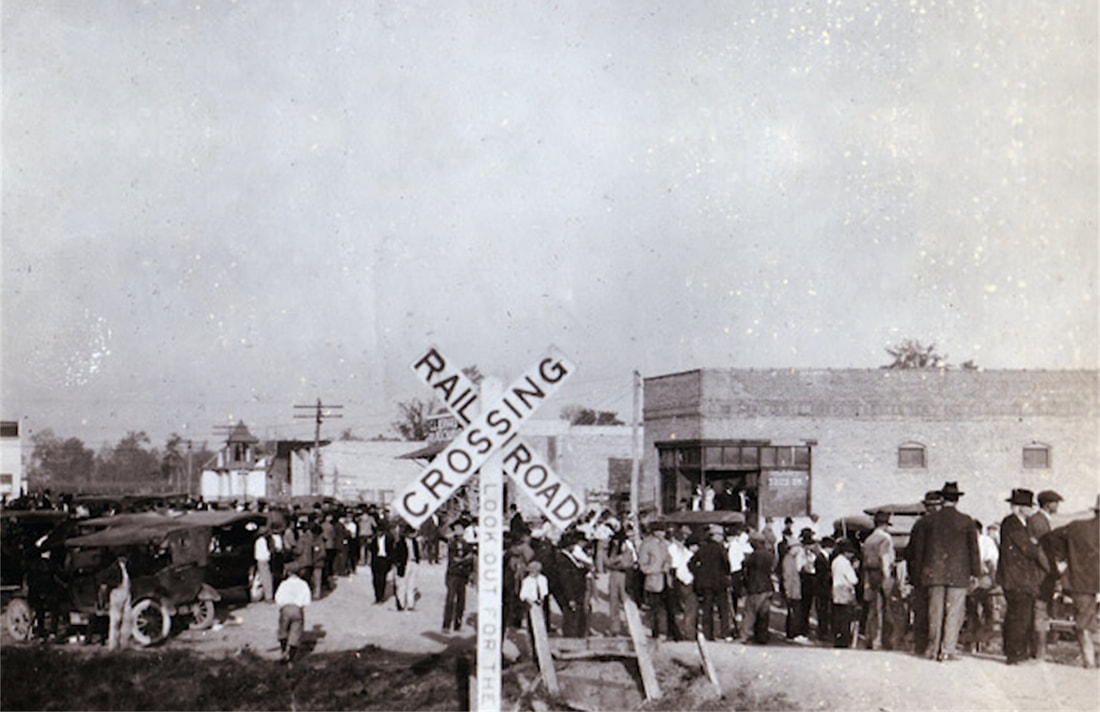

Not much is physically left from the original Elaine of 1919 other than the building located at the corner of Main Street and Quarles Road (Arkansas Highway 44 and 85). The building (pictured here) appears in several pictures taken during the Elaine Massacre and was added to the National Register of Historic Places on February 13, 2020.

From the 1950s until 2010, it operated as the Lee Grocery Store under the operation of the Lee family. The building is believed to have been built in 1915 and, as Lee Grocery Store, was significant for its association with the community in Elaine and eastern Arkansas. It is also an important component of Elaine’s commercial history and cultural influence on the area.

Dr. Mary Olson, a New York native and the founder and president of the Waves of Prayer Ministries, purchased the building in February 2017. She announced plans to restore the building and turn it into a visitor’s center for the Elaine area to memorialize the victims of the Elaine Massacre and the local struggle for civil rights.

The town’s current population is approximately 626.

The city of Elaine continued to grow after the massacre. Even with the constant threats of natural occurrences, such as floods and tornados, the town still progressed. However, it would be the Great Depression that changed the agriculture and timber industries that sparked significant economic hardship and depopulation in Elaine.

Not much is physically left from the original Elaine of 1919 other than the building located at the corner of Main Street and Quarles Road (Arkansas Highway 44 and 85). The building (pictured here) appears in several pictures taken during the Elaine Massacre and was added to the National Register of Historic Places on February 13, 2020.

From the 1950s until 2010, it operated as the Lee Grocery Store under the operation of the Lee family. The building is believed to have been built in 1915 and, as Lee Grocery Store, was significant for its association with the community in Elaine and eastern Arkansas. It is also an important component of Elaine’s commercial history and cultural influence on the area.

Dr. Mary Olson, a New York native and the founder and president of the Waves of Prayer Ministries, purchased the building in February 2017. She announced plans to restore the building and turn it into a visitor’s center for the Elaine area to memorialize the victims of the Elaine Massacre and the local struggle for civil rights.

The town’s current population is approximately 626.