ARKANSAS BLACK HISTORY // Building

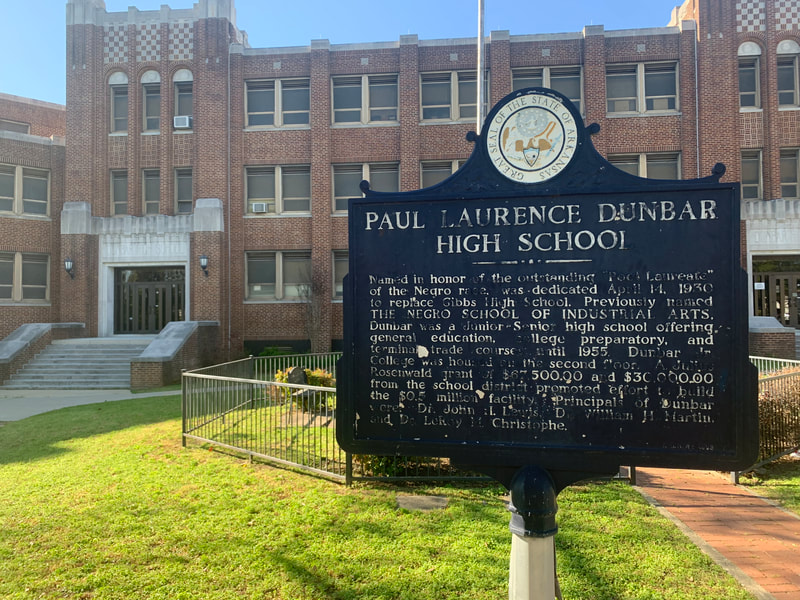

Paul Laurence Dunbar High School

The Architectural Showpiece of the Negro Neighborhood

by Dianna Donahue - Apr.01.2021

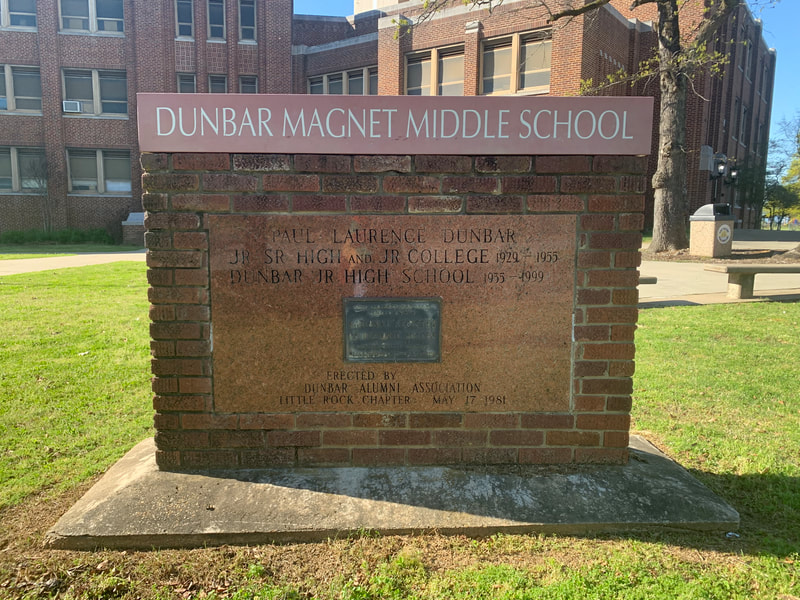

Little Rock’s Dunbar Middle School has a rich historical significance to the progression of Black people in Arkansas in four areas: African-American history, education history, legal history, and architecture/engineering achievement. Under its educational operations as Paul Laurence Dunbar Junior and Senior High School and Junior College, it offered a complete, extensive academic and vocational education to Black students.

Dunbar was the only educational institute that Black students could attend in Little Rock because of legal segregation laws. Its construction was a part of a comprehensive program to improve the quality of public education for Black people in the early 1900s, including 338 schools built in Arkansas largely funded by the then president of Sears, Roebuck, and Company, Julius Rosenwald. Students would walk as far as today’s Arch Street to attend in both winter and spring to take part in Dunbar's educational opportunities and experiences.

Located at the corner of Wright Avenue and Ringo Street, with its elaborate art deco-style brick patterns and subtle towers complimented by the stoops underneath them, Paul Laurence Dunbar Junior and Senior High School and Junior College was the architectural showcase of the Black neighborhood. With its advanced curriculum and perseverance of excellence, it was also the neighborhood’s beacon of pride.

Dunbar was the only educational institute that Black students could attend in Little Rock because of legal segregation laws. Its construction was a part of a comprehensive program to improve the quality of public education for Black people in the early 1900s, including 338 schools built in Arkansas largely funded by the then president of Sears, Roebuck, and Company, Julius Rosenwald. Students would walk as far as today’s Arch Street to attend in both winter and spring to take part in Dunbar's educational opportunities and experiences.

Located at the corner of Wright Avenue and Ringo Street, with its elaborate art deco-style brick patterns and subtle towers complimented by the stoops underneath them, Paul Laurence Dunbar Junior and Senior High School and Junior College was the architectural showcase of the Black neighborhood. With its advanced curriculum and perseverance of excellence, it was also the neighborhood’s beacon of pride.

picture source: https://lrculturevulture.com/2016/02/12/black-history-spotlight-dunbar-historic-neighborhood/

picture source: https://lrculturevulture.com/2016/02/12/black-history-spotlight-dunbar-historic-neighborhood/

HISTORIC DISTRICT

The Paul Laurence Dunbar School Neighborhood Historic District is located in the southern part of the downtown Little Rock area. This district represents the evolution of an integrated Black, working, middle-class neighborhood of the late-nineteenth century to a predominantly Black working, middle-class neighborhood of the 1960s.

The District is a neighboring area and contributing success factor to the once flourishing West 9th Street Black Business District of downtown Little Rock. It was comprised of Black, educated business owners and professionals who could afford to purchase, remodel, or build their homes and contribute to the sustainability of the community.

The first home of the district was constructed in 1890, with additional homes built through 1961. Three of the residential properties within the District are listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 28, 1999 - the Scipio A. Jones 1) House at 1872 Cross Street built in 1928, the Miller House(2) at 1853 Ringo Street built in 1906 and remodeled in 1924, and the Womack House(3) at 1867 Ringo Street built in 1922. Each one is a Craftsman-style structure with its own flare. The Arkansas Historic Preservation Program says that the homes' architectural styles within the District exhibit influences and variants of a broad mix of popular trends of the time. They also show evidence that the Black residents of the area were resourceful and growing in prosperity despite segregation.

The District includes 155 properties varying in architectural styles that show a collective entity through the neighborhood to represent its evolution. Although the District is abundant with historic resources, it is distressed with blight and disinvestment, earning it a place on Arkansas’s most endangered historic place list. The City of Little Rock published its Citywide Historic Preservation Plan in 2009 that would “preserve, maintain and enhance the city’s large stock of historic buildings both downtown and in center-city neighborhoods.” After an intensive architectural survey of the District’s neighborhoods, it was determined that the entire district was historic and was added to the National Register of Historic Places list on September 27, 2013.

According to the National Park Service of the U.S. Department of the Interior, the District is roughly bounded by Wright Avenue on the north, South Chester on the east, South Ringo Street on the west, and West 24th Street on the south. This approximate area sits between the Governor’s Mansion, Little Rock Central High School, and Philander Smith College along Wright Avenue. The District was built on the significance of progression, ethnic heritage, and education. Paul Laurence Dunbar Junior and Senior High School and Junior College became the visual, architectural proof.

The Paul Laurence Dunbar School Neighborhood Historic District is located in the southern part of the downtown Little Rock area. This district represents the evolution of an integrated Black, working, middle-class neighborhood of the late-nineteenth century to a predominantly Black working, middle-class neighborhood of the 1960s.

The District is a neighboring area and contributing success factor to the once flourishing West 9th Street Black Business District of downtown Little Rock. It was comprised of Black, educated business owners and professionals who could afford to purchase, remodel, or build their homes and contribute to the sustainability of the community.

The first home of the district was constructed in 1890, with additional homes built through 1961. Three of the residential properties within the District are listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 28, 1999 - the Scipio A. Jones 1) House at 1872 Cross Street built in 1928, the Miller House(2) at 1853 Ringo Street built in 1906 and remodeled in 1924, and the Womack House(3) at 1867 Ringo Street built in 1922. Each one is a Craftsman-style structure with its own flare. The Arkansas Historic Preservation Program says that the homes' architectural styles within the District exhibit influences and variants of a broad mix of popular trends of the time. They also show evidence that the Black residents of the area were resourceful and growing in prosperity despite segregation.

The District includes 155 properties varying in architectural styles that show a collective entity through the neighborhood to represent its evolution. Although the District is abundant with historic resources, it is distressed with blight and disinvestment, earning it a place on Arkansas’s most endangered historic place list. The City of Little Rock published its Citywide Historic Preservation Plan in 2009 that would “preserve, maintain and enhance the city’s large stock of historic buildings both downtown and in center-city neighborhoods.” After an intensive architectural survey of the District’s neighborhoods, it was determined that the entire district was historic and was added to the National Register of Historic Places list on September 27, 2013.

According to the National Park Service of the U.S. Department of the Interior, the District is roughly bounded by Wright Avenue on the north, South Chester on the east, South Ringo Street on the west, and West 24th Street on the south. This approximate area sits between the Governor’s Mansion, Little Rock Central High School, and Philander Smith College along Wright Avenue. The District was built on the significance of progression, ethnic heritage, and education. Paul Laurence Dunbar Junior and Senior High School and Junior College became the visual, architectural proof.

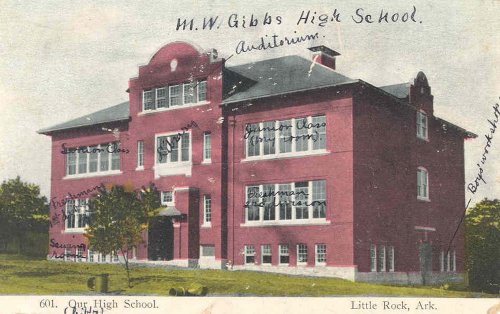

Postcard of M.W. Gibbs High School (date unknown). Individual rooms were labeled by sender. Top floor: auditorium. Second floor: senior class, library,

junior class (my room). First floor: freshmen (1st division),

freshmen (2nd division). Ground floor: sewing room, boys workshop.

Postcard courtesy of Ray Hanley.

picture sources: https://www.lrsd.org/Page/2964

PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT

There were six schools available to Black students – five of which were elementary schools. The one high school enrollment, M. W. Gibbs High School, located at the corner of 18th and Ringo, had outgrown the school’s capacity, and the building was slowly deteriorating. It eventually burned down, and the Black high school students needed somewhere to go since they could not attend Little Rock High School due to legal segregation laws. To uphold segregation efforts, a new school had to be built.

The Rosenwald Fund’s directors named the new school the Negro School for Industrial Arts, intending for it to only teach labor-force skills to the Black students. Black leaders were displeased with this and vied for the school’s curriculum to be inclusive of college-prep classes and academic topics. Aligned with the request of the Black leaders, the school’s name was changed to the Paul Laurence Dunbar High School to recognize the Black Poet Laureate, Paul Laurence Dunbar. (4)

The curriculum was established to fit Booker T. Washington’s (5) Tuskegee model's standards and used vocational education to emphasize economic advancement without challenging racial segregation or the disfranchisement of black voters. Washington used this method often to attract support and funding from Americans of any race who wanted educational equality in education but did not want to trigger hostile confrontation from white Americans. With the name and curriculum established, the physical building needed to be constructed.

Dr. Alfred K. Stern, director of the Rosenwald Fund, worked with R. C. Hall of the Little Rock schools and C. R. Hamilton, the superintendent of the Arkansas Negro Schools. They planned to build a 34-classroom structure that would accommodate multiple science laboratories, a vast library, a 1,000-seat auditorium, a cafeteria, laundry facilities, and seven industrial shops. Together with George H. Wittenberg and Lawson L. Delony of the Wittenberg & Delony Architects Firm in Little Rock, the architects of Little Rock High School, they designed, engineered, and constructed the building on a southeast-northwest axis. Designed with a functional style, the building would give occupants optimum usage of the space for its students’ vocational and academic programs.

There was an uncertainty of where the funding would come from to complete the school’s construction since the allocation for new schools, of any race, had just been used on Little Rock High School’s $1.5 million structure (today is known as Little Rock Central High School). The $400,000 construction project received $67,000 from the Rosenwald Fund and $30,000 from the General Education Board, with the remaining funded through local fundraising. The Black community and the Little Rock school board were equally pleased to receive the funding and encouragement to construct the new school.

There were six schools available to Black students – five of which were elementary schools. The one high school enrollment, M. W. Gibbs High School, located at the corner of 18th and Ringo, had outgrown the school’s capacity, and the building was slowly deteriorating. It eventually burned down, and the Black high school students needed somewhere to go since they could not attend Little Rock High School due to legal segregation laws. To uphold segregation efforts, a new school had to be built.

The Rosenwald Fund’s directors named the new school the Negro School for Industrial Arts, intending for it to only teach labor-force skills to the Black students. Black leaders were displeased with this and vied for the school’s curriculum to be inclusive of college-prep classes and academic topics. Aligned with the request of the Black leaders, the school’s name was changed to the Paul Laurence Dunbar High School to recognize the Black Poet Laureate, Paul Laurence Dunbar. (4)

The curriculum was established to fit Booker T. Washington’s (5) Tuskegee model's standards and used vocational education to emphasize economic advancement without challenging racial segregation or the disfranchisement of black voters. Washington used this method often to attract support and funding from Americans of any race who wanted educational equality in education but did not want to trigger hostile confrontation from white Americans. With the name and curriculum established, the physical building needed to be constructed.

Dr. Alfred K. Stern, director of the Rosenwald Fund, worked with R. C. Hall of the Little Rock schools and C. R. Hamilton, the superintendent of the Arkansas Negro Schools. They planned to build a 34-classroom structure that would accommodate multiple science laboratories, a vast library, a 1,000-seat auditorium, a cafeteria, laundry facilities, and seven industrial shops. Together with George H. Wittenberg and Lawson L. Delony of the Wittenberg & Delony Architects Firm in Little Rock, the architects of Little Rock High School, they designed, engineered, and constructed the building on a southeast-northwest axis. Designed with a functional style, the building would give occupants optimum usage of the space for its students’ vocational and academic programs.

There was an uncertainty of where the funding would come from to complete the school’s construction since the allocation for new schools, of any race, had just been used on Little Rock High School’s $1.5 million structure (today is known as Little Rock Central High School). The $400,000 construction project received $67,000 from the Rosenwald Fund and $30,000 from the General Education Board, with the remaining funded through local fundraising. The Black community and the Little Rock school board were equally pleased to receive the funding and encouragement to construct the new school.

OPEN THE DOORS

Dunbar Junior and Senior High School and Junior College was completed in 1929 and opened its doors to the Black students of Little Rock that same year. It accommodated seventh through twelve grade, plus a wing for its two-year junior college that trained teachers. The school offered Latin as a second language, algebra, carpentry, plumbing, sewing, and extracurricular activities such as athletics, music, drama, debate, and a chapter of the National Honor Society, and regularly included “Negro history” in the curriculum.

During the first year, seventy-four students were enrolled in its junior college. A dedication ceremony was held on April 14, 1930, around the same time the school’s first graduating high school class of fifty-eight students was preparing to complete the secondary school level. A total of 1,163 students had enrolled by fall 1930. The school thrived for the next 25 years, with hundreds of Black students attaining a formal, quality vocational or academic education on the junior high school, high school, and junior college level. It was one of two schools in the south that attained a junior college rating. It was also the only secondary school with a curriculum designed and accepted as admission to U.S. colleges and universities.

During the first year, seventy-four students were enrolled in its junior college. A dedication ceremony was held on April 14, 1930, around the same time the school’s first graduating high school class of fifty-eight students was preparing to complete the secondary school level. A total of 1,163 students had enrolled by fall 1930. The school thrived for the next 25 years, with hundreds of Black students attaining a formal, quality vocational or academic education on the junior high school, high school, and junior college level. It was one of two schools in the south that attained a junior college rating. It was also the only secondary school with a curriculum designed and accepted as admission to U.S. colleges and universities.

EXTRACURRICULARS

The school’s accessibility to state-of-the-art books, furniture, and equipment was minimal. When the school received anything, most of it was handed down from the all-white schools, and the campus did not have provisional space to accommodate all that the school was able to produce. This included a practice field and a gymnasium for gym class and extracurricular athletic activities. At certain points of the school’s existence, football players would have to walk sixteen blocks for practice and walk back to school to finish the day. To counter this deficit, Dunbar’s administrator made arrangements with the Mosaic Templar, Arkansas Baptist College, and the YMCA throughout the years that allowed the students to practice in their facilities.

In an oral interview made available in “The Road from Hell Is Paved with Little Rocks: Digitizing the History of Segregation and Integrations of Arkansas’s Educational System”, former Bobcat, Guy Covington, said:

“We would rather have our own, we’d rather had a good place to practice. …We had to practice on a vacant lot at 15th & Ringo. …right after they built a house on that lot, we moved to 15th & Cross. By that time, at 33rd & State, they started building an athletic field and we had to go out there to the club because they built two duplexes at 15th & Cross, so we had to practice where old Gibbs school had burned down and wasn’t nothing there but rocks... And that’s where we practiced until they got a contract agreement with Crump [Park] to practice out there. …we were right over near Ringo, and Crump was at 33rd & State. Now sometimes you would have a truck that would take you out there, but we had to get back to school, after practice was over, the best way we could – which was walk.”

Other popular extracurricular activities include the school newspaper, cheerleading, and pep squad, the Spanish Club, the homecoming and prom committees, the student yearbook, the debate team, student government, and band - the single largest activity at Dunbar. Despite this lack of uniforms, practicing facility, equipment, competitor options, and lack of recognition from the state and regional organization, Dunbar’s athletic teams were a popular feature of the school with stellar displays of athleticism.

The football, basketball, and track teams had a long-standing history of wins, with several local athletes’ names spreading throughout the city. The anticipated Dunbar High School Bobcats against Scipio Jones Dragons of North Little Rock Thanksgiving Day football game was always a big day for athletes. Unfortunately, little public press was given to Black sporting events as often as it should have been. As with its athletes, Dunbar students dealt with the same plights across the board. However, the school and the students’ commitment to perseverance and excellence was sound and unparalleled.

CLOSE THE DOORS

Unfortunately, the junior college program was abruptly discontinued by the board of trustees in May 1955 with no explanation. Simultaneously, evasive solutions for racial tensions were underway in the form of the Urban Renewal project. Dunbar High School held its last senior class graduation ceremony on May 27, 1955, at the Robinson Auditorium. Dunbar’s “High School” and “Junior College” components were terminated thereafter, and it became a junior high school in September 1955 while construction of Horace Mann commenced at 24th & McAlmont Street. Many students had to attend Dunbar until Horace Mann’s construction was completed on April 9, 1956.

NOTED BOBCATS

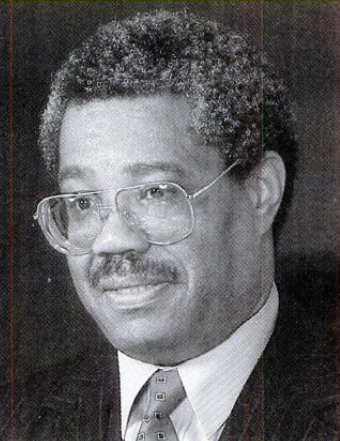

Former Bobcat star quarterback, Sidney Banks Williams, Jr., started as the Big Ten conference’s first black quarterback for the University of Wisconsin. He was also the subject of a college football civil rights dispute with Louisiana State University [LSU], who refused to let him play in their stadium. He is a 1954 Dunbar High School graduate.

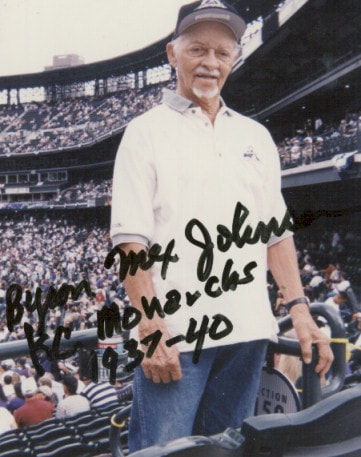

Although Dunbar did not offer baseball as an extracurricular activity, Byron “Mex” Emmerson Johnson ’s skills were recognized by a scout for the Kansas City Monarchs – a team of the Negro League Baseball – after he graduated from Dunbar High School. After graduating from Wiley College with an education degree, Johnson returned to Dunbar to teach biology and coach the football team. The Monarchs’ scout propositioned Johnson in 1936, but he turned the offer down focused on being a teacher. He was successfully propositioned a second time and played several seasons with the Monarchs making him a hometown star. He was also on the Satchel Paige All-Star Road team from 1939 to 1940.

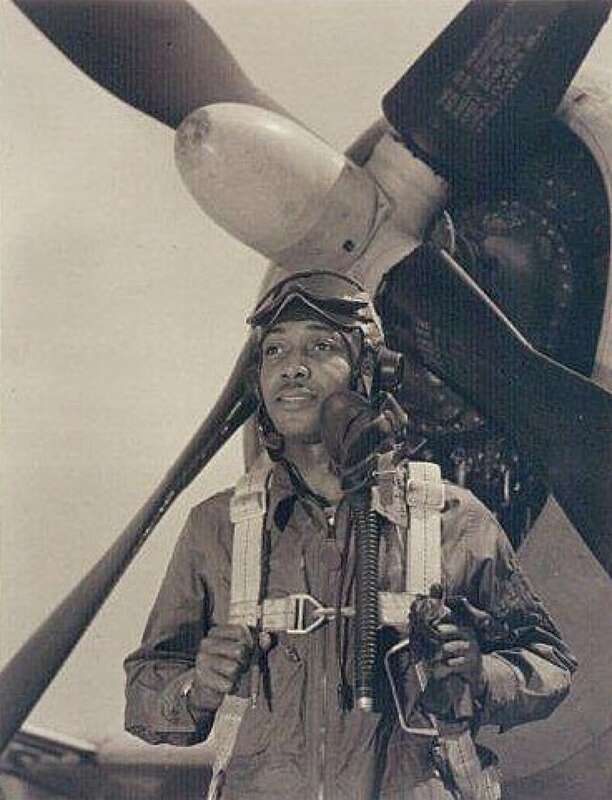

Another former Bobcat is Air Force Lt. Col. Woodrow “Woody” Crockett who would become a Tuskegee Airmen(6). His military career spans 30 years and includes 149 missions in World War II, 45 missions in Korea, and multiple honors and recognitions. He is a 1939 Dunbar High School graduate.

Educator Milton Crenshaw is a Black-American aviator and the first Arkansan to be completely trained as a civilian licensed pilot by the federal government. He was named the Primary Flight Instructor in 1942 at the Tuskegee Army Air Field in Tuskegee, Alabama, and trained many Tuskegee Airmen, including Air Force Lt. Col. Woodrow “Woody” Crockett. Crenshaw is considered to be the “Father of Black Aviation in Arkansas.” In 1947, he started an aviation course through Philander Smith College at the Little Rock Adams Field (today is known as the Little Rock National Airport) in the Central Flying Service building. Crenshaw taught this course for six years. He is a 1937 Dunbar High School graduate.

Retired educator Annie Mable McDaniel Abrams was instrumental in the campaign to rename Little Rock streets to honor Daisy Gatson Bates, Mayor Charles Bussey, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. She is also the force behind Little Rock’s first Martin Luther King, Jr. Day parade. Abrams is a 1950 Dunbar High School graduate and a 1952 Dunbar Junior College graduate.

Although Dunbar did not offer baseball as an extracurricular activity, Byron “Mex” Emmerson Johnson ’s skills were recognized by a scout for the Kansas City Monarchs – a team of the Negro League Baseball – after he graduated from Dunbar High School. After graduating from Wiley College with an education degree, Johnson returned to Dunbar to teach biology and coach the football team. The Monarchs’ scout propositioned Johnson in 1936, but he turned the offer down focused on being a teacher. He was successfully propositioned a second time and played several seasons with the Monarchs making him a hometown star. He was also on the Satchel Paige All-Star Road team from 1939 to 1940.

Another former Bobcat is Air Force Lt. Col. Woodrow “Woody” Crockett who would become a Tuskegee Airmen(6). His military career spans 30 years and includes 149 missions in World War II, 45 missions in Korea, and multiple honors and recognitions. He is a 1939 Dunbar High School graduate.

Educator Milton Crenshaw is a Black-American aviator and the first Arkansan to be completely trained as a civilian licensed pilot by the federal government. He was named the Primary Flight Instructor in 1942 at the Tuskegee Army Air Field in Tuskegee, Alabama, and trained many Tuskegee Airmen, including Air Force Lt. Col. Woodrow “Woody” Crockett. Crenshaw is considered to be the “Father of Black Aviation in Arkansas.” In 1947, he started an aviation course through Philander Smith College at the Little Rock Adams Field (today is known as the Little Rock National Airport) in the Central Flying Service building. Crenshaw taught this course for six years. He is a 1937 Dunbar High School graduate.

Retired educator Annie Mable McDaniel Abrams was instrumental in the campaign to rename Little Rock streets to honor Daisy Gatson Bates, Mayor Charles Bussey, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. She is also the force behind Little Rock’s first Martin Luther King, Jr. Day parade. Abrams is a 1950 Dunbar High School graduate and a 1952 Dunbar Junior College graduate.

PRESENT DAY

Today, the school is formally known as the Dunbar International Gifted and Talented Magnet Middle School and has been expanded and modified several times to accommodate its student body, including a practice field and a gymnasium. It is the only school designated explicitly for Gifted and Talented students in the Little Rock School District. It is one of the last remaining Black schools of the legal segregation era. On August 8, 1980, the Paul Laurence Dunbar Senior High School was added to the National Register of Historic Places list, thanks to the neighborhood residents and the National Dunbar Horace Mann Alumni Association.

Go to www.NDHMAA.com to learn how you can help sustain Dunbar’s physical and historic legacy.

Today, the school is formally known as the Dunbar International Gifted and Talented Magnet Middle School and has been expanded and modified several times to accommodate its student body, including a practice field and a gymnasium. It is the only school designated explicitly for Gifted and Talented students in the Little Rock School District. It is one of the last remaining Black schools of the legal segregation era. On August 8, 1980, the Paul Laurence Dunbar Senior High School was added to the National Register of Historic Places list, thanks to the neighborhood residents and the National Dunbar Horace Mann Alumni Association.

Go to www.NDHMAA.com to learn how you can help sustain Dunbar’s physical and historic legacy.