ARKANSAS BLACK HISTORY // Education

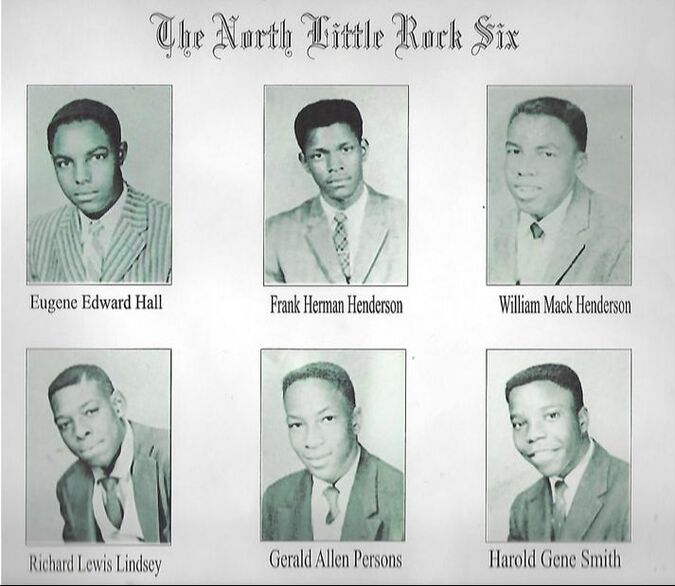

The North Little Rock Six

of Scipio A. Jones High School - Class of 1958

by Dianna Donahue - Aug.01.2021

The Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka U.S. Supreme Court case of 1954 ruled that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional even when equal in quality. As a result, all public schools were to be integrated beginning in September 1957, starting with high schools. The judgment increased the flames of racism across the south. A wave of desegregation and segregation rebellion began as city, state, and school officials were required to implement the change. Several rebellions were documented and publicized for the world to reference for years to come. However, countless rebellions were not, leaving many brave Black students’ stories untold and underrecognized. Among those stories are those of Eugene Hall, Frank Henderson, William Henderson, Richard Lindsey, Gerald Persons, and Harold Smith – the North Little Rock Six.

THE SCHOOL BOARD

North Little Rock school officials of 1954 did not want to change the status quo. Many justified their reasoning with statements, such as: Black schools were just as nice as white schools, Black teachers had more master’s degrees than the white teachers, and the Black facilities were newer and/or newly renovated, so desegregating would offer no advantages. However, their opinions never publicly challenged the Supreme Court’s ruling, and they still prepared to adhere to racial change.

Gov. Orval Faubus’ halt to the integration, plus the segregationist uproar, gave North Little Rock a welcomed excuse to stall the integration process of their schools. The board remained still, not moving on desegregation according to Arkansas law. They saw the Brown vs. Education case decision as a statement of principle rather than a mandate since Faubus halted it, which warranted them no need for immediate action. So they made none.

North Little Rock school officials of 1954 did not want to change the status quo. Many justified their reasoning with statements, such as: Black schools were just as nice as white schools, Black teachers had more master’s degrees than the white teachers, and the Black facilities were newer and/or newly renovated, so desegregating would offer no advantages. However, their opinions never publicly challenged the Supreme Court’s ruling, and they still prepared to adhere to racial change.

Gov. Orval Faubus’ halt to the integration, plus the segregationist uproar, gave North Little Rock a welcomed excuse to stall the integration process of their schools. The board remained still, not moving on desegregation according to Arkansas law. They saw the Brown vs. Education case decision as a statement of principle rather than a mandate since Faubus halted it, which warranted them no need for immediate action. So they made none.

BLACK DELEGATION

A Black delegation developed itself as a result of the board’s stagnation. It was comprised of fifty working-class folk – thirty-one of which were women. Its notion was that North Little Rock did not need to wait to see what other communities in the state would do, and they petitioned the board to desegregate sooner than later. The board’s attorney and municipal judge, Milton McLees, agreed with the delegation’s notion stating that the board’s decision to wait was “premature and unwise.” Nevertheless, he told the delegation that the board would comply “in a spirit of cooperation,” but not until “suggestions for implementing the Supreme Court’s decision…reach North Little Rock from national and state levels.” This response came after the North Side NAACP chapter petitioned for a hearing to discuss desegregation.

To counter McLees’ disposition, a board member discredited the delegation’s relevance in contrast to their petition. It was a general opinion that the delegation was not “a representative group of our educational and civic-minded negro people.” However, it included laborers of the Missouri Pacific Railroad (MoPac) [one primary source of employment in North Little Rock], custodial workers, domestics, and beauticians that lived closed to North Little Rock High and were married. And although NAACP-affiliated attorneys Wiley Branton and George Howard, Jr. of Pine Bluff, and Thaddeus Williams and Jackie Shropshire of Little Rock” were a part of the delegation, it absorbed its gall from its local African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church more than anywhere else. And that was enough.

A Black delegation developed itself as a result of the board’s stagnation. It was comprised of fifty working-class folk – thirty-one of which were women. Its notion was that North Little Rock did not need to wait to see what other communities in the state would do, and they petitioned the board to desegregate sooner than later. The board’s attorney and municipal judge, Milton McLees, agreed with the delegation’s notion stating that the board’s decision to wait was “premature and unwise.” Nevertheless, he told the delegation that the board would comply “in a spirit of cooperation,” but not until “suggestions for implementing the Supreme Court’s decision…reach North Little Rock from national and state levels.” This response came after the North Side NAACP chapter petitioned for a hearing to discuss desegregation.

To counter McLees’ disposition, a board member discredited the delegation’s relevance in contrast to their petition. It was a general opinion that the delegation was not “a representative group of our educational and civic-minded negro people.” However, it included laborers of the Missouri Pacific Railroad (MoPac) [one primary source of employment in North Little Rock], custodial workers, domestics, and beauticians that lived closed to North Little Rock High and were married. And although NAACP-affiliated attorneys Wiley Branton and George Howard, Jr. of Pine Bluff, and Thaddeus Williams and Jackie Shropshire of Little Rock” were a part of the delegation, it absorbed its gall from its local African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church more than anywhere else. And that was enough.

PROMPT AND REASONABLE

By the end of the 1955 school year, no Black enrollment applications were submitted, and desegregating North Little Rock schools had still not started. The board was in no rush, taking full advantage of the natural division between residential areas of the races. Superintendent C.S. Blackburn stated, “in North Little Rock, no school is to permit the attendance of a student who does not live in its attendance zone. And no Negro lives in the attendance zone of a white school.”

Aware of many school boards’ manipulative measures, the U.S. Supreme Court mandated schools to make “a prompt and reasonable start” towards desegregation. The board held one special meeting with local Black educators and NAACP representatives to address the “problems” with integration and discuss whether, to begin with seniors or first-graders, reframing from the NAACP’s request to the desegregation process immediately and comprehensively. By the end of the meeting, the board unanimously reached an agreement.

During a news conference, the board revealed its final integration plan for 1957: integration “would be based on residential zoning, would apply only to twelfth graders, would not extend downwards at the rate of one grade a year without a review of its first year of implementation, and would allow a student to transfer to a school where their race was in the majority.” It requested the plans “be received, if not with favor, with forbearance, tolerance, and understanding.” Many segregationists began to organize, convene, and publicly campaign against integration; however, the next couple of years went off without significant occurrence.

As September 1957 approached, the board did not see integration creating a violent issue as it had for Little Rock Central High School. Only about twenty-eight Black students were even eligible to move to North Little Rock High, and it was assumed that only a few of those twenty-eight would leave their familiarities. So the board did not prepare for any form of occurrence even after Mayor Almon C. Perry suggesting that the National Guard be present. North Little Rock police officers were expected to be on the campus, but only to advert potential violence – not to prevent Black students from entering.

Aware of many school boards’ manipulative measures, the U.S. Supreme Court mandated schools to make “a prompt and reasonable start” towards desegregation. The board held one special meeting with local Black educators and NAACP representatives to address the “problems” with integration and discuss whether, to begin with seniors or first-graders, reframing from the NAACP’s request to the desegregation process immediately and comprehensively. By the end of the meeting, the board unanimously reached an agreement.

During a news conference, the board revealed its final integration plan for 1957: integration “would be based on residential zoning, would apply only to twelfth graders, would not extend downwards at the rate of one grade a year without a review of its first year of implementation, and would allow a student to transfer to a school where their race was in the majority.” It requested the plans “be received, if not with favor, with forbearance, tolerance, and understanding.” Many segregationists began to organize, convene, and publicly campaign against integration; however, the next couple of years went off without significant occurrence.

As September 1957 approached, the board did not see integration creating a violent issue as it had for Little Rock Central High School. Only about twenty-eight Black students were even eligible to move to North Little Rock High, and it was assumed that only a few of those twenty-eight would leave their familiarities. So the board did not prepare for any form of occurrence even after Mayor Almon C. Perry suggesting that the National Guard be present. North Little Rock police officers were expected to be on the campus, but only to advert potential violence – not to prevent Black students from entering.

THE SIX

The board prepared to execute the plan beginning the second week of September, but it was abruptly stopped when Governor Faubus placed the National Guard around Little Rock Central High School on September 2, 1957. Without waiting to see the outcomes of Little Rock’s events, the North Little Rock school board publicly decided that due to “the uncertainty and confusion which now surrounds any plan the Board may attempt to implement at the present time,” they were pausing integration indefinitely or until it could be managed “orderly and peaceably.” Black students intending to enroll at North Little Rock High were to report to Scipio A. Jones High – North Little Rock’s Black high school.

The board assumed that their decision to postpone, plus the events in Little Rock, were enough to persuade Black students to wait out the results of the matter and reframe from integrating at that time. But members of the Black North Little Rock community saw no reason not to just because Governor Faubus halted the Little Rock students.

With only the support of their parents and accompanied by four A.M.E. ministers, the six young Black men walked up the steps of North Little Rock High School, unprotected, on September 9, 1957 – the first day of school. Their names are Eugene Hall, Frank Henderson, William Henderson (unrelated), Richard Lindsey, Gerald Persons, and Harold Smith. The ministers with them were Daniel J. Webster, Fred D. Gipson, John H. Gipson, Walter B. Banks, and two white clerics who chose not to identify themselves.

The board prepared to execute the plan beginning the second week of September, but it was abruptly stopped when Governor Faubus placed the National Guard around Little Rock Central High School on September 2, 1957. Without waiting to see the outcomes of Little Rock’s events, the North Little Rock school board publicly decided that due to “the uncertainty and confusion which now surrounds any plan the Board may attempt to implement at the present time,” they were pausing integration indefinitely or until it could be managed “orderly and peaceably.” Black students intending to enroll at North Little Rock High were to report to Scipio A. Jones High – North Little Rock’s Black high school.

The board assumed that their decision to postpone, plus the events in Little Rock, were enough to persuade Black students to wait out the results of the matter and reframe from integrating at that time. But members of the Black North Little Rock community saw no reason not to just because Governor Faubus halted the Little Rock students.

With only the support of their parents and accompanied by four A.M.E. ministers, the six young Black men walked up the steps of North Little Rock High School, unprotected, on September 9, 1957 – the first day of school. Their names are Eugene Hall, Frank Henderson, William Henderson (unrelated), Richard Lindsey, Gerald Persons, and Harold Smith. The ministers with them were Daniel J. Webster, Fred D. Gipson, John H. Gipson, Walter B. Banks, and two white clerics who chose not to identify themselves.

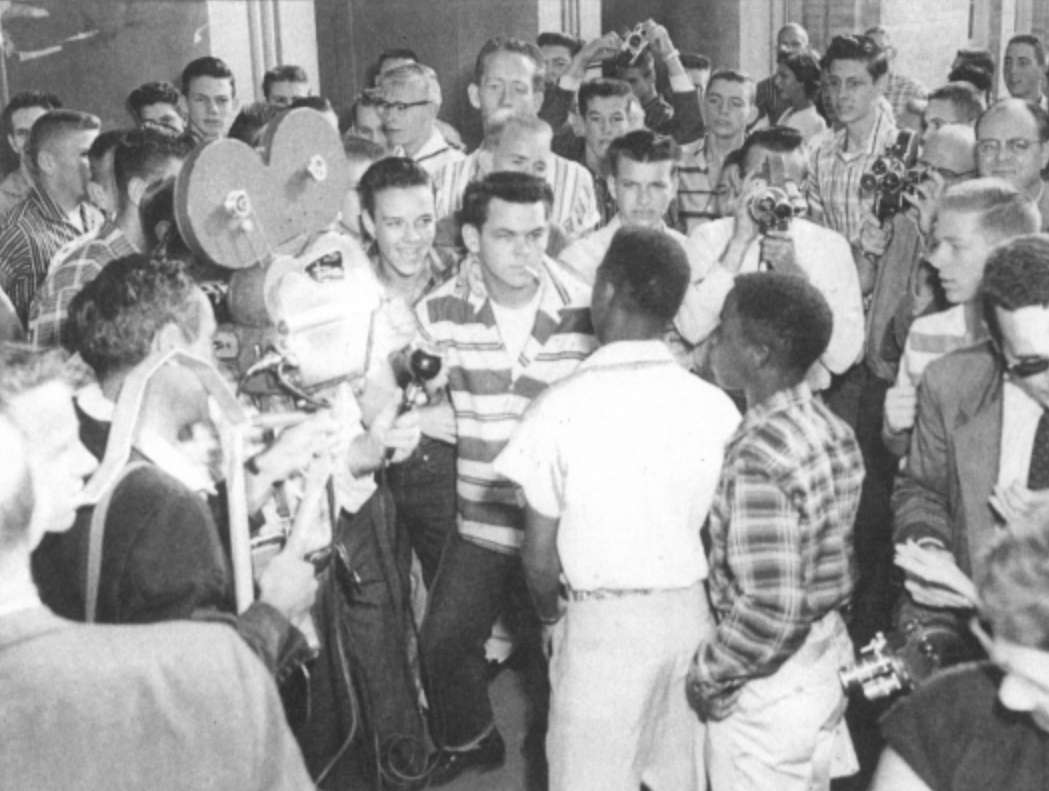

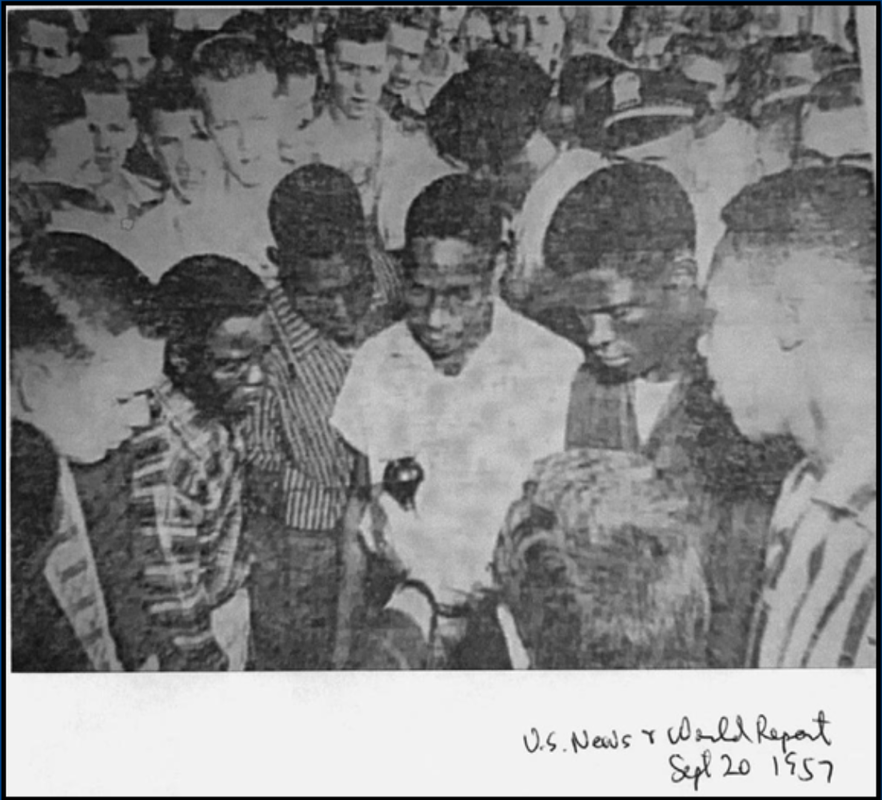

The young men walked approximately eight blocks to the high school and were met by ten angry white students at the steps with around 200 onlooking segregationists name-calling in proximity. The young men continued to walk towards the front door, shoved away twice by adults and students once they got there. The recently elected superintendent, Frederick Bruce Wright, and Principal George Miller came out to redirect the energy and intervene, asking the boys to come in to talk.

Unfortunately, they never made it inside the building because the crowd blocked the entrance and refused to move. The superintendent, too, became entangled in the crowd and unable to get back into the school. There were no physical injuries or altercations; however, two young white men were detained by North Little Rock police long enough to “cool off.”

The Six were instructed to meet Superintendent Wright at the school administration building at 28th and Popular streets for their conference. During the meeting, Superintendent Wright advised the Six to enroll in Scipio Jones High School because he didn’t think integration would work at that time. The Six complied, and the board unanimously decided days later to avoid race-mixing indefinitely.

Unfortunately, they never made it inside the building because the crowd blocked the entrance and refused to move. The superintendent, too, became entangled in the crowd and unable to get back into the school. There were no physical injuries or altercations; however, two young white men were detained by North Little Rock police long enough to “cool off.”

The Six were instructed to meet Superintendent Wright at the school administration building at 28th and Popular streets for their conference. During the meeting, Superintendent Wright advised the Six to enroll in Scipio Jones High School because he didn’t think integration would work at that time. The Six complied, and the board unanimously decided days later to avoid race-mixing indefinitely.

THE VILLAGE

The school board and school administrators were surprised to discover that neither the national NAACP, a local chapter of it, nor Daisy Bates had any part in the Six’s decision. Instead, North Little Rock’s first metaphorical and literal steps toward educational equality were sponsored by a delegation of local working-class Black people, their children, and local A.M.E. clergy. Inclusive to this were teachers at Scipio A. Jones High School, the Six’s original school, who were prepared to help with tutoring if needed.

North Little Rock’s Black community gained much of its tenacity from the local A.M.E. Church rather than national organizations and public figures. No one had instigated or egged on the young men to register or attempt to enter North Little Rock High School. They simply did what their elders told them to do; however, they understood its importance – equal opportunity.

“Wow, there was nothing heroic about what we did. We did what we were told because we’re kids, and it was 1957,” said Richard Lindsey. Gerald Persons told an Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reporter fifty years later, “I knew what we would be facing…But we couldn’t say we couldn’t go if we didn’t try.” Harold Smith said, “It was an effort on our part to integrate, even though we had no court order in North Little Rock. In a sense, we were hopeful we could go, but if not, we understood the situation, and if it didn’t transpire, we would keep trying.”

The four Black A.M.E. ministers that escorted the Six to the school were prepared to take a public stand against segregation and were supported by their Bishop, Odie Sherman – instrumental in inspiring the Six to make their bold move. Minister W. B. Banks was the father of a seventh registrant who happened to be working when the other six made history. He stated years later, “We felt like since they were our children, and it was worth the effort to integrate, we would give them our moral support.” John Gipson felt “They [the Six] did not represent any group and that no group inspired him [to escort]…I [just] thought it was time for the ministers to give leadership to the people.” Another minister, D. J. Webster, told the press, “Just for the record, the NAACP gave absolutely no instructions to us or the students. This move was ours alone. Our responsibility is more than just preaching on Sundays. There were no Uncle Toms.”

Shortly after the occurrence, Rev. Banks called the Six’s act “a local matter” in response to a reporter’s question as to whether their legal actions will include outside interests. He said that the ministers and the parents of the students would be filing a lawsuit in the Federal District Court to force integration, but a suit was never filed. Without the financial means and legal resources of organizations like the NAACP, it was difficult for the Black, working-class community to secure their own successes in the 1950s. Underwriting a case against the North Little Rock school board for not integrating in September 1957 was one of those instances.

The school board and school administrators were surprised to discover that neither the national NAACP, a local chapter of it, nor Daisy Bates had any part in the Six’s decision. Instead, North Little Rock’s first metaphorical and literal steps toward educational equality were sponsored by a delegation of local working-class Black people, their children, and local A.M.E. clergy. Inclusive to this were teachers at Scipio A. Jones High School, the Six’s original school, who were prepared to help with tutoring if needed.

North Little Rock’s Black community gained much of its tenacity from the local A.M.E. Church rather than national organizations and public figures. No one had instigated or egged on the young men to register or attempt to enter North Little Rock High School. They simply did what their elders told them to do; however, they understood its importance – equal opportunity.

“Wow, there was nothing heroic about what we did. We did what we were told because we’re kids, and it was 1957,” said Richard Lindsey. Gerald Persons told an Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reporter fifty years later, “I knew what we would be facing…But we couldn’t say we couldn’t go if we didn’t try.” Harold Smith said, “It was an effort on our part to integrate, even though we had no court order in North Little Rock. In a sense, we were hopeful we could go, but if not, we understood the situation, and if it didn’t transpire, we would keep trying.”

The four Black A.M.E. ministers that escorted the Six to the school were prepared to take a public stand against segregation and were supported by their Bishop, Odie Sherman – instrumental in inspiring the Six to make their bold move. Minister W. B. Banks was the father of a seventh registrant who happened to be working when the other six made history. He stated years later, “We felt like since they were our children, and it was worth the effort to integrate, we would give them our moral support.” John Gipson felt “They [the Six] did not represent any group and that no group inspired him [to escort]…I [just] thought it was time for the ministers to give leadership to the people.” Another minister, D. J. Webster, told the press, “Just for the record, the NAACP gave absolutely no instructions to us or the students. This move was ours alone. Our responsibility is more than just preaching on Sundays. There were no Uncle Toms.”

Shortly after the occurrence, Rev. Banks called the Six’s act “a local matter” in response to a reporter’s question as to whether their legal actions will include outside interests. He said that the ministers and the parents of the students would be filing a lawsuit in the Federal District Court to force integration, but a suit was never filed. Without the financial means and legal resources of organizations like the NAACP, it was difficult for the Black, working-class community to secure their own successes in the 1950s. Underwriting a case against the North Little Rock school board for not integrating in September 1957 was one of those instances.

END RESULTS

Within a couple of days after the occurrence, the Six’s integration attempt became a significantly symbolic gesture of equality for the city instead of reality. The Six did not attempt to integrate North Little Rock High School again but instead returned to Scipio A. Jones High School by September 23, where they all graduated in 1958.

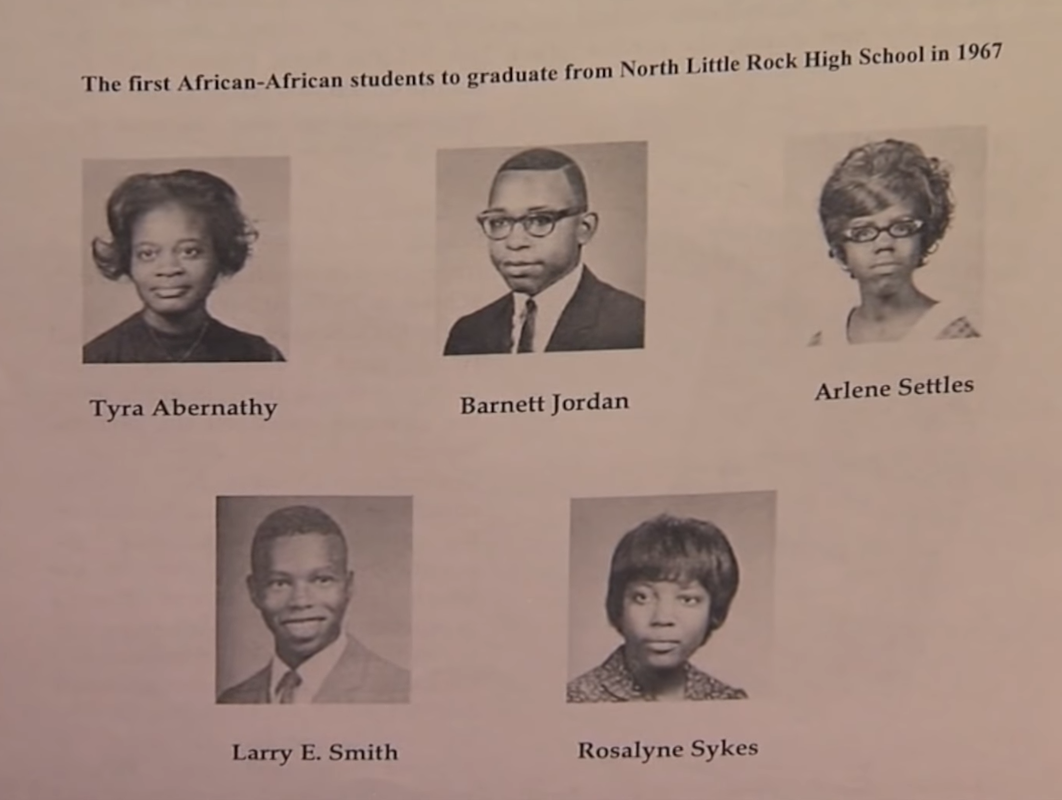

Five Black students tried to register for North Little Rock classes in 1963, but the board denied their applications. It did not integrate its schools until 1964, and alternatively beginning with first- and second-graders instead of the twelfth as it originally arranged. Eight Black first- and second-graders desegregated Clendenin and Riverside elementary schools on September 3, 1964. Twenty Black students entered North Little Rock High School on September 6, 1966, with five of them graduating in 1967, becoming the school’s first Black graduating students. They are Tyra Abernathy, Barnett Jordan, Arlene Settles, Larry E. Smith, and Rosalyne Sykes. Complete integration did not happen until 1972 when school busing was introduced to the city.

Within a couple of days after the occurrence, the Six’s integration attempt became a significantly symbolic gesture of equality for the city instead of reality. The Six did not attempt to integrate North Little Rock High School again but instead returned to Scipio A. Jones High School by September 23, where they all graduated in 1958.

Five Black students tried to register for North Little Rock classes in 1963, but the board denied their applications. It did not integrate its schools until 1964, and alternatively beginning with first- and second-graders instead of the twelfth as it originally arranged. Eight Black first- and second-graders desegregated Clendenin and Riverside elementary schools on September 3, 1964. Twenty Black students entered North Little Rock High School on September 6, 1966, with five of them graduating in 1967, becoming the school’s first Black graduating students. They are Tyra Abernathy, Barnett Jordan, Arlene Settles, Larry E. Smith, and Rosalyne Sykes. Complete integration did not happen until 1972 when school busing was introduced to the city.

RECOGNITION

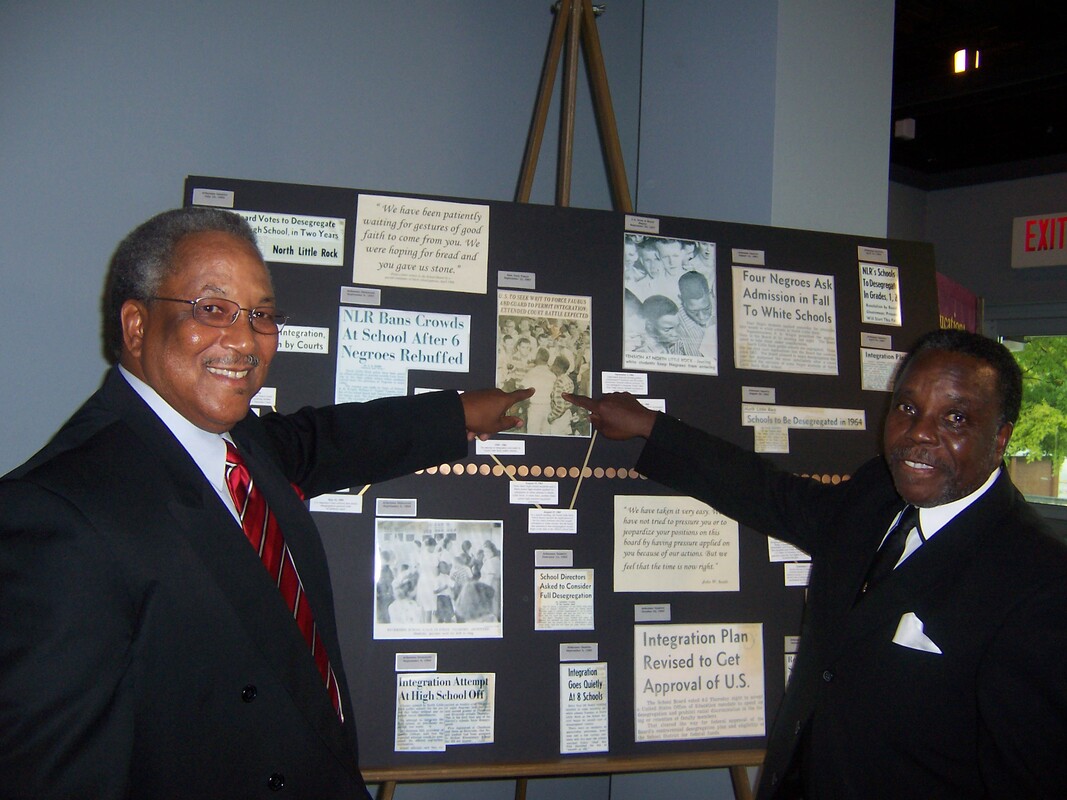

On September 9, 2007, the STAND Foundation and the City of North Little Rock hosted a ceremony to honor the six men on the 50th anniversary of their attempt to integrate North Little Rock High School. During the celebration, the three walked up the front steps of North Little Rock High School and through the front door.

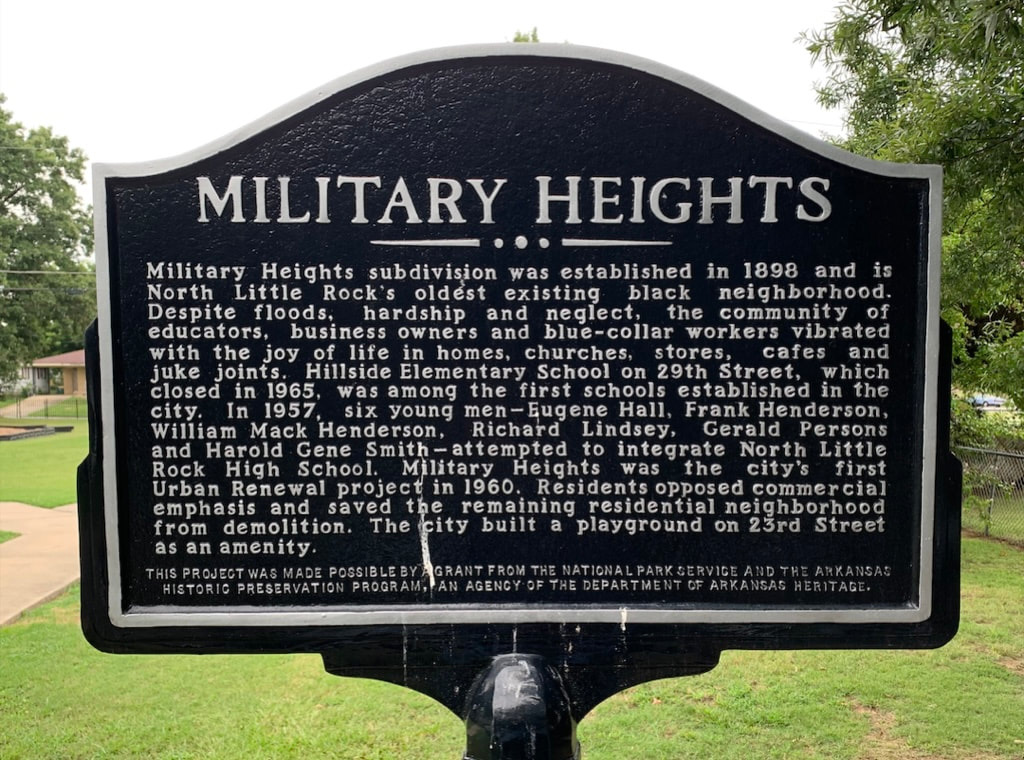

Recognition became more regular after this. Richard Lindsey stated that former President Bill Clinton honored them and that he was given a plaque from state legislatures celebrating their bravery. The Arkansas Legislature also passed a resolution honoring “the courage and the dignity of the North Little Rock Six and their families” on February 11, 2019. There is also a sign erect at Military Heights Park of North Little Rock honoring the six young men.

Prior to this, the six young men did not receive much recognition for their efforts that day because the world was watching Little Rock Central High School. “It was over for the next 50 years, as far as North Little Rock is concerned…Central took over, and North Little Rock never existed…it never came up, and not that much written or spoken about it. The newspaper did their daily thing. We were considered not important for 50 years,” said Richard Lindsey.

The New York Times did, however, feature a front-page photograph of Gerald Persons and Harold Smith. The picture captured a white youth, with a cigarette planted in his mouth, positioned to push Smith and Persons away from the school’s entrance. Unfortunately, the photo is misidentified as an occurrence at Little Rock Central High School.

TODAY

There are three surviving North Little Rock 6, and of those three, Richard Lindsey (of the Lindsey Barbecue family) is the only one that resides in North Little Rock.

On September 9, 2007, the STAND Foundation and the City of North Little Rock hosted a ceremony to honor the six men on the 50th anniversary of their attempt to integrate North Little Rock High School. During the celebration, the three walked up the front steps of North Little Rock High School and through the front door.

Recognition became more regular after this. Richard Lindsey stated that former President Bill Clinton honored them and that he was given a plaque from state legislatures celebrating their bravery. The Arkansas Legislature also passed a resolution honoring “the courage and the dignity of the North Little Rock Six and their families” on February 11, 2019. There is also a sign erect at Military Heights Park of North Little Rock honoring the six young men.

Prior to this, the six young men did not receive much recognition for their efforts that day because the world was watching Little Rock Central High School. “It was over for the next 50 years, as far as North Little Rock is concerned…Central took over, and North Little Rock never existed…it never came up, and not that much written or spoken about it. The newspaper did their daily thing. We were considered not important for 50 years,” said Richard Lindsey.

The New York Times did, however, feature a front-page photograph of Gerald Persons and Harold Smith. The picture captured a white youth, with a cigarette planted in his mouth, positioned to push Smith and Persons away from the school’s entrance. Unfortunately, the photo is misidentified as an occurrence at Little Rock Central High School.

TODAY

There are three surviving North Little Rock 6, and of those three, Richard Lindsey (of the Lindsey Barbecue family) is the only one that resides in North Little Rock.