ARKANSAS BLACK HISTORY // Movement

Back to African Movement

Arkansas' Voyage to the Fatherland

by Dianna Donahue - Dec.01.2021

“Our Exodus movement is the uprising of poor but industrious and religious people, who desire to cultivate the land in Liberia and do good to the natives, promoting peace and Christian civilization.”

- Martin R. Delaney, South Carolina 1878

- Martin R. Delaney, South Carolina 1878

Black Americans began to return to their native land of Africa in 1820 – approximately 200 years after the transatlantic slave trade to Virginia began. Many of these brave souls were under the guidance of the American Colonization Society (A.C.S.), headquartered in Washington, D.C., and launched in 1816 by a group of white Americans. The organization arranged transportation and settlement for freed Blacks to make the voyage to Africa, specifically to the Republic of Liberia.

Liberia was a promise of land ownership and opportunity for freed Black people, which was not the promise of the South as a free Black human being. At the end of its seventy-eight years of operation, A.C.S. had aided 16,424 emigrants and 5,722 recaptured Africans to go back to Africa to reside in Liberia.

Arkansas’ portion of A.C.S.’s project began in 1877, subsided in 1882, but surged around the 1890s due to the racial violence and discrimination, low cotton prices, and sharecropping hardship – all backdrops for the first back-to-Africa expedition in America.

Liberia was a promise of land ownership and opportunity for freed Black people, which was not the promise of the South as a free Black human being. At the end of its seventy-eight years of operation, A.C.S. had aided 16,424 emigrants and 5,722 recaptured Africans to go back to Africa to reside in Liberia.

Arkansas’ portion of A.C.S.’s project began in 1877, subsided in 1882, but surged around the 1890s due to the racial violence and discrimination, low cotton prices, and sharecropping hardship – all backdrops for the first back-to-Africa expedition in America.

Approximately 13,000 free and redeemed slaves took advantage of the services that the American Colonization Society (A.C.S.) provided Black Americans. Many settled in Liberia before the Civil War when discriminatory practices were not as prevalent. However, after the Reconstruction Era ended in 1877, life in America went from bad to worse for Black human beings, and a new increased interest in African migration was created.

Black Arkansans regularly encountered racial discrimination at varying degrees and intensity as American history developed; however, those of the Mississippi Delta – more specifically, the Arkansas Delta – encountered greater. One of the more pressing racial matters in several counties of Arkansas’ Delta at the time was allowing Black people to vote. Phillips County was no exception to that. Although the county was predominately Black – 75% Black to be exact – its white residents actively enforced discrimination against Black people.

The 1876 presidential election polled a Republican majority in Phillips County; however, it only allowed ten of 15,000 Black residents to vote. In the 1878 elections, white Democrats took dramatic measures to keep Black Arkansans from voting, including positioning a cannon in front of the Phillips County’s primary polling place. Discriminatory occurrences and practices and the deteriorating status of Black Arkansans across Arkansas’ Delta motivated the development of the Back-to-Africa movement.

Black Arkansans regularly encountered racial discrimination at varying degrees and intensity as American history developed; however, those of the Mississippi Delta – more specifically, the Arkansas Delta – encountered greater. One of the more pressing racial matters in several counties of Arkansas’ Delta at the time was allowing Black people to vote. Phillips County was no exception to that. Although the county was predominately Black – 75% Black to be exact – its white residents actively enforced discrimination against Black people.

The 1876 presidential election polled a Republican majority in Phillips County; however, it only allowed ten of 15,000 Black residents to vote. In the 1878 elections, white Democrats took dramatic measures to keep Black Arkansans from voting, including positioning a cannon in front of the Phillips County’s primary polling place. Discriminatory occurrences and practices and the deteriorating status of Black Arkansans across Arkansas’ Delta motivated the development of the Back-to-Africa movement.

EXODUS

Arkansas’ exodus movement was the largest and strongest of all the Mississippi Delta’s counties through a formal organization of participants called the Liberian Exodus Arkansas Colony (L.E.A.C.). The organization held regular meetings hiding true intent from white neighbors. Its first convention was held in Helena of Phillips County on November 23, 1877, at the Third Baptist Church. People from Lee, St. Francis, Phillips, and Cross counties were in attendance, and they elected officers, formed a constitution, drew up a charter, and created over forty chapters.

L.E.A.C. received emigration applications from all seventy-five counties of Arkansas but only gave a particular interest to those that experienced the most political conflict and discrimination. Those counties were Woodruff, St. Francis, Lonoke, Jefferson, the Arkansas River Valley from Pulaski to Pope, and Conway County – where 1,500 Black Arkansans applied to emigrate because of the political violence. One of the leaders of the L.E.A.C. also took interest, but his were more specific to one county in particular.

Arkansas’ exodus movement was the largest and strongest of all the Mississippi Delta’s counties through a formal organization of participants called the Liberian Exodus Arkansas Colony (L.E.A.C.). The organization held regular meetings hiding true intent from white neighbors. Its first convention was held in Helena of Phillips County on November 23, 1877, at the Third Baptist Church. People from Lee, St. Francis, Phillips, and Cross counties were in attendance, and they elected officers, formed a constitution, drew up a charter, and created over forty chapters.

L.E.A.C. received emigration applications from all seventy-five counties of Arkansas but only gave a particular interest to those that experienced the most political conflict and discrimination. Those counties were Woodruff, St. Francis, Lonoke, Jefferson, the Arkansas River Valley from Pulaski to Pope, and Conway County – where 1,500 Black Arkansans applied to emigrate because of the political violence. One of the leaders of the L.E.A.C. also took interest, but his were more specific to one county in particular.

Anthony L. Stanford was a Black physician, African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) preacher, and the Republican state senator. He held his senate position from 1877 until 1880 over the fourteenth district in the Twenty-First and Twenty-Second General Assemblies, including Phillips and Lee counties. His particular interest in matters of the South and how Black people were being treated were centered around these counties. It is historically suggested that Stanford entered his campaign for the senate to use that seat to promote the back-to-Africa movement.

Once elected, Stanford distributed stationery of the House of Representatives to Black farmers in various counties. It is believed that he got the stationery from his friends who were Black members of the House using it to legitimize applications submitted by Black Arkansans seeking participation in the American Colonization Society’s back-to-Africa movement.

Stanford himself wrote a letter to the secretary-treasurer of the American Colonization Society stating:

Once elected, Stanford distributed stationery of the House of Representatives to Black farmers in various counties. It is believed that he got the stationery from his friends who were Black members of the House using it to legitimize applications submitted by Black Arkansans seeking participation in the American Colonization Society’s back-to-Africa movement.

Stanford himself wrote a letter to the secretary-treasurer of the American Colonization Society stating:

“The colored people of the South are extremely poor. Poverty is a word inadequate to describe the perilous condition of these people. And it seems impossible for them to extricate themselves. The white people of the South, many of them, labor to keep money out of the hands of these poor people in order to prevent their becoming able to leave the country. Some of the colored people, a few, have land and stock, but it is to them almost valueless as they can get no money for it. If there could be some plan adopted by which they could get ⅔ or even ½ of the value of what they possess, they could not only pay their own passage but assist others who are in more straitened circumstances.”

THE PROCESS

The L.E.A.C. leaders appointed commissioners to travel to Liberia to procure suitable land and arrange proper transportation for Black Arkansans to go to Liberia. Stanford C. H. Hicks was selected to make the trip, and they sailed to Liberia from New York aboard the Monrovia on January 2, 1878.

The two scouted the land for two months before returning to the United States, fully endorsing the project. Hicks stated that he believed Africa was where Black Americans needed to be because it was their homeland. He argued that it offered them more to gain than America and that he himself would make the migration with families from Forrest City, Mill Brook, Council Bend, and Wittsburg, Arkansas.

Stanford was in agreeance with Hicks, but was displeased that there were not more Black Arkansans there already. He reported to the A.C.S. that “…I find that Arkansas is not represented while colored people of almost every other state [have] been benefited.” He informed the A.C.S. that they should strongly consider Black Arkansans and that Arkansas’ inland position would make it economically difficult for its citizens to participate in the migration but that these would be ideal candidates for it. Stanford requested emigration assistance from the A.C.S., but with expressed caution for them to consider.

On June 9, 1878, Stanford wrote a letter to them from Philadelphia with reports stating that he believed Africa was, in fact, the natural home of the Negro and that they should be there. However, his concern was the mental state of people becoming aware of this opportunity. He did not want to make matters worse in the states or deter the progress being made in Africa and suggested that the A.C.S. be particular in their selection process:

The L.E.A.C. leaders appointed commissioners to travel to Liberia to procure suitable land and arrange proper transportation for Black Arkansans to go to Liberia. Stanford C. H. Hicks was selected to make the trip, and they sailed to Liberia from New York aboard the Monrovia on January 2, 1878.

The two scouted the land for two months before returning to the United States, fully endorsing the project. Hicks stated that he believed Africa was where Black Americans needed to be because it was their homeland. He argued that it offered them more to gain than America and that he himself would make the migration with families from Forrest City, Mill Brook, Council Bend, and Wittsburg, Arkansas.

Stanford was in agreeance with Hicks, but was displeased that there were not more Black Arkansans there already. He reported to the A.C.S. that “…I find that Arkansas is not represented while colored people of almost every other state [have] been benefited.” He informed the A.C.S. that they should strongly consider Black Arkansans and that Arkansas’ inland position would make it economically difficult for its citizens to participate in the migration but that these would be ideal candidates for it. Stanford requested emigration assistance from the A.C.S., but with expressed caution for them to consider.

On June 9, 1878, Stanford wrote a letter to them from Philadelphia with reports stating that he believed Africa was, in fact, the natural home of the Negro and that they should be there. However, his concern was the mental state of people becoming aware of this opportunity. He did not want to make matters worse in the states or deter the progress being made in Africa and suggested that the A.C.S. be particular in their selection process:

“Again, I do not think the colony so successfully planted in Liberia ought to be burdened with great numbers, at present, of the indolent, ignorant, and immoral class of American Negroes. I favor a gradual emigration of the more enterprising, hardworking, moral, and intelligent class. If some means could be adopted to aid this latter class as much as possible [,] I believe that such a course would not only prove a blessing to Africa but would also be the means of inducing the former class to make themselves efficient.”

By the time Stanford returned to Arkansas, he had realized that economics had changed again because of the drop in cotton price, and Black Arkansans were suffering and in no place to afford to migrate on their own. So he wrote a second letter to the A.C.S. on January 16, 1879, requesting funding assistance for the travel from Arkansas to New York and from New York to Liberia as people would not be able to make the movement otherwise.

Simultaneous to Stanford’s submission of requests to the A.C.S., white people were becoming aware of the back-to-Africa movement and wanted to end the effort. A Black Presbyterian minister and schoolteacher from North Creek in Phillips County named B. K. McKeevers stated that “The Kuklus [Ku Klux Klan] has begun to talk to Negroes out here and whip them about a week ago [;] they taken out one C. J. Thomas (Clerk of co. No. 16 Liberia Exodus Ark Colony). After giving him two heavy blows over the head with a pistol he got away. Dear Sir, I hope you will do all you can for me as I shall continue to seek an asylum from this segnedation [segregation] . . . may long live the Colonization Society for this great favor to the anglo African.”

Stanford was unable to do anything while the A.C.S. made its decision, so he went on a lecture circuit to raise money for the movement. Then he was notified that A.C.S. members were advocating for migration to the American West instead of Africa, and Stanford opposed. Liberia was the only option. He himself requested assistance for his own participation in the movement as he was nearly penniless, yet better than most Black Arkansans.

The 1880s brought improved conditions for Black people in the Delta politically as Black Republicans won back authority in the 1882 elections. Several Black officials were elected to positions that they would hold for the rest of the decade. Word spread throughout the Delta of the potentials for Black prosperity. Hundreds of Black people, from South Carolina in particular, migrated to Arkansas’ Delta to escape their own opposition. For many, it was one step closer to reaching African soil.

Simultaneous to Stanford’s submission of requests to the A.C.S., white people were becoming aware of the back-to-Africa movement and wanted to end the effort. A Black Presbyterian minister and schoolteacher from North Creek in Phillips County named B. K. McKeevers stated that “The Kuklus [Ku Klux Klan] has begun to talk to Negroes out here and whip them about a week ago [;] they taken out one C. J. Thomas (Clerk of co. No. 16 Liberia Exodus Ark Colony). After giving him two heavy blows over the head with a pistol he got away. Dear Sir, I hope you will do all you can for me as I shall continue to seek an asylum from this segnedation [segregation] . . . may long live the Colonization Society for this great favor to the anglo African.”

Stanford was unable to do anything while the A.C.S. made its decision, so he went on a lecture circuit to raise money for the movement. Then he was notified that A.C.S. members were advocating for migration to the American West instead of Africa, and Stanford opposed. Liberia was the only option. He himself requested assistance for his own participation in the movement as he was nearly penniless, yet better than most Black Arkansans.

The 1880s brought improved conditions for Black people in the Delta politically as Black Republicans won back authority in the 1882 elections. Several Black officials were elected to positions that they would hold for the rest of the decade. Word spread throughout the Delta of the potentials for Black prosperity. Hundreds of Black people, from South Carolina in particular, migrated to Arkansas’ Delta to escape their own opposition. For many, it was one step closer to reaching African soil.

FATHERLAND BOUND

With the organization’s help, Stanford led twenty-three Phillips County residents to New York in preparation for Liberia in 1879. The route included passing through Pennsylvania, where they lived for several months with aid donated by the A.C.S.’s Pennsylvania chapter in the amount of $4,000. Expecting a similar experience in New York, the emigrants arrived in anything but that.

Thirty-four men, thirty-two women, and thirty children were forced to live in a filthy apartment at No. 118 Thirty-Seventh Street in Denham Court. The location was destitute of resources, including food, shelter, and water, and the emigrates became known as the “Arkansas Refugees” because of the conditions they were forced to live in. Eventually, more immigrants arrived, and conditions worsened, including death. Stanford and others took action to get the refugees’ assistance to survive until it was time to travel to Liberia.

In April 1880, a prominent Black militant leader named Reverend Henry Highland Garnet of the Shiloh Presbyterian Church spoke to a news reporter about the conditions of the refugees, stating:

With the organization’s help, Stanford led twenty-three Phillips County residents to New York in preparation for Liberia in 1879. The route included passing through Pennsylvania, where they lived for several months with aid donated by the A.C.S.’s Pennsylvania chapter in the amount of $4,000. Expecting a similar experience in New York, the emigrants arrived in anything but that.

Thirty-four men, thirty-two women, and thirty children were forced to live in a filthy apartment at No. 118 Thirty-Seventh Street in Denham Court. The location was destitute of resources, including food, shelter, and water, and the emigrates became known as the “Arkansas Refugees” because of the conditions they were forced to live in. Eventually, more immigrants arrived, and conditions worsened, including death. Stanford and others took action to get the refugees’ assistance to survive until it was time to travel to Liberia.

In April 1880, a prominent Black militant leader named Reverend Henry Highland Garnet of the Shiloh Presbyterian Church spoke to a news reporter about the conditions of the refugees, stating:

“These people came here on their own accord. They left Arkansas to avoid oppression. Except that they were not held in bondage, their condition was worse than when slavery existed. Colored men there were hired by the year. They are paid no money until the twelve months expire, meanwhile purchasing the necessities of life from their employers, who charge three or four times more than the market rates. In this way the laborers are brought into debt, and under the law of the state, they cannot leave an employer’s service while in arrears to him. To avoid this [a] colony was formed to settle in Liberia.”

The subsequent headlines of two consecutive columns in the New York Evening News newspaper read:

“WRETCHED REFUGEES-EMIGRANTS FOR LIBERIA ON THE VERGE OF STARVATION” and “WRETCHED CONDITION OF THE ARKANSAS REFUGEES. THE DEATHTOLL INCREASING.”

This sparked a public interest to aid the refugees, inclusive and beyond New York. The A.C.S. underwrote the newspaper by circulating advertisements about the destitution that the refugees were experiencing, and the contributions started to come in, such as clothing, baskets, food, and money.

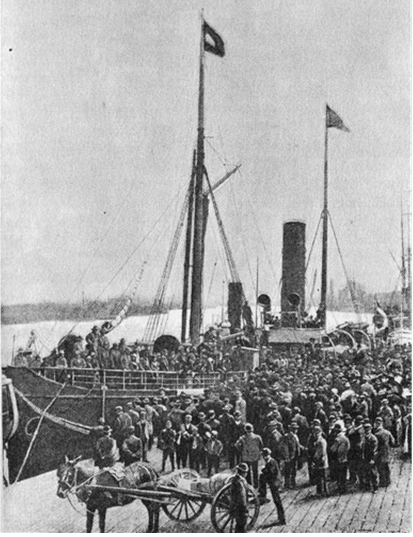

One hundred and thirty-six Arkansas emigrants left America in May 1880 – on May 22 on a ship headed to Liberia and on May 29 on a ship heading to Monrovia. Unfortunately, some refugees could not afford to pay for the second half of the expedition and were delayed departure until the fall of that year. However, the Arkansas Refugees comprised the largest group to make the voyage: seventy-six were twelve years of age and above; forty-nine were between eleven and two years of age, and eleven were only two years old. Of those people were twenty-five good standing Baptist and Methodist churchgoers, twenty-three farmers, two coppers, two teachers, two ministers, one blacksmith, and one brick mason.

One hundred and thirty-six Arkansas emigrants left America in May 1880 – on May 22 on a ship headed to Liberia and on May 29 on a ship heading to Monrovia. Unfortunately, some refugees could not afford to pay for the second half of the expedition and were delayed departure until the fall of that year. However, the Arkansas Refugees comprised the largest group to make the voyage: seventy-six were twelve years of age and above; forty-nine were between eleven and two years of age, and eleven were only two years old. Of those people were twenty-five good standing Baptist and Methodist churchgoers, twenty-three farmers, two coppers, two teachers, two ministers, one blacksmith, and one brick mason.

AFRICAN PROMISELAND

The second ship to depart New York arrived in Monrovia, Africa, thirty-two days later. Upon arrival, the Republic of Liberia gave each Arkansas family twenty-five acres of free land. Most families combined their land into two communities several miles away from Monrovia, Liberia’s capital, and named them Brewerville and Johnsonville. The second ship’s passengers’ new home was Brewerville, located on the St. Paul River; however, both locations offered the fullness of freedoms that many had only dreamed of. Unfortunately, Stanford died three years after reaching Africa. Nevertheless, he accomplished success and status in his short time becoming the Judge of the Court of Quarter Sessions and Common Pleas. He was eulogized as a man of “excellent ability” and “rare qualities.”

The Arkansas emigrants became acclimated to their new home, but it was not without hardships. Liberia is located in one of Africa’s most tropical wetlands and was once a breeding ground for diseases, such as malaria. As Arkansans prepared to clear land for farming and build homes, many took ill with the disease, and development progress was impacted. Moreover, the progress made was countered by adjusting how to grow and harvest coffee, the profitable crop of the land – a big difference from cotton crops in the South.

The second ship to depart New York arrived in Monrovia, Africa, thirty-two days later. Upon arrival, the Republic of Liberia gave each Arkansas family twenty-five acres of free land. Most families combined their land into two communities several miles away from Monrovia, Liberia’s capital, and named them Brewerville and Johnsonville. The second ship’s passengers’ new home was Brewerville, located on the St. Paul River; however, both locations offered the fullness of freedoms that many had only dreamed of. Unfortunately, Stanford died three years after reaching Africa. Nevertheless, he accomplished success and status in his short time becoming the Judge of the Court of Quarter Sessions and Common Pleas. He was eulogized as a man of “excellent ability” and “rare qualities.”

The Arkansas emigrants became acclimated to their new home, but it was not without hardships. Liberia is located in one of Africa’s most tropical wetlands and was once a breeding ground for diseases, such as malaria. As Arkansans prepared to clear land for farming and build homes, many took ill with the disease, and development progress was impacted. Moreover, the progress made was countered by adjusting how to grow and harvest coffee, the profitable crop of the land – a big difference from cotton crops in the South.

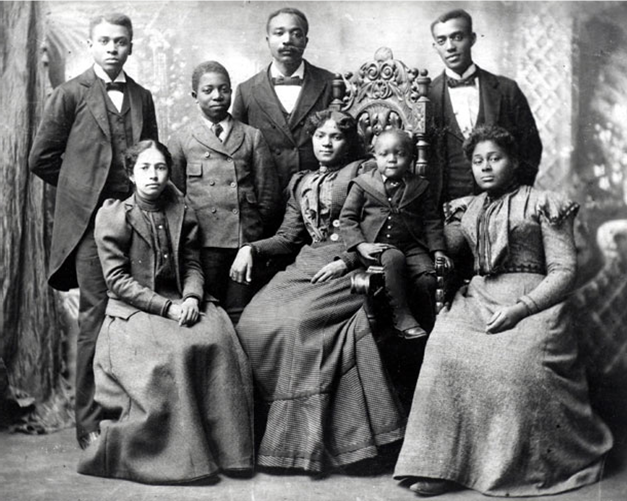

Victoria David Tolbert, former first lady of Liberia

Victoria David Tolbert, former first lady of Liberia

Unfortunately, just as the emigrants’ coffee trees began producing, coffee prices dropped drastically with the uprise of coffee production in Brazil in the late 1890s. Nevertheless, Arkansas Refugees developed their new home with houses, farms, schools, and churches and introduced technology, culture, and democratic models to Liberians.

Generationally, Black Arkansans prospered in Liberia. Some wanted to go back to Arkansas, but many stayed and made their new home work and began to thrive in status and economics. A noted example of this is Isaac David. His family left Little Rock in 1891 during the Back-to-Africa movement when he was five years old. He stayed there, eventually starting a family, and his daughter, Victoria David Tolbert, would become the first lady of Liberia.

Generationally, Black Arkansans prospered in Liberia. Some wanted to go back to Arkansas, but many stayed and made their new home work and began to thrive in status and economics. A noted example of this is Isaac David. His family left Little Rock in 1891 during the Back-to-Africa movement when he was five years old. He stayed there, eventually starting a family, and his daughter, Victoria David Tolbert, would become the first lady of Liberia.

CHANGING OF THE GUARDS

Violent political and racial occurrences returned at the beginning of the 1890s when the Democratic party was opposed by a biracial alliance of rural poor people, the agrarian populist, and the Republican party. The Democrat party again resorted to dramatic measures to ensure their state legislature control, including fraud and terrorist actions that were far greater than those used in years prior. With this control, they were able to pass laws purposed to disenfranchise Black and poor white voters in 1891, and Jim Crow segregation laws were created with hundreds of America’s most heinous lynchings happening right in Arkansas. The pressure to get to Liberia heightened and Black Arkansans became desperate to escape.

In 1892, thirty-four Black, Woodruff County Arkansans sold all of their possessions to get to New York to request the assistance of the A.C.S. but were denied. Unable to afford transportation back home, there was another refugee crisis for the A.C.S. to handle. This time, it caused the organization to cease operations completely, just as Arkansas’ demand for it skyrocketed.

Violent political and racial occurrences returned at the beginning of the 1890s when the Democratic party was opposed by a biracial alliance of rural poor people, the agrarian populist, and the Republican party. The Democrat party again resorted to dramatic measures to ensure their state legislature control, including fraud and terrorist actions that were far greater than those used in years prior. With this control, they were able to pass laws purposed to disenfranchise Black and poor white voters in 1891, and Jim Crow segregation laws were created with hundreds of America’s most heinous lynchings happening right in Arkansas. The pressure to get to Liberia heightened and Black Arkansans became desperate to escape.

In 1892, thirty-four Black, Woodruff County Arkansans sold all of their possessions to get to New York to request the assistance of the A.C.S. but were denied. Unable to afford transportation back home, there was another refugee crisis for the A.C.S. to handle. This time, it caused the organization to cease operations completely, just as Arkansas’ demand for it skyrocketed.

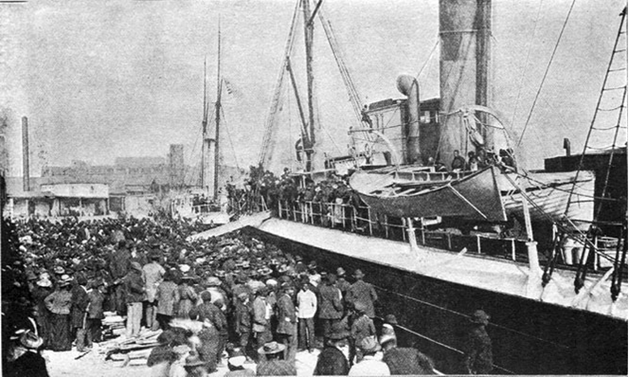

White businessmen in Birmingham, Alabama, decided to create a company to continue the services of the A.C.S. Under their effort, over 200 Black Arkansans from St. Francis, Lonoke, and Jefferson counties were transported to Liberia over the courses of three trips between 1894 through 1896. Black Arkansans also traveled commercially by steamers leaving from New York ports in Europe as interest turned into missionary work, representing nearly a quarter of Africa’s known Black missionaries that decade.

Today, Black people have more liberties and freedoms than our ancestors; however, they regularly experience their residuals. Many have moved to Africa as permanent citizens of the country or to have a glimpse of genuine connection to the land of their ancestors. The racial tensions of 2020 created a surge in interest and action, and African countries, such as Ghana welcomed the transition enthusiastically.

Today, Black people have more liberties and freedoms than our ancestors; however, they regularly experience their residuals. Many have moved to Africa as permanent citizens of the country or to have a glimpse of genuine connection to the land of their ancestors. The racial tensions of 2020 created a surge in interest and action, and African countries, such as Ghana welcomed the transition enthusiastically.

“[Liberia is] the colored man’s home, the only place on earth where they have equal rights…there are no white men here to give orders; and when you go in your house, there is no one to stand out and call you to the door and shoot you when you come out.

We have no foreman over us; we are our own boss. We work when we want to, and sit down when we choose and eat when we get ready.”

- Williams Rogers, an Arkansas emigrant from Morrilton